|

All but one of Guiseppe Verdi's masterworks are operas.  This poses a problem for those of us who aren't opera buffs. Fortunately, though, that one exception is his stunning Requiem, into which he poured the same vibrant emotion that thrills opera fans, but without the trite plots, simplistic characters and dull narrative stretches that tend to alienate others. Indeed, more than a few critics have hailed the Requiem as Verdi's finest opera. This poses a problem for those of us who aren't opera buffs. Fortunately, though, that one exception is his stunning Requiem, into which he poured the same vibrant emotion that thrills opera fans, but without the trite plots, simplistic characters and dull narrative stretches that tend to alienate others. Indeed, more than a few critics have hailed the Requiem as Verdi's finest opera.

Verdi's inspiration was neither religious, egotistical nor fiscal.  Rather, his gesture was one of national pride. He considered the opera composer Gioacchino Rossini one of the two greatest Italian artists of his time. Four days after Rossini's death on November 13, 1868, Verdi wrote his publisher Ricordi to propose a requiem mass to be given one year later in Rossini's heartland of Bologna. Each of the twelve sections was to be written by an Italian composer, so that the result would compensate for any lack of unity with a variety of universal veneration. Verdi himself would supply the concluding section. There was to be "no foreign hand, nor hand foreign to art, no matter how powerful, to help us." To avoid petty vanity, all composers and performers were to contribute their services. To avoid exploitation, the score was to be sealed in the city archives and presented only on subsequent anniversaries of Rossini's death. While all the assignments were completed in ample time, the performance never materialized, the organizing committee was disbanded, Verdi refused to allow publication or performance of his portion, and in 1873 his score was returned. He soon found another appropriate use for it. Rather, his gesture was one of national pride. He considered the opera composer Gioacchino Rossini one of the two greatest Italian artists of his time. Four days after Rossini's death on November 13, 1868, Verdi wrote his publisher Ricordi to propose a requiem mass to be given one year later in Rossini's heartland of Bologna. Each of the twelve sections was to be written by an Italian composer, so that the result would compensate for any lack of unity with a variety of universal veneration. Verdi himself would supply the concluding section. There was to be "no foreign hand, nor hand foreign to art, no matter how powerful, to help us." To avoid petty vanity, all composers and performers were to contribute their services. To avoid exploitation, the score was to be sealed in the city archives and presented only on subsequent anniversaries of Rossini's death. While all the assignments were completed in ample time, the performance never materialized, the organizing committee was disbanded, Verdi refused to allow publication or performance of his portion, and in 1873 his score was returned. He soon found another appropriate use for it.

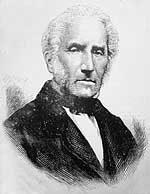

Verdi's other idol was Alessandro Manzoni. Although Manzoni had written only a single novel, I promessi sposi ("The Betrothed"), it was so popular that the author became the leading Italian literary figure of the century. A sprawling historical tale of peasant lovers buffeted by and triumphing over the repression of society, religion and injustice, it emerged as the driving literary force of the Risorgimento movement for Italian unification. Originally published in 1827, in 1840 Manzoni rewrote it in Tuscan, which he considered the pure indigenous Italian language. William Manning notes that beneath its plot and characters, it served as "a kind of stylebook of the language of a country which though politically united was linguistically chaotic."

Alessandro Manzoni

(1785-1873) |

As a teenager, Verdi had read the book following its initial publication and came to view it as serving two complementary and ideal uses of art for social ends - not only did it transcend politics to rally people by appealing to their collective roots, but its popularity served as a cultural emissary to attract the world's attention and admiration. When he finally met Manzoni in 1868, Verdi revered him as a saint.

Although Manzoni's death in his 89th year was hardly unexpected, Verdi was deeply grieved. The next day he wrote to his publisher Ricordi that although he wouldn't attend the funeral, "I will come in a little while to visit his tomb, alone and without being seen, and perhaps (after further meditation and after having gauged my strength) to suggest something to honor his memory." The next week Verdi made his pilgrimage, condemned the many published tributes as superficial and resolved to write a requiem, but this time without the political snags and bickering that had thwarted his Rossini project. His proposal – to write the entire mass himself if Milan would fund its first performance. Despite opposition from the city council which already had funded a lavish funeral, the mayor accepted, the San Marco church was selected as the venue for its acoustics, the convention of using a priest to recite liturgy between musical numbers was bypassed, and the Archbishop gave special permission to use female performers on condition that they be veiled, dressed in black and hidden behind a grating. Verdi's project was officially titled Messa da Requiem per l'anniversario della morte de Manzoni, 22 Maggio 1874 ("Requiem mass for the anniversary of Manzoni's death, May 22, 1874").

The resulting work was indeed as dramatic as any Verdi opera. George Marek calls it "a prayer for peace by a man who had devoted his music to conflict." As George Martin has noted, it is suffused with Verdi's personal doubts as to the efficacy of prayer, a concern perhaps heightened by his advancing age and fear of what lay ahead. Indeed, the Requiem's very strength lies in its exploration of Verdi's ambivalent views toward religion, given reign through the unparalleled sense of theatre he had developed.

Guiseppi Verdi

(1813 – 1901) |

As Cecilia Porter notes, death is a complex character in the Requiem, playing multiple roles – an object of terror, a comforter, an emancipator – fully reflecting Verdi's penchant toward intensely human drama rather than a staid presentation of liturgical dogma or an intellectual effort at theological exploration (a task which Verdi, a very plain man, could never have abided). It's indeed ironic that from this simple man, with no pretension of philosophical insight, arose a work that presents a far more potent sense of sophisticated (and quite modern) theology than the religious works of most of his predecessors.

Martin further notes that since a requiem is an assortment of responses and prayers without a rigidly prescribed text, and since Verdi never intended his work to be sung as part of an actual church service, he could select and emphasize portions that ran the gamut of human experience, ranging from sadness to joy, simplicity to majesty, reflection to apocalypse. As a man of the theatre, Verdi chose to fashion these disparate elements into a drama from which solos would emerge as true individuals, rather than as offshoots of the massed choir. Indeed, his use of solo voices is daringly intricate – not the decorative figures of Haydn, nor the schematic personas in Bach cantatas, but multi-faceted roles that often complicate the texture to subtly question the apparent meaning of the wording presented by the underlying choral forces. The soprano, in particular, seems to voice Verdi's own ambivalent skepticism, adding emotional intensity at odds with the faith-based text and affording a wide latitude for interpretation – indeed. in their respective recordings, Elizabeth Schwartzkopf whispers the final "libera me," Galina Vishnevskaya nearly chokes on those words, and Herva Nelli snarls the passage as a stern defiant demand.

Of Verdi's primary models, Mozart had couched his Requiem in classical order, Cherubini had dwelled on the Offeratorium's hope for deliverance and Berlioz had deployed his massive performing forces only in the intensely powerful and vivid Dies irae, Lachrymosa and Sanctus sections, projecting throughout the remaining movements a somewhat meandering overall sense of peace and contentment amid ingenious sonic effects (including quadraphonic placement of voices and brass). In contrast, Verdi's score is intensely melodic, tightly focused and bristles throughout with surging passion and challenging discomfort.

Why did Verdi choose a mass, rather than an oratorio of Manzoni's own words, to honor his hero? After all, although severely moral, Verdi was anti-clerical and an agnostic; his wife considered him an atheist and recalled that he would laugh and call her mad when she spoke of religion. Martin suggests historical and practical motivations – masses had been used by Cherubini and Rossini to honor departed public figures and thus a work in that genre was more likely to be welcomed elsewhere. Besides, Verdi already had a large emotional investment in his contribution to the aborted Rossini venture. Perhaps on a more personal level, Verdi found an outlet in the varied text of the requiem to explore his own ambivalent faith through his inherent sense of drama.

The tone is set at the very opening, in which soloists challenge the calm choral serenity of the Requiem aeterna with emphatic individual entreaties.  The ensuing Sequenz, whose 11 sections occupy nearly half the work's total length, is suffused with human drama that explores a wide range of emotion while preserving an overall sense of musical continuity. Based on a rhymed 13th century Latin poem, it begins with a heaven-storming eruption of the Dies irae ("Day of Wrath"), intensified by syncopated thwacks on a huge bass drum, and proceeds through the sun-blasted brass and tympani of Tuba mirim; a chilling bass solo drained of even a shred of melody (Mors stupendit); the mezzo's dire warning of the book in which deeds are recorded (Liber scriptus); a desperate quest for a path to salvation (Quid sum miser) in which, in Michael Steinberg's phrase, the soloists seem to cling to each other for support at the height of their perplexed fears; a full choral promise of divine judgment that sounds far more imperious and intimidating than inviting and just (Rex tremendae); fervent yet tender arias of a sinner's confession and a plea for absolution (Recordare and Ingemisco); an abject appeal for contrition (Confutatis); and then an abbreviated return of the terrifying Dies irae that sweeps all of these aside in a wave of utter fear. Finally, there remains only a heart-rending simple plea for mercy (Lacrymosa). The ensuing Sequenz, whose 11 sections occupy nearly half the work's total length, is suffused with human drama that explores a wide range of emotion while preserving an overall sense of musical continuity. Based on a rhymed 13th century Latin poem, it begins with a heaven-storming eruption of the Dies irae ("Day of Wrath"), intensified by syncopated thwacks on a huge bass drum, and proceeds through the sun-blasted brass and tympani of Tuba mirim; a chilling bass solo drained of even a shred of melody (Mors stupendit); the mezzo's dire warning of the book in which deeds are recorded (Liber scriptus); a desperate quest for a path to salvation (Quid sum miser) in which, in Michael Steinberg's phrase, the soloists seem to cling to each other for support at the height of their perplexed fears; a full choral promise of divine judgment that sounds far more imperious and intimidating than inviting and just (Rex tremendae); fervent yet tender arias of a sinner's confession and a plea for absolution (Recordare and Ingemisco); an abject appeal for contrition (Confutatis); and then an abbreviated return of the terrifying Dies irae that sweeps all of these aside in a wave of utter fear. Finally, there remains only a heart-rending simple plea for mercy (Lacrymosa).

The ensuing major sections comprise an Offeratory in which the solo quartet sweetly but ardently asks for deliverance, a swift and giddy Sanctus in which the choir is stereophonically divided to trade leaping phrases of unabashed joyous praise, and a shimmering a capella prayer for eternal rest featuring the soprano and mezzo soloists in tight parallel motion (Agnus dei). But then the respite is broken and the purity and affirmation of these longings are darkened in the Lux aeterna by an ominous challenge of deep brass figures and by increasing tension between orchestra and chorus, creating a division between text and presentation, highlighted by the soprano's attempts to soar toward the light, at first boosted by feathery flute and violin, but then weighted down by the rest of the instruments.

While Mozart, Cherubini and Berlioz had completed their requiems with the peaceful supplications of an Agnus dei or Lux aeterna, Verdi added a further section to conclude on a note not of consolation but discomfiting trepidation. Indeed, the Libera me not only serves as the culmination of the entire work but as its summation and emotional core, as if, having dutifully respected the traditional components of a requiem mass, Verdi at last steps out to have a final, deeply personal say.  While the movement mostly follows the version he had prepared for the Rossini mass, Verdi enhances the first portion of the Dies irae outburst with a more intense orchestral role, darkens the texture, and shifts emphasis from the universality of the chorus to the personal plea of the solo soprano. While the movement mostly follows the version he had prepared for the Rossini mass, Verdi enhances the first portion of the Dies irae outburst with a more intense orchestral role, darkens the texture, and shifts emphasis from the universality of the chorus to the personal plea of the solo soprano.

The structure of his Libera me is one of disconcerting clashes of styles and a succession of moods that dispels any comfort the text might suggest. It begins in the naïve pure faith of hushed monotone Gregorian chant, soon challenged by trembling fear of the soprano's premonition of the day of reckoning. The tranquility is shattered by a reprise of the uproar of the Dies Irae outburst from the second movement, followed by a reflection of the Requiem aeterna that opened the work, but this time, rather than setting an initial reverential mood and reference point, it barely dispels the preceding turmoil; indeed, its temporizing aura of universal order is soon challenged by the soprano, this time embellishing the soothing choral lines with a reminder of the skeptical human dimension. Then, after she turns fearful once again, there erupts a stern fugue, that most venerable, staid and intellectual of musical forms, suggesting a final effort to restore order and revert to historical precedent, but in this context it seems more an insistent demand than an appealing supplication. Soon, its universal abstraction, too, ultimately cedes to the increasingly desperate human quest of the lone soprano. Indeed, it seems that Verdi, like Jesus, has humanized the relationship between mankind and deity concerning death, the one mystery of life that we all must confront regardless of social rank or religious outlook.

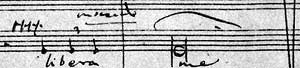

After a final climax that utterly exhausts the chorus, the soprano offers a line of chant in a nearly conversational tone (marked in the score "senza misura" – "without strict time") and then, as softly as possible (marked "pppp") at the very bottom of her range (middle C) and utterly drained of feeling (the score specifies "morendo" – "dying") with final breaths barely manages to growl two final pleas of "libera me" as if, having tried all the standard approaches to prayer, she is left stripped of any armor religion might provide to confront the worst fear of all for a culture steeped in faith – that at the very end of life's struggle there is no salvation at all but only eternal silence. And so Verdi's Requiem ends in a gesture that's musically and philosophically both thoroughly modern in its theology and utterly devastating in its emotional impact.

The conclusion in Verdi's autograph |

Even before its first performance, the Requiem met critical resistance. Hans von Bulow disparaged it as "oper im Kirchengewande" ("opera in ecclesiastical dress") and others denounced its cheapening of religion with theatrical contrivances. Critics ever since have debated the nature of the work. Its juxtaposition of solo voices and chorus, extreme sensitivity to the text, and outright drama have marked it as operatic, and indeed Verdi cast the two female solos with opera stars who had created the leads in his Aida four years earlier and rejected a tenor who wasn't spontaneous enough. Yet, its counterpoint and repetition, avoidance of casting soloists as specific characters, and massive sonic structures suggest theatre, in the service of which Verdi demanded that the orchestra play with "verve and fire" and used choruses ranging from 120 singers for the premiere to 1,200 on tour at London's Albert Hall. All the while, its respectful treatment of the text is palpably religious – Eduard Hanslick quipped: "When a female singer appeals to Jesus, she shouldn't sound as if she were pining for her lover." Verdi hedged, saying only that he didn't want it sung as opera or theatre: "There are questions of expression and character that are not so easy."

But, as Robert Jacobson noted, these are needless distinctions – while Northern Europe tended to treat matters of faith with austere awe, Italy and Spain had a long tradition of bringing religion and drama under one roof – quite literally, as their resplendent Baroque churches fused art, architecture and ritual into a dazzling spectacle that overwhelmed worshippers. As Verdi said, "The interiors of churches need not be dimly lit."

Verdi conducting his Requiem in Milan

– an orchestra of frenzied skeletons! |

Hanslick rebutted Bulow by noting that no music since Gregorian chant is "pure" and that Verdi was merely talking to God in his own language, reflecting the emotional range of the composer's own people. Verdi's wife Guiseppina summed it up well: "I would have disowned a Mass by Verdi that had been made following Model A, B or C. … A man like Verdi must write like Verdi." Marek has likened the Requiem to Michelangelo's Last Judgment, which also had been rebuked for its raw emotion that upset expectations of spirituality – both works place far greater emphasis on terror than comfort, perhaps reflecting Verdi's view of Italy adrift without the cultural anchor Manzoni had provided.

The premiere in San Marco was such a success that three more performances were held at Milan's legendary La Scala opera house, complete with an intermission after the Sequenz and numerous encores. With that, Francis Tovey notes: "The Mass had arrived at its real home, … where the audience, now unrestrained by ecclesiastical conventions, were able to give vent to their enthusiasm in all its typically Italian exuberance." Indeed, unlike his plans for the Rossini project, Verdi had no intention of caching the score, to be aired only for rare solemn civic commemorations. Rather, Verdi wanted his work to complement Manzoni's own achievement as a proud emissary for displaying Italian culture to the world, and personally took it on tour to Paris, New York, London and Vienna.

In urging a retired opera star to participate in the premiere without pay, Verdi, in all humility, predicted that his Requiem would be "something that will make history, not because of the nature of the music, but because of the man to whom it is dedicated." Yet, while Manzoni is barely remembered nowadays, the fresh, direct radiance of his Requiem endures.

|

As compiled by W. G. Busse's Verdi's Disco website, through January 2005 there have been 135 recordings of the Verdi Requiem. In sorting through them, a key gauge is that of timing. Noting that Verdi conducted with limited elasticity and adhered to a basic tempo, David Rosen estimated an appropriate pace by calculating the duration of each section based on its length and Verdi's metronome markings, and came up with a total timing of about 70 minutes. Yet that may be of purely academic interest. Arturo Toscanini recalled that when preparing Verdi's final work, the 1898 Te Deum, for its Italian premiere, the composer approved his instinctive slowing down at one spot, even though there was no direction to do so in the score. Verdi explained that had he so notated the effect, conductors would be apt to exaggerate, while true musicians would feel it naturally and play it properly.

Verdi knew his conductors well. A touchstone is at measure 44 of the Dies irae – although Verdi marked the final notes of a descending bass line as stent. un poco ("slightly drawn out"), few conductors resist the tendency to inflate the gesture and grind the pace nearly to a halt. Indeed, despite Verdi's express tempo indications, Toscanini's own three recorded performances range from 77 to 88 minutes. (The German score specifies a timing of 97 minutes but cites no authority and so could just be an editor's whim.) Thus, any notion of an authentic pacing is illusory.

Of the many notable recordings, I especially enjoy the following (listed by conductor, ensemble, year, length and current CD availability):

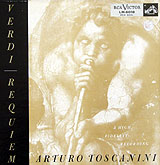

- Arturo Toscanini – BBC, London, 1938 (88 minutes, Testament CD); NBC, New York, 1940 (84 minutes, Music & Arts CD); NBC, New York, 1951 (77 minutes, BMG CD) — Toscanini brings us closer than any other conductor to Verdi,

stemming from his personal association with the composer which began when he played cello under Verdi's baton at the premiere of Aida – and to the Requiem itself, which he led in 1902 to mark the first anniversary of Verdi's death, and for a final time in 1951 to commemorate the 50th. All of his three recordings are magnificent and presumably reflect Verdi's own approach of constant pacing, minimal inflection and telling detail. Yet, at least with respect to their vastly different pacing, they defy any attempt at a monolithic guide for idiomatic interpretation. The 1951 recording of a Carnegie Hall concert is the most widely-circulated, yet Toscanini reportedly was ashamed and refused to release it until rehearsal segments were spliced in. Abetted by the tight pace, there's a palpable tension, with nearly every phrase tightly-wound, and while so loud as to diminish the impact of the orchestra the solos bristle with energy and commitment. (In 2010 Pristine Audio released a remarkable "accidental stereo" version by Andrew Ross, derived from meticulous matching of the original mono NBC tape with another recently discovered recording made from a different microphone position.) The earlier London and New York concerts are notably broader, but, while hardly spontaneous, add a sense of humanized repose to the basic straightforward, sharply-focused approach and overriding sense of inexorability. The 1940 is better recorded and arresting in its ardent assertiveness, but the 1938, despite higher constant background hiss and blasty climaxes, has a richer acoustical blend and fuller dynamic range. Each has glorious solo singing and concludes with a chilling statement of the soprano's final lines, all the more effective emerging from a context of casual subtlety. stemming from his personal association with the composer which began when he played cello under Verdi's baton at the premiere of Aida – and to the Requiem itself, which he led in 1902 to mark the first anniversary of Verdi's death, and for a final time in 1951 to commemorate the 50th. All of his three recordings are magnificent and presumably reflect Verdi's own approach of constant pacing, minimal inflection and telling detail. Yet, at least with respect to their vastly different pacing, they defy any attempt at a monolithic guide for idiomatic interpretation. The 1951 recording of a Carnegie Hall concert is the most widely-circulated, yet Toscanini reportedly was ashamed and refused to release it until rehearsal segments were spliced in. Abetted by the tight pace, there's a palpable tension, with nearly every phrase tightly-wound, and while so loud as to diminish the impact of the orchestra the solos bristle with energy and commitment. (In 2010 Pristine Audio released a remarkable "accidental stereo" version by Andrew Ross, derived from meticulous matching of the original mono NBC tape with another recently discovered recording made from a different microphone position.) The earlier London and New York concerts are notably broader, but, while hardly spontaneous, add a sense of humanized repose to the basic straightforward, sharply-focused approach and overriding sense of inexorability. The 1940 is better recorded and arresting in its ardent assertiveness, but the 1938, despite higher constant background hiss and blasty climaxes, has a richer acoustical blend and fuller dynamic range. Each has glorious solo singing and concludes with a chilling statement of the soprano's final lines, all the more effective emerging from a context of casual subtlety.

- Guido Cantelli – New York Philharmonic, 1955

(77 minutes, Archipel CD) — In a sense, this is a fourth Toscanini reading – a concert led by his protégé, who generally applies the same unadorned, impersonal outlook as the Maestro himself. Yet, while tempos are fleet, the overall feeling is more relaxed, trading Toscanini's coiled tension for a more empathetic and natural sensitivity, and the recording quality far outstrips any of the Maestro's. (77 minutes, Archipel CD) — In a sense, this is a fourth Toscanini reading – a concert led by his protégé, who generally applies the same unadorned, impersonal outlook as the Maestro himself. Yet, while tempos are fleet, the overall feeling is more relaxed, trading Toscanini's coiled tension for a more empathetic and natural sensitivity, and the recording quality far outstrips any of the Maestro's.

- Carlo Sabajno – La Scala, 1927 (76 minutes, Pearl CD) — While no known recording matches Verdi's own breathless tempos, several older ones tend to come far closer than any modern one. This, the very first recorded performance of the Verdi Requiem, is bracing and keen, excitingly conducted with fine pacing and a natural flow. Yet, despite a wide dynamic range for its time, deficiencies in the recording apparatus conspire to undermine the modern listening experience, from a barely audible bass drum to an ear-splittingly shrill soprano whose tremulous nervous vibrato deflects any sense of unified purpose, and solo voices that far too often overwhelm the full chorus and orchestra (although the bass of Ezio Pinza is captured with commanding presence).

- Tullio Serafin – Rome Opera, 1939 (73 minutes, Naxos CD) — With the next studio recording, again from a famous Italian opera conductor, emerged the lure of featuring superstar soloists –

here, Maria Caniglia, Ebe Stignani, Beniamino Gigli and Ezio Pinza, all luminaries of their era. The recording is excellent and the performance sharp and vibrant, bristling with loads of heartfelt personal energy, and quivering with ardent conviction. Although the fastest on record, it still falls several minutes short of Verdi's own score timings. The sheer speed generates visceral excitement unmatched by any other – the Dies irae outbursts are truly frightening – and even the most somber sections gain a lyrical bounciness and classical grace that links the work to its Cherubini predecessor. Yet, the slightly rushed aura tends to diminish the underlying gravity of the work. here, Maria Caniglia, Ebe Stignani, Beniamino Gigli and Ezio Pinza, all luminaries of their era. The recording is excellent and the performance sharp and vibrant, bristling with loads of heartfelt personal energy, and quivering with ardent conviction. Although the fastest on record, it still falls several minutes short of Verdi's own score timings. The sheer speed generates visceral excitement unmatched by any other – the Dies irae outbursts are truly frightening – and even the most somber sections gain a lyrical bounciness and classical grace that links the work to its Cherubini predecessor. Yet, the slightly rushed aura tends to diminish the underlying gravity of the work.

- Ferenc Fricsay – RIAS, 1953 (75 minutes, DG CD) — Nearly as fleet is this beautifully integrated reading, in which the soloists tend to make more modest contributions and thus seem a more unified and blended component of the overall conception. Despite an attenuated bass drum, the recording is fully detailed, from which some thrilling moments emerge, including the relentless swelling brass that launch the Tuba mirum. The liner notes observe that this recording was made in turbulent times, shortly after Soviet suppression of the Berlin uprising, which perhaps accounts for its gripping alliance of impassioned outlook, dark tone and hair-raising climaxes.

- Victor de Sabata – La Scala, 1954 (95 minutes, Angel/EMI LP) — The overall conception recalls Toscanini's internalization of the drama, but with less intensity and greater warmth.

Notably, this is the first recording that would announce a new trend of far more leisurely pacing that's undeniably effective. Seemingly at odds with the accelerating pace of modern life, the result lends a wonderfully smooth flow that places primary emphasis on the chorus and creates an aura of serene spirituality that necessarily eludes faster readings. The famed soloists all remain ensconced within the overall texture (although Elizabeth Schwartzkopf invests her soprano role with character from her vast experience as a lieder recitalist), yet de Sabata constantly fascinates with distinctive choral swells, slight pauses and other personal touches that enliven the overall reverential ambiance. Notably, this is the first recording that would announce a new trend of far more leisurely pacing that's undeniably effective. Seemingly at odds with the accelerating pace of modern life, the result lends a wonderfully smooth flow that places primary emphasis on the chorus and creates an aura of serene spirituality that necessarily eludes faster readings. The famed soloists all remain ensconced within the overall texture (although Elizabeth Schwartzkopf invests her soprano role with character from her vast experience as a lieder recitalist), yet de Sabata constantly fascinates with distinctive choral swells, slight pauses and other personal touches that enliven the overall reverential ambiance.

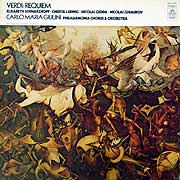

- Carlo Giulini – Philharmonia, 1964 (87 minutes, EMI CD) — This is perhaps the most universally acclaimed of all readings of the Verdi Requiem. Perhaps the highest compliment that can be paid is that it's hard to characterize and neutral in a positive sense of just presenting the music with moderation in a gorgeous, heartfelt reading in which all the forces are smoothly and fully integrated. Yet, this is not just pretty music, but powerful art infused with emotion and a forceful attitude. Like all masterworks, it admits multiple valid interpretations, no single one of which can completely convey its essence, but none is explored here. So with all due respect to those who revere it, I find this performance somewhat lacking and fundamentally unsatisfying. While most of the moderate or slower recordings merely sprawl the work onto a second CD, this one adds fine readings of the Quatro Pezzi Sacri ("Four Sacred Pieces"), Verdi's four final works.

- Robert Shaw – Atlanta, 1987 (84 minutes, Telarc) — Same here. Perhaps the most acclaimed Requiem recording of the digital era,

it boasts undeniably beautiful playing and singing, impressive massive sonorities (bolstered by lots of atmospheric echo), superb choral work (as is expected from Toscanini's choral director) and a fine recording from which subtle textures constantly emerge. Yet, this reading ultimately seems too polite and finely manicured and leaves me rather cold, something a work so full of passion and philosophical probing shouldn't do. Shaw, too, adds a nice bonus, though – a half-hour of Verdi opera choruses that seem more spirited than the Requiem and suggest a mightier performance that might have been. it boasts undeniably beautiful playing and singing, impressive massive sonorities (bolstered by lots of atmospheric echo), superb choral work (as is expected from Toscanini's choral director) and a fine recording from which subtle textures constantly emerge. Yet, this reading ultimately seems too polite and finely manicured and leaves me rather cold, something a work so full of passion and philosophical probing shouldn't do. Shaw, too, adds a nice bonus, though – a half-hour of Verdi opera choruses that seem more spirited than the Requiem and suggest a mightier performance that might have been.

- Eugene Ormandy – Philadelphia Orchestra, Westminster Chorus, 1964 (83 minutes, Sony) — And again. I'm including this as a pioneer of sorts, as it was among the first analog recordings to be reissued on SACD in early 2000 (although I haven't heard it in that format). At the time, comments tended to dub it a "classic," but despite the seeming compliment focused on sonic quality (not always flatteringly), with little mention of the performance itself, and with good reason – while technically adept with all constituent elements securely in place, it's generally bereft of feeling or compulsion. Although the Rex tremendae and Quam olim Abrahae segments give frustratingly brief glimpses of passion (why there, though?), the rest contains barely a hint of the far-reaching exploration and psychological struggle that were so crucial to Verdi's outlook. On the LPs, at least, the solo balance heavily favored the men, a curious gender twist that seemed to suppress the female voices upon which Verdi seized as the vehicle to express his innermost thoughts; while otherwise bizarre and pointless, ironically, this produced a magnificent closing in which soprano Lucina Amara effortlessly faded with the subtlest wisp into the anonymity of the chorus, but the gesture, standing alone and following an hour of largely vapid music-making, lacks whatever impact it might otherwise have had.

- Valery Gergiev – Kirov Orchestra and Chorus, 2001

(84 minutes, Philips) — One more curiousity of sorts ... While superlatives in classical music are always risky, it’s safe to say that of all the recordings of the Verdi Requiem this one has generated the most controversy (and that, in itself, is a rare achievement in the genteel world of serious music criticism). The outpouring of contention has nothing to do with Gergiev’s dramatic leadership, the exciting, rough-hewn playing of his orchestra, the fine singing of the chorus or the distinguished soprano (Renee Fleming) , mezzo (Olga Borodina) or bass (Ildebrando D'Archangelo). Rather, nearly the entire focus is upon casting as the tenor crossover megastar Andrea Bocelli, whose non-classical achievements include duets with Celine Dion and Mary J. Blige, a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, multi-platinum albums, designation as one of People magazine’s “50 Most Beautiful People,” and acclaim ranging from Pavarotti to Oprah and even the Pope. Yet, while adored by legions of fans, he’s routinely savaged by serious critics and other singers (the latter just perhaps out of envy of his astounding fame). In a scathing New York Times review of a 2006 concert, Bernard Holland cited Bocelli’s thin, rasping, poorly supported tone, awkward phrasing and jumbled rhythm, likening his high notes to “the onset of strangulation.” Here, Bocelli sounds fine in quiet sections and blends well into soft ensembles, but otherwise is nasal, brash, strained and awkward compared to the others’ rich confidence and effortless power in more energetic or exposed sections. But he’s a cultural phenomenon, and if he can lead just a few of his worshipful admirers to explore some great music, I guess that’s OK. (84 minutes, Philips) — One more curiousity of sorts ... While superlatives in classical music are always risky, it’s safe to say that of all the recordings of the Verdi Requiem this one has generated the most controversy (and that, in itself, is a rare achievement in the genteel world of serious music criticism). The outpouring of contention has nothing to do with Gergiev’s dramatic leadership, the exciting, rough-hewn playing of his orchestra, the fine singing of the chorus or the distinguished soprano (Renee Fleming) , mezzo (Olga Borodina) or bass (Ildebrando D'Archangelo). Rather, nearly the entire focus is upon casting as the tenor crossover megastar Andrea Bocelli, whose non-classical achievements include duets with Celine Dion and Mary J. Blige, a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, multi-platinum albums, designation as one of People magazine’s “50 Most Beautiful People,” and acclaim ranging from Pavarotti to Oprah and even the Pope. Yet, while adored by legions of fans, he’s routinely savaged by serious critics and other singers (the latter just perhaps out of envy of his astounding fame). In a scathing New York Times review of a 2006 concert, Bernard Holland cited Bocelli’s thin, rasping, poorly supported tone, awkward phrasing and jumbled rhythm, likening his high notes to “the onset of strangulation.” Here, Bocelli sounds fine in quiet sections and blends well into soft ensembles, but otherwise is nasal, brash, strained and awkward compared to the others’ rich confidence and effortless power in more energetic or exposed sections. But he’s a cultural phenomenon, and if he can lead just a few of his worshipful admirers to explore some great music, I guess that’s OK.

-

Leonard Bernstein – London Symphony, 1970

(91 minutes, Sony) – Many other recordings, and most of the early ones, are led by esteemed Italian opera specialists, who necessarily form their readings into that mold and exemplify one prong of the constant debate over the essential nature of the work. Bernstein unabashedly represents Verdi's theatrical side, and provides a superbly crisp and dramatic account that bristles with bold energy and owes far more to the stage than the pulpit (and American brashness than European tradition), with vivid characterization brought home through an admirably detailed recording (originally issued in quadraphonic formats). (91 minutes, Sony) – Many other recordings, and most of the early ones, are led by esteemed Italian opera specialists, who necessarily form their readings into that mold and exemplify one prong of the constant debate over the essential nature of the work. Bernstein unabashedly represents Verdi's theatrical side, and provides a superbly crisp and dramatic account that bristles with bold energy and owes far more to the stage than the pulpit (and American brashness than European tradition), with vivid characterization brought home through an admirably detailed recording (originally issued in quadraphonic formats).

- Riccardo Muti – Philharmonia, 1979

(86 minutes, EMI) – Although he would re-record the Verdi Requiem at La Scala with Pavarotti and Company barely a decade later, Muti’s Philharmonia venture reflects the bold animation of youth, with its emphatic phrasing, impulsive tempos, colossal dynamics, minimal pauses between sections and ardent singing that verges on verismo. Indeed, as would be expected from a conductor steeped in Italian opera, the vocalists dominate the texture. As Geoffrey Crankshaw observed in his LP notes, Muti treats the soloists as fully-realized operatic characters and thus creates a sense of the individual within the context of humanity that immeasurably enhances the feeling of catharsis. Among many uncommon highlights, the close blend of soprano (Renata Scotto) and mezzo (Agnes Baltsa) vibrato in the Recordare is utterly ravishing and brims with inner feeling. The sheer drama of this reading may not appeal to all – the initial appearance of Muti’s rushed pacing of the Dies Irae may magnify the terror of the text, while its two reiterations sacrifice musical continuity in the process – yet the overall impact remains compelling. The LP was graced with additional fascinating notes in which Father David Evans traced the source and significance of each line of text of the ancient prayer. (86 minutes, EMI) – Although he would re-record the Verdi Requiem at La Scala with Pavarotti and Company barely a decade later, Muti’s Philharmonia venture reflects the bold animation of youth, with its emphatic phrasing, impulsive tempos, colossal dynamics, minimal pauses between sections and ardent singing that verges on verismo. Indeed, as would be expected from a conductor steeped in Italian opera, the vocalists dominate the texture. As Geoffrey Crankshaw observed in his LP notes, Muti treats the soloists as fully-realized operatic characters and thus creates a sense of the individual within the context of humanity that immeasurably enhances the feeling of catharsis. Among many uncommon highlights, the close blend of soprano (Renata Scotto) and mezzo (Agnes Baltsa) vibrato in the Recordare is utterly ravishing and brims with inner feeling. The sheer drama of this reading may not appeal to all – the initial appearance of Muti’s rushed pacing of the Dies Irae may magnify the terror of the text, while its two reiterations sacrifice musical continuity in the process – yet the overall impact remains compelling. The LP was graced with additional fascinating notes in which Father David Evans traced the source and significance of each line of text of the ancient prayer.

- Igor Markevitch – Moscow Philharmonic, State Academic Chorus, 1961 (83 minutes, Parliament LP) — This performance, too, stands apart from European tradition.

As an experiment in cultural exchange, Markevitch returned to his homeland, which he had left before the Russian Revolution. (A review in Musical America provides a quaint reminder of those Cold War times – it begins: "The Russians do not intend to devote their efforts only to the manufacture of rockets," and paints the project as a Soviet effort to compete with presumably superior Western cultural achievements.) In any event, the total timing is deceptive, as Markevitch's fresh, volatile approach features extreme tempos both fast and slow, romanticized phrasing, blaring brass and emphatic pauses. A young Galina Vishnevskaya's forceful soprano paces an assertive, rugged and occasionally rough-hewn presentation, abetted by a somewhat crude recording, that suggests the sincerity of the composer and the essential struggle of his concept. As an experiment in cultural exchange, Markevitch returned to his homeland, which he had left before the Russian Revolution. (A review in Musical America provides a quaint reminder of those Cold War times – it begins: "The Russians do not intend to devote their efforts only to the manufacture of rockets," and paints the project as a Soviet effort to compete with presumably superior Western cultural achievements.) In any event, the total timing is deceptive, as Markevitch's fresh, volatile approach features extreme tempos both fast and slow, romanticized phrasing, blaring brass and emphatic pauses. A young Galina Vishnevskaya's forceful soprano paces an assertive, rugged and occasionally rough-hewn presentation, abetted by a somewhat crude recording, that suggests the sincerity of the composer and the essential struggle of his concept.

- Fritz Reiner – Vienna Philharmonic, 1960 (96 minutes, Decca) — Like Toscanini, Reiner developed a reputation as a strict disciplinarian. Predictably, he keeps the limpid beauty of his soloists under control and leads his forces with calm precision to avoid either tedium or overt affection and manages to cast a stronger eye on eternity than on stagecraft. While the Dies irae eruptions adhere to normal tempos, nearly all the other sections are considerably more deliberate than usual, giving rise to a sustained mood of respectful awe, but more intellectualized than tender. The LP set originally was issued in a deluxe RCA Soria box with a lavishly illustrated and annotated 12x12 booklet. (Remember when you actually could read liner notes without a microscope?)

- Sergiu Celibidache – Munich Philharmonic, 1993 (102 minutes, EMI) — While the other readings all are distinctive in various ways, Celibidache's is genuinely unique.

Neither operatic nor pious, the pace is slowed to such an extreme that all hint of drama or impulse is banished into an abstract state of bliss, a realm beyond fear or emotion where only pure music is left. Typical of his approach, Celibidache lavishes exquisite attention on detail, textures, balance and the layering of sound, with a precision derived from fanatic concentration and scrupulous rehearsal, in which each note and phrase is unerringly shaped. The result is a thoroughly elegant, rarified, sublime experience that takes the work into a new spiritual dimension. The audience can hardly be blamed for keeping silent for a quarter-minute after the final note fades. Neither operatic nor pious, the pace is slowed to such an extreme that all hint of drama or impulse is banished into an abstract state of bliss, a realm beyond fear or emotion where only pure music is left. Typical of his approach, Celibidache lavishes exquisite attention on detail, textures, balance and the layering of sound, with a precision derived from fanatic concentration and scrupulous rehearsal, in which each note and phrase is unerringly shaped. The result is a thoroughly elegant, rarified, sublime experience that takes the work into a new spiritual dimension. The audience can hardly be blamed for keeping silent for a quarter-minute after the final note fades.

- Nicholas Harnoncourt – Vienna Philharmonic, Arnold Schoenberg Choir, 2004 (88 minutes, RCA) — Although the first recording to be based on a new critical edition of the score, the differences are subtle (which is to say that even with score in hand I couldn't hear them). More significant is Harnoncourt's background in historically-informed performance practices that guides his work. Here, balances emphasize the middle parts of the chorus to offset the sopranos' usual dominance, the choral forces are adjusted down to as few as four singers to a part, portamento (sliding between notes for emphasis) is limited to a few instances specified by Verdi, and the chorus is split into two halves arrayed stage right and left to emphasize their interplay in the Sanctus. Yet, the performance overall is rather dry and intellectualized, the Dies irae more a polite knocking on the doors of heaven than storming the gates. Even without playback of the SACD layer, the regular stereo soundstage is clear and convincing. While live, the audience is so quiet as to have been either bound and gagged or, more likely, utterly rapt.

- Ricardo Chailly – Orchestra Sinfonico e Coro di Milano Guiseppe Verdi, 2001

(Decca) — For a fascinating comparison, Chailly presents a number of miscellaneous Verdi choral works, including the original version of the Libera me written for the Rossini mass. The crisp and taut performance is a revelation, as it clearly rebuts the implication in so much commentary to the effect that that Verdi's contribution to his Rossini project was merely a primitive forebear of the wondrous movement that ultimately concluded the Requiem. Not so – except for a more fully-developed and unsettling Dies irae section (which gains considerable weight through repetition from the earlier movement), the ultimate concept and impact are nearly intact. And Rosen notes that Verdi wrote it in a mere four days! In essence, then, the entire Requiem, which grew from this initial seed, was a single spontaneous flash of inspiration, born of Verdi's irrepressible passion to present to the world a sonic vision of the essence of his beloved country and its foremost cultural hero. (Decca) — For a fascinating comparison, Chailly presents a number of miscellaneous Verdi choral works, including the original version of the Libera me written for the Rossini mass. The crisp and taut performance is a revelation, as it clearly rebuts the implication in so much commentary to the effect that that Verdi's contribution to his Rossini project was merely a primitive forebear of the wondrous movement that ultimately concluded the Requiem. Not so – except for a more fully-developed and unsettling Dies irae section (which gains considerable weight through repetition from the earlier movement), the ultimate concept and impact are nearly intact. And Rosen notes that Verdi wrote it in a mere four days! In essence, then, the entire Requiem, which grew from this initial seed, was a single spontaneous flash of inspiration, born of Verdi's irrepressible passion to present to the world a sonic vision of the essence of his beloved country and its foremost cultural hero.

For further reading, I found two books especially helpful. David Rosen's monograph, Verdi's Requiem (Cambridge University, 1995), covers the subject with lots of background information and an analysis of each section that, while detailed, avoids becoming mired in hyper-technical jargon or musicological detail that would elude all but the most thoroughly trained professionals. George Martin's Aspects of Verdi (Dodd, Mead & Company, Inc., 1988) devotes a full chapter to Manzoni as Verdi's inspiration for his work. Of the liner notes to the many LPs and CDs cited above, a standout is the insightful comments and compilation of Verdi correspondence provided by William Weaver for the RCA Soria booklet in the deluxe original edition of the Reiner LP set.

Copyright 2009 by Peter Gutmann

|