|

In our time of sterile mobile and home listening environments we tend to overlook the sense of space that has always been an essential part of the music experience. Indeed, it seems ironic that our most sophisticated multi-channel playback systems merely try to replicate the acoustic atmosphere that our forebears took for granted as a basic element of their encounters with music. Perhaps more than any other work, Hector Berlioz's 1837 Grande Messe des Morts ("Great Mass for the Dead," which we'll refer to as his Requiem) serves as a reminder of the sheer sonic breadth that so often is missing nowadays.

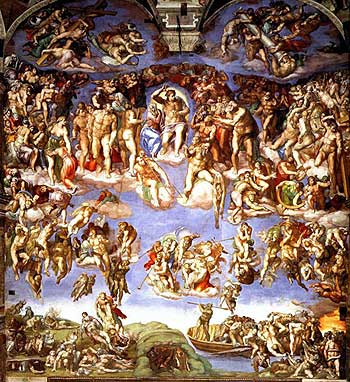

![]() A requiem seems an improbable attraction for a composer who considered himself an agnostic. Although Berlioz retained warm memories of his religious upbringing, he referred to God as "standing aloof in his infinite unconcern," dismissed worship as "revolting and absurd," called Catholicism "charming now that it no longer burns people," and belittled Michelangelo's colossal Last Judgment as a total disappointment: "All I can see in it is a scene of torture in hell but nothing resembling the final gathering of humanity."

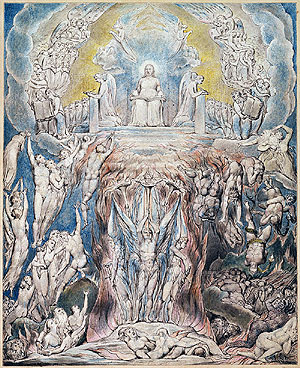

A requiem seems an improbable attraction for a composer who considered himself an agnostic. Although Berlioz retained warm memories of his religious upbringing, he referred to God as "standing aloof in his infinite unconcern," dismissed worship as "revolting and absurd," called Catholicism "charming now that it no longer burns people," and belittled Michelangelo's colossal Last Judgment as a total disappointment: "All I can see in it is a scene of torture in hell but nothing resembling the final gathering of humanity."

Berlioz's cynical attitude colors perceptions that his Requiem is predominantly secular.

Berlioz as a young man |

Michelangelo's Last Judgment |

In that light, religion can be seen as a personal quest for meaning in life, a quest that becomes ever more complex and challenging as society and its values evolve, and for which the pat answers of the past no longer can fully satisfy. Nowhere is this more challenging than in our need to face death. Thus, the Berlioz Requiem can be seen as representing a rejection of the constrictions of established ritual and a leap into a modern approach that was (and perhaps still is) bound to offend religious purists. In that light, Colin Davis wrote that Berlioz is not for those who avoid disturbance, seek logical patterns or indulge favorite emotions, but rather "for those who admit to themselves the inherent discrepancies of this fallen universe, who are no longer surprised that love and hate, violence and tenderness, Christ and the Devil, each call the other into being" and thus will find a reflection of their own psyche and knowledge (and, we might add: mortal fear). Consistent with his approach, Berlioz took a rather free hand with the text. The prescribed liturgy of a requiem consists of the normal mass without the celebratory Gloria and the doctrinaire Credo sections, but adding the Dies Irae (Day of Wrath), a medieval Latin hymn comprising 18 tightly-rhymed three-line stanzas that mix a description of the day of judgment with prayers for penitence. Cairns contends that despite its relentless structure and the "transcendent doggerel of its brief, harsh lines" the Dies Irae irresistibly appealed to the dramatist in Berlioz, who spread it out over five of the work's ten movements, and thus it became "the heart and over half the substance" of his Requiem. Amber Broderick notes that Berlioz variously omits, repeats and scrambles the original verses so as to shift focus to the individual, with expressive overlaps and broken phrases that suggest the stammering of a nervous sinner. To D. Kern Holoman, the result of Berlioz's editing of the prescribed order is a carefully-ordered progression, a dialog between the hellish and the celestial, the personal and the universal.

![]() Although the dramatic style of his Requiem represents a clear break from its predecessors, Berlioz did draw upon models and influences. As general inspiration for its mammoth scale, pride in Napoleon's exploits fostered vast public celebrations (and numerous musical compositions and performances on a heroic scale to match), which Nick Jones relates to the collective consciousness of "a symbolic representation of the whole nation united in religious and patriotic expression."

Although the dramatic style of his Requiem represents a clear break from its predecessors, Berlioz did draw upon models and influences. As general inspiration for its mammoth scale, pride in Napoleon's exploits fostered vast public celebrations (and numerous musical compositions and performances on a heroic scale to match), which Nick Jones relates to the collective consciousness of "a symbolic representation of the whole nation united in religious and patriotic expression."

Luigi Cherubini |

Jean-François Leseur |

An especially intriguing precedent is Berlioz's own Missa Solonnelle, written in 1824 when he was just 21. Although in his Memoires he claimed to have burned it, presumably as a juvenile embarrassment, the manuscript was found in an Antwerp organ loft in 1991, where it had been stashed for a century by the brother of a violinist to whom Berlioz may have given it in lieu of a fee. Its reappearance was hailed by Gramophone as "the most exciting musical discovery of modern times" and by Classics Today as "the musicological highpoint of the second half of the 20th century." Heard today, it sounds remarkably accomplished and often quite inventive, with some especially effective touches – a potent accretion to the Kyrie climax, a bouncy Gloria, and a concluding Domine salvum bristling with feral energy. While he repurposed elements of the Missa Solonnelle for later works (most notably the languid theme of the Scène aux champs in the Symphonie Fantastique), the most telling section is the vivid Resurrexit, whose introductory fanfares, massed tympani and declamation form an embryonic version of the apocalyptic Tuba mirum of the Requiem. Joseph Braunstein notes two other earlier Berlioz works that paved the way toward the novelty and grand scale of the Requiem: an 1829 recitative accompanied by eight sets of harmonically-tuned kettledrums and an 1831 oratorio depicting the last day on earth with an extra massive orchestra behind the scene and four wind and brass groups arrayed at the compass points; Berlioz relished that: "The combination would be entirely new, and a thousand possibilities, which could not be realized with usual means, could be drawn out of these sounding masses." Although the oratorio was never performed, its striking inspirations continued to simmer, awaiting a suitable opportunity to emerge.

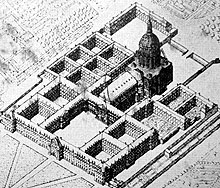

![]() The Requiem was commissioned in April 1837 for a July 28 service to be held in the vast Parisian Church of the Invalides to commemorate the seventh anniversary of heroes fallen in the July 1830 revolution. Under intense pressure to meet the deadline (and out of fear that the retiring Interior Minister's successor might rescind the commission), Berlioz claimed that he felt as if his brain would explode from the press of ideas and devised a shorthand to sketch out the entire work, which he then orchestrated in June. But even as rehearsals proceeded the event was trimmed and the musical portion cancelled due both to the depletion of available funds by a lavish royal wedding and the resistance of foreign governments to glorifying the heroes of insurgency.

The Requiem was commissioned in April 1837 for a July 28 service to be held in the vast Parisian Church of the Invalides to commemorate the seventh anniversary of heroes fallen in the July 1830 revolution. Under intense pressure to meet the deadline (and out of fear that the retiring Interior Minister's successor might rescind the commission), Berlioz claimed that he felt as if his brain would explode from the press of ideas and devised a shorthand to sketch out the entire work, which he then orchestrated in June. But even as rehearsals proceeded the event was trimmed and the musical portion cancelled due both to the depletion of available funds by a lavish royal wedding and the resistance of foreign governments to glorifying the heroes of insurgency.

Les Invalides in 1734 |

The premiere was a huge triumph, widely reported and acclaimed. Yet, as Barzun notes, its success was not immediately apparent, as the solemnity of the occasion precluded applause and so "whether the audience was moved or bored or bewildered ... it [was] impossible to say." Indeed, there were severe challenges that compromised the reception. Although Berlioz hired the best musicians in Paris, he could afford only about half of the 800 he had wanted. The work was not performed as a continuous whole but rather its movements were interspersed while priests chanted a Gregorian funeral service throughout. Not only did this drown out the many softer passages that the listeners were seated too far away to hear but, as Barzun notes, it diverted attention from music to ritual and disrupted the flow, including the striking contrasts between movements. Even so, the satiric weekly newspaper Le Figaro related that even though the performers did not know the work thoroughly they made a deep impression.

1846 caricature of Berlioz conducting |

Subsequent commentators tend to share the composer's sense of awe but with due regard for his perceived limitations. Holoman suggests that Berlioz intrigues us while frustrating scholars since his orientation was so consistently out of step with 19th century formal and harmonic practice as to purposefully defy placement in the continuity of orderly esthetic development. This was due in large part to his spontaneity. Thus Percy Scholes credits Berlioz with direct expression of sincere emotion and Charles Munch contends that his genius lay in building tempestuously rather than according to rigid expectations and analogizes his work to a vast fresco spattered with broad splotches of color. Berlioz himself wrote: "The prevailing characteristics of my music are passionate expression, intense ardor, rhythmical animation and unexpected turns." Others cite the lengthy unfolding of unconventional, large-scale melodies, which Berlioz proudly defended as: "so unlike the little absurdities to which the term is applied by the lower stratum of the musical world." Yet some critics regarded these same hallmarks as blemishes. Writing in 1904, Hadow summed it up well: "No composer has ever written with more spontaneous force or with more vehement or volcanic energy. His imagination always seems at white heat … in an impetuous torrent which levels all obstacles and overpowers all restraint. There is, indeed, a singular perversity in Berlioz's music. … Time and again he ruins his cause by subordinating beauty to emphasis and is so anxious to impress that he forgets how to charm." Sigmund Spaeth contended that Berlioz attempted more than he could accomplish. Reconciling these views, Hugh Macdonald insists that Berlioz's idiosyncratic style simply requires familiarity as a gate to understanding. Recordings now afford that opportunity.

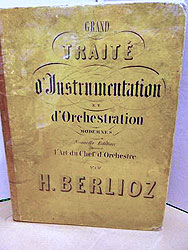

![]() While other aspects of Berlioz's art may be disputed, one area of universal praise is his mastery of orchestration. Alone among the great composers, Berlioz never studied the piano, but only dabbled in flute and guitar. He was far from ashamed of this "gap" in his musical arsenal which he found liberating: "I feel grateful for the happy chance that forced me to compose freely and in silence, and thus delivered me from the tyranny of the fingers, so dangerous to thought."

While other aspects of Berlioz's art may be disputed, one area of universal praise is his mastery of orchestration. Alone among the great composers, Berlioz never studied the piano, but only dabbled in flute and guitar. He was far from ashamed of this "gap" in his musical arsenal which he found liberating: "I feel grateful for the happy chance that forced me to compose freely and in silence, and thus delivered me from the tyranny of the fingers, so dangerous to thought."

Berlioz's treatise on orchestration |

The Requiem is full of brilliant orchestration, combining Berlioz's deep knowledge with his impulse and daring. Perhaps most palpable are its overtly spectacular passages, and nowhere so striking as in the Tuba mirum. The two grand climaxes are overwhelming, with hundreds of fortissimo voices drowned out by deafening, frantic tremolo drumming – Norman del Mar notes that the whole building will be a mass of reverberation. Yet even there the score reveals an astounding array of subtle arrangement, albeit largely obscured by the sheer volume of the massed forces. While Berlioz specifies 16 tympani, they are tuned to all 12 notes of the chromatic scale and are carefully deployed and layered into numerous chords (and not all harmonious ones at that). Camille Saint-Saëns felt "as if each separate column of each pillar in the church became an organ pipe and the whole edifice a vast organ." Berlioz further separates the tympani into pairs and specifies which are to be played by a single drummer or two, the types of drumsticks and even the manner in which an enormous bass-drum is to be struck (alternating patterns on each side). Perhaps most remarkably, he requires four gongs and ten cymbals that are heard but twice, and then for a grand total of only a few seconds. Admittedly, those climaxes are thrilling, yet the inefficient use of such extravagant resources sorely tempts producers to cut corners (or program works with less lavish demands). Yet, perhaps more than any other aspect, this testifies to the composer's insistence upon uncompromised realization of his vision, practicality be damned.

Equally wondrous are subtle instrumental effects at the opposite end of the emotional spectrum. Del Mar calls the Hostias "perhaps the most unusual movement ever written in terms of instrumental color."

Flutes, trombones and monotone voices in the Hostias |

At the extreme opposite end of the sonic scale from the Tuba mirum is the four-minute Quaerens me, written for a capella six-part chorus (SATTBB) with which, as Robert Lawrence notes, "Berlioz demonstrates that instrumental color was not an indispensable part of his genius." Indeed, many commentators marvel that, despite the huge forces mustered for his Requiem, Berlioz used them so sparingly throughout the course of the entire work. Thus, while del Mar cites it as the largest and most ambitious work in the entire concert repertoire, Holoman admires its introspection and exquisite sparseness. Like all great artists, Berlioz relished the need for contrast and realized that startling drama is far more effective when it emerges occasionally from within a serene setting so as to avoid the fatigue that invariably blunts the impact of a sustained onslaught.

![]() The Requiem nowadays often is vaunted for its extraordinary and spectacular use of space. Yet this facet was hardly novel. Even before Lesueur's 1801 Symphonic Ode, Mozart had written a 1777 Notturno for Four Orchestras, K. 286, in which three smaller ensembles in turn echo the principal body.

The Requiem nowadays often is vaunted for its extraordinary and spectacular use of space. Yet this facet was hardly novel. Even before Lesueur's 1801 Symphonic Ode, Mozart had written a 1777 Notturno for Four Orchestras, K. 286, in which three smaller ensembles in turn echo the principal body.

4 brass orchestras and 16 timpani for the Last Judgment |

Beyond the sheer bulk of its climaxes, the Tuba mirum of the Requiem is renowned for its fanfares of four brass orchestras, each with specified complements of eight to twelve cornets, trumpets, trombones and tubas, to depict the sheer terror of the call to judgment. Curiously, most commentators state that the bands were to be deployed to the extreme corners of the Invalides. Barzun, though, considers this a modern myth that would have precluded precise entrances and points to the specification in the published score that they were to be placed only at the four corners of the vocal and instrumental groups. Yet in most recordings their synchronization is so diffuse as to suggest vast distances for their sounds to travel. In any event, even without extreme separation their impact in the Tuba mirum is truly hair-raising. Typically for Berlioz, despite their reputation as the work's most characteristic feature, the four brass bands are heard only twice more – briefly to underscore the climax of the Rex tremendae, and in the Lacrymosa where their syncopated chords punctuate and intensify the conclusion of the Dies irae. (In addition, 16 trombones and four tubas from the separate bands join the orchestra to add depth to the final Agnus dei.)

Berlioz wrote that the building in which music is played is the most important of all the musical instruments (likening it to the body that contains the music's soul). Yet he believed that most music was habitually played in buildings too large for it. Indeed, during his sojourn in Rome he was dismayed at the inadequacy of the puny papal choir and portable organ within the vast Sistine Chapel. Even so, the Requiem all but demands performance in a suitably massive space. Del Mar asserts that few venues are suitable and that the amazing sonorities can only produce their full effect in a large sacred building. The Invalides was immense and to fill it Berlioz wanted a body of sound proportionate to its scale, including a chorus of 800, but wound up settling for about half. He also had to compromise his ideal orchestra, which he envisioned as 465 players comprising 242 strings (including four 13-foot "octabasses" that would play an octave lower than double basses), 30 harps, 16 horns, 15 clarinets, 12 trombones, 10 flutes, etc. The published score specifies 210 choristers [80 sopranos and altos, 60 tenors and 70 basses], 108 strings [50 violins, 20 violas, 20 celli and 18 contrabasses], 20 winds, 12 horns plus the off-stage brass, but states: "The numbers indicated are only relative. If space permits the chorus may be doubled or tripled and the orchestra proportionately increased. But in the event of an exceptionally large chorus, say 700-800 voices, the entire chorus should only be used for the Dies Irae, the Tuba Mirum and the Lacrymosa, the rest of the movements being restricted to 400 voices." Called upon to defend the required resources, Berlioz contended that warmth of vocal feeling resides in a multitude and that while wind and brass multiplied beyond a certain point become coarse and heavy, they seem powerful rather than merely noisy when played with precision and clarity, qualities upon which he insisted as a conductor. (Lawrence,though, chides critics who focus on the extreme demands as caring more for statistics than artistic content.

![]() Berlioz wrote rather facetiously that: "Composers of funeral music can always be sure that occasions will not be lacking when their work can be heard." Yet due to its dimensions and demands performances of the Requiem were (and still are) quite rare. It was given only four more times during the remaining three decades of Berlioz's life, although on concert tours he conducted isolated movements, especially the Offertorium. Even so, the success of the Requiem led to two further works in which he separately pursued its ceremonial and religious components.

Berlioz wrote rather facetiously that: "Composers of funeral music can always be sure that occasions will not be lacking when their work can be heard." Yet due to its dimensions and demands performances of the Requiem were (and still are) quite rare. It was given only four more times during the remaining three decades of Berlioz's life, although on concert tours he conducted isolated movements, especially the Offertorium. Even so, the success of the Requiem led to two further works in which he separately pursued its ceremonial and religious components.

For the ceremony marking the tenth anniversary of the 1830 Revolution Berlioz wrote a Grande Symphonie funèbre et triomphale, comprised of three sections evoking eruptions of battle amidst a mournful cortege, a funeral oration as the victims were reinterred in a new commemorative monument in the Place de la Bastille, and a hymn of glory as the tomb was sealed. Berlioz recalled that, as with the Requiem, much of its initial audition was drowned out, this time not by chanting priests but by a military drum corps. Initially written for a large symphonic band, in 1842 he added string and choral parts "which, although not obligatory, add considerably to the effect." Wagner, for one, was hugely impressed, rating it "great from the first note to the last, without any morbid frenzy, yet possessing a highly patriotic emotion … that will endure and exalt the courageous as long as the nation bearing the name of France endures!"

comprised of three sections evoking eruptions of battle amidst a mournful cortege, a funeral oration as the victims were reinterred in a new commemorative monument in the Place de la Bastille, and a hymn of glory as the tomb was sealed. Berlioz recalled that, as with the Requiem, much of its initial audition was drowned out, this time not by chanting priests but by a military drum corps. Initially written for a large symphonic band, in 1842 he added string and choral parts "which, although not obligatory, add considerably to the effect." Wagner, for one, was hugely impressed, rating it "great from the first note to the last, without any morbid frenzy, yet possessing a highly patriotic emotion … that will endure and exalt the courageous as long as the nation bearing the name of France endures!"  Yet given the specific occasion for which it was fashioned, performances understandably are even scarcer than for the Requiem. Despite its relative brevity (about 35 minutes) and a vibrant apotheosis, it seems overly long, repetitive, nondescript, largely forgettable background music.

Yet given the specific occasion for which it was fashioned, performances understandably are even scarcer than for the Requiem. Despite its relative brevity (about 35 minutes) and a vibrant apotheosis, it seems overly long, repetitive, nondescript, largely forgettable background music.

Berlioz returned to religious grandeur in an 1849 Te Deum, which he described as a brother to the Requiem. This time there was no commission, and his motive is unclear. Cairns, for one, speculates that as the composer aged he felt a need to reassert ancient values in times of unrest, and not only became nostalgic for the influences and first awakenings of his childhood but harked back even further through the traditions of Western musical history. Thus the work begins with antiphonal chords alternating between orchestra and an organ, which he wanted to be placed at opposite ends of the venue so as to both define the performing space and amplify the symbolic spiritual distance between them. Indeed, throughout the work the organ stands apart from the orchestra and thus retains its own sonority and individuality, suggesting a tension between a sacred service and a secular concert piece. In six movements and featuring two adult choruses, a children's chorus and a solo tenor, it evokes ancient chants and cantus firmus and, dare we say, much of it sounds more like Cherubini than Berlioz would ever want to admit. Declining the bold invention, extreme moods, colossal forces and stunning spectacle of the Requiem, the Te Deum is a thoroughly engaging work, both spiritual and invigorating (and, at 50 minutes, relatively succinct), and concludes with a potent Judex that Berlioz called "without doubt my most grandiose creation." In a departure from its largely conservative bearing, it ends with an extraordinary and presumably personal plea – as Cairns aptly describes it, a pounding rhythm grows in power and urgency, as repeated cries of "non confundar in aeternum" ("let me never be confounded") "sway between splendor and terror like the swing of an enormous bell" – more of a frantic quest for meaning than a celebration of faith.

![]() The Requiem is cast in ten movements. The second through sixth movements comprise the Dies irae poem; the rest convey portions of the Mass. A typical performance runs about 85 minutes.

The Requiem is cast in ten movements. The second through sixth movements comprise the Dies irae poem; the rest convey portions of the Mass. A typical performance runs about 85 minutes.

The Last Judgment – Joos van Cleve, c. 1520 |

The first half of the sinuous theme of the Lacrymosa |

Offeratorium (piano reduction) |

The ravishing Sanctus melody and Hosanna fugue subject |

A concluding string arpeggio and cadence |

![]() As with operas shorn of their essential theatrical component, mere recordings of the Berlioz Requiem cannot possibly convey the full depth and splendor of a rendition by gargantuan forces deployed in a vast enclosed space. Yet, in his review of its first recording Robert Lawrence presciently observed a veiled benefit in condensing the work's massive scale to the modest confines of a home playback environment: "Perhaps the invisibility of the forces employed will oblige the listener to concentrate entirely on what so many commentators have ignored in the work until now – not the mechanical means, which are incidental, but the deeply moving artistic end." Indeed, many are apt to find spirituality far more likely to arise in the solitude and privacy of a home setting than amid large crowds. Even so, Berlioz clearly conceived the Requiem to be experienced on a scale and in a setting that comprise an integral and essential part of the work. Recordings that fail to at least suggest that crucial element raise issues of authenticity. Ideally, an effective recording will manage to reconcile the essence of the Requiem's scale with the reality of the only way most of us will be able to experience it nowadays.

As with operas shorn of their essential theatrical component, mere recordings of the Berlioz Requiem cannot possibly convey the full depth and splendor of a rendition by gargantuan forces deployed in a vast enclosed space. Yet, in his review of its first recording Robert Lawrence presciently observed a veiled benefit in condensing the work's massive scale to the modest confines of a home playback environment: "Perhaps the invisibility of the forces employed will oblige the listener to concentrate entirely on what so many commentators have ignored in the work until now – not the mechanical means, which are incidental, but the deeply moving artistic end." Indeed, many are apt to find spirituality far more likely to arise in the solitude and privacy of a home setting than amid large crowds. Even so, Berlioz clearly conceived the Requiem to be experienced on a scale and in a setting that comprise an integral and essential part of the work. Recordings that fail to at least suggest that crucial element raise issues of authenticity. Ideally, an effective recording will manage to reconcile the essence of the Requiem's scale with the reality of the only way most of us will be able to experience it nowadays.

Writing in 1948, Lawrence bemoaned the dearth of performances, which led to the Requiem being "more of a legend than an actuality." Recordings already had begun to remedy that.

- Jean Fournet, Choeurs Emile Passani, Grand Orchestre de Radio-Paris, Georges Jouatte (tenor) (1943, French Columbia 78s, 79')

Matthew Tepper, for one,

suggests that this recording of a quintessentially French powerhouse made at the height of the Vichy regime may have been a gesture of cultural pride, if not political defiance, and indeed the singing resounds with considerable spirit. (Presumably extra-musical considerations led David Hall in his 1948 Record Book to proclaim it the most important recording made anywhere during the War – a mere seven years later, in his updated Disc Book he never even mentioned it!) Perhaps due to wartime shortages, the choral forces seem severely reduced so much that occasionally individual voices emerge, but in part this may stem from close microphone placement. Yet the venue – the enormous Gothic/Renaissance church of St. Eustache in Les Halles (where Berlioz led the premiere of his Te Deum and all three subsequent performances of the Requiem) – contributes reverberant decay. The result is a claustrophobic perspective of being uncomfortably squeezed tight amid a vast hollow chamber. Generally dull sonics, compressed dynamics and skewed balances further tend to erase subtlety, compromise the power of the climaxes and obscure much orchestral detail – the brass entrances in the Tuba mirum are wimpy, drums are barely audible, the Hostias trombones tend to drown out the flutes and the overly-prominent Sanctus tenor sounds more operatic than meditative. In his review, Lawrence asserts that the Requiem is not mechanically difficult to perform and lies well within the grasp of student groups, and so "it is the synchronization of the massed musicians … that places the burden almost entirely upon the conductor." In that respect Fournet, barely 30 but already respected as an exemplar of French tradition, succeeds by merely mustering his forces with moderate pacing (but not as fleet as the overall timing might suggest – the entire first half of the Sanctus is omitted) and few particular interpretive touches, although the Offertorium is nicely atmospheric, the Lacrymosa generates imposing cumulative energy and the overall feeling is winningly sweet and charming. Yet, while we tend to consider the French approach to music to be smooth, reserved and gentle, aside from its considerable historical importance this pioneering set leaves much unsaid and unfelt.

suggests that this recording of a quintessentially French powerhouse made at the height of the Vichy regime may have been a gesture of cultural pride, if not political defiance, and indeed the singing resounds with considerable spirit. (Presumably extra-musical considerations led David Hall in his 1948 Record Book to proclaim it the most important recording made anywhere during the War – a mere seven years later, in his updated Disc Book he never even mentioned it!) Perhaps due to wartime shortages, the choral forces seem severely reduced so much that occasionally individual voices emerge, but in part this may stem from close microphone placement. Yet the venue – the enormous Gothic/Renaissance church of St. Eustache in Les Halles (where Berlioz led the premiere of his Te Deum and all three subsequent performances of the Requiem) – contributes reverberant decay. The result is a claustrophobic perspective of being uncomfortably squeezed tight amid a vast hollow chamber. Generally dull sonics, compressed dynamics and skewed balances further tend to erase subtlety, compromise the power of the climaxes and obscure much orchestral detail – the brass entrances in the Tuba mirum are wimpy, drums are barely audible, the Hostias trombones tend to drown out the flutes and the overly-prominent Sanctus tenor sounds more operatic than meditative. In his review, Lawrence asserts that the Requiem is not mechanically difficult to perform and lies well within the grasp of student groups, and so "it is the synchronization of the massed musicians … that places the burden almost entirely upon the conductor." In that respect Fournet, barely 30 but already respected as an exemplar of French tradition, succeeds by merely mustering his forces with moderate pacing (but not as fleet as the overall timing might suggest – the entire first half of the Sanctus is omitted) and few particular interpretive touches, although the Offertorium is nicely atmospheric, the Lacrymosa generates imposing cumulative energy and the overall feeling is winningly sweet and charming. Yet, while we tend to consider the French approach to music to be smooth, reserved and gentle, aside from its considerable historical importance this pioneering set leaves much unsaid and unfelt.

- Theodore Hollenbach, Chorus and Orchestra of the Rochester Oratorio Society, Ray de Voll (1954, Columbia Entré LPs, 88')

The Fournet set was not released in the US until 1948, perhaps a measure of the indifference with which the work was regarded at the time (or which A&R staff assumed).

A further indication of low expectations came with this second recording by relative unknowns, which Columbia released directly as a gatefold album on its budget ($2.95) Entré label that featured mostly light classical programs and LP editions of older 78 rpm Masterworks sets. (Its 1960s reissue would be on the even cheaper $1.98 Harmony label.) Although never transferred to CD, this set is surprisingly accomplished and well-recorded with a wide dynamic range (even if the climaxes sound a bit undernourished) and well-judged balances that let details emerge naturally, adding considerable interest to even the less overtly dramatic sections. One might expect these comparative neophytes to adhere closely to the score, but they deliver quite a surprise – or, perhaps, shock – with extreme tempos that Cairns dismisses as fluctuating between drastically slow and hysterically fast. In addition, transitions tend to be abrupt rather than the gradual adjustments specified in the score. Yet the departures seem thematically appropriate – a glacial Dies irae (58 quarter notes per minute v. a specified 96) portends the deluge to come with frozen fear and a deliberate Offertorium (11+ minutes vs. a "standard" 6 or so) emphasizes simple rumination, offset by a hurried Lacrymosa that hurls sinners toward judgment with irresistible force and a fleet Hosanna that leaps with joy. Aside from tempos, further liberties are taken in the Lacrymosa by adding a second gong explosion and sustaining the final note. Does such boldness and iconoclasm arise from inexperience or inspiration? Or is it a function of the difference between adhering to Old-World tradition vs. embracing American audacity? Whatever your view on such matters, the Rochester recording provides a fresh and fascinating perspective that deserves far better renown than the neglect to which it is generally relegated in surveys of Requiem recordings.

A further indication of low expectations came with this second recording by relative unknowns, which Columbia released directly as a gatefold album on its budget ($2.95) Entré label that featured mostly light classical programs and LP editions of older 78 rpm Masterworks sets. (Its 1960s reissue would be on the even cheaper $1.98 Harmony label.) Although never transferred to CD, this set is surprisingly accomplished and well-recorded with a wide dynamic range (even if the climaxes sound a bit undernourished) and well-judged balances that let details emerge naturally, adding considerable interest to even the less overtly dramatic sections. One might expect these comparative neophytes to adhere closely to the score, but they deliver quite a surprise – or, perhaps, shock – with extreme tempos that Cairns dismisses as fluctuating between drastically slow and hysterically fast. In addition, transitions tend to be abrupt rather than the gradual adjustments specified in the score. Yet the departures seem thematically appropriate – a glacial Dies irae (58 quarter notes per minute v. a specified 96) portends the deluge to come with frozen fear and a deliberate Offertorium (11+ minutes vs. a "standard" 6 or so) emphasizes simple rumination, offset by a hurried Lacrymosa that hurls sinners toward judgment with irresistible force and a fleet Hosanna that leaps with joy. Aside from tempos, further liberties are taken in the Lacrymosa by adding a second gong explosion and sustaining the final note. Does such boldness and iconoclasm arise from inexperience or inspiration? Or is it a function of the difference between adhering to Old-World tradition vs. embracing American audacity? Whatever your view on such matters, the Rochester recording provides a fresh and fascinating perspective that deserves far better renown than the neglect to which it is generally relegated in surveys of Requiem recordings.

- Dmitri Mitropoulos, Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Vienna State Opera Chorus, Léopold Simoneau (1956, Orfeo CD, 78')

- Dmitri Mitropoulos, Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, North German Radio Chorus, Nicolai Gedda (1956, ICA Classics CD, 82' [on a single CD!])

While both of these concert recordings present the same basic approach

in decent broadcast-quality monaural sound, the Vienna version, dedicated to the memory of Wilhelm Furtwängler, is not only faster but somewhat more forceful and full of effective interpretive touches. Each of the sustained timpani chords in the Dies irae is launched by an emphatic, attention-grabbing downbeat, as if to stress their individuality and musical innovation. In the final iteration of "Rex tremendae" the voices lag the instruments, as if to suggest collective fatigue. The Lacrymosa has a rather rough-hewn feeling suitable to human struggle and slows to add gravity to the approach of the massive climax that arrives after a slight pause to suggest a possible reprieve that soon vanishes to underscore its inescapable finality. Throughout there is a tangible commitment, conveying that this is not just music, nor even the background for a religious rite, but a profound, shared human experience that deeply matters. Little wonder that two decades later Mitropoulos's foremost protégé, Leonard Bernstein, would produce his own stunning recording, infused and resonating with the inspiration of his mentor.

in decent broadcast-quality monaural sound, the Vienna version, dedicated to the memory of Wilhelm Furtwängler, is not only faster but somewhat more forceful and full of effective interpretive touches. Each of the sustained timpani chords in the Dies irae is launched by an emphatic, attention-grabbing downbeat, as if to stress their individuality and musical innovation. In the final iteration of "Rex tremendae" the voices lag the instruments, as if to suggest collective fatigue. The Lacrymosa has a rather rough-hewn feeling suitable to human struggle and slows to add gravity to the approach of the massive climax that arrives after a slight pause to suggest a possible reprieve that soon vanishes to underscore its inescapable finality. Throughout there is a tangible commitment, conveying that this is not just music, nor even the background for a religious rite, but a profound, shared human experience that deeply matters. Little wonder that two decades later Mitropoulos's foremost protégé, Leonard Bernstein, would produce his own stunning recording, infused and resonating with the inspiration of his mentor.

- Hermann Scherchen, Chorus of Radiodiffusion Française, Orchestre du Théâtre National de l'Opera, Jean Giraudeau (1957, Westminster LPs, 98')

At the time of its initial release, this set's claim to fame was having been recorded in the Invalides.

A notice in Billboard proclaimed that this was the first time that the French government had allowed a private firm to use a national monument for profit and boasted that it had cost $25,000 ("one of the largest amounts ever spent on a single album"), required five days, used 41 microphones, and featured a chorus of 130 and an orchestra of 170 comprising "the entire Paris Opera orchestra plus first desk men from every major group in the country." Yet, while the album booklet claimed that the venue was "the scene of its première performance," that's somewhat misleading, as half of the original space had since been partitioned off to create a tomb for Napoleon, and so the remaining chapel was not quite as immense or reverberant. (Even so, in his biography of Leonard Bernstein, who also recorded it there, Humphrey Burton calls the Invalides (or at least what remains of it) "an acoustical death-trap" in which "the musicians had difficulty hearing each other and the concealed pitch-pipes of an electronic organ were of limited success in helping the chorus stay in tune.")

A notice in Billboard proclaimed that this was the first time that the French government had allowed a private firm to use a national monument for profit and boasted that it had cost $25,000 ("one of the largest amounts ever spent on a single album"), required five days, used 41 microphones, and featured a chorus of 130 and an orchestra of 170 comprising "the entire Paris Opera orchestra plus first desk men from every major group in the country." Yet, while the album booklet claimed that the venue was "the scene of its première performance," that's somewhat misleading, as half of the original space had since been partitioned off to create a tomb for Napoleon, and so the remaining chapel was not quite as immense or reverberant. (Even so, in his biography of Leonard Bernstein, who also recorded it there, Humphrey Burton calls the Invalides (or at least what remains of it) "an acoustical death-trap" in which "the musicians had difficulty hearing each other and the concealed pitch-pipes of an electronic organ were of limited success in helping the chorus stay in tune.")

Rather, the Scherchen album is better remembered for two other distinctions. First, it was the first Berlioz Requiem to be issued in stereo (WST 201), although the mono LPs (XWN 2227) boasted greater clarity and appreciably richer sound, a more appropriate acoustic for Berlioz's striking instrumentation and Scherchen's brooding approach. (A few distinctive details suggest that the mono and stereo editions may have been comprised of different takes.) Miking is fairly distant, providing a blended, even blurred, resonant sound that suggests a sense of considerable space and that lends a spiritual dimension to the more delicate parts that seem suspended in the immensity of space, even if depriving the climaxes of the force that greater presence would infer. Compared to prior monaural issues (as well as to Scherchen's own), the four brass bands in his stereo set are distinguished not only by their differing textures but by placement across a wide soundstage, a major step toward replicating at least one dimension of the spatial impression Berlioz intended. As a result, for the first time the dense brass writing becomes rational rather than the incoherent jumble that invariably stems from being compressed into a single channel. A more dubious distinction is the consistently slow pace, as nearly every movement is taken about 25% slower than specified in the score (although the approach to the Tuba mirum climax is curiously rushed). Presumably intended as meditative, the effect seems more funereal and overly respectful, drained of visceral contrast (except in the Rex tremendae, where remarkably vital outbursts consistently challenge the mellow overall setting). Rather than profound and deeply religious, the result struck most commentators as merely monotonous and fatigued. (As Tepper succinctly put it, "Berlioz is not Bruckner!") Indeed, while the softer portions are deeply affecting (the Sanctus boasts a ineffably sweet tenor and an ethereal choir) much of the overall impression is one of resigned acceptance and regret, bypassing the sense of struggle, fear and questioning that seem an essential part of Berlioz's conception. Even so, Scherchen's deliberation serves to exhibit a valid aspect of a rich and multi-faceted work.

- Charles Munch, Boston Symphony Orchestra, New England Conservatory Chorus, Léopold Simoneau (1959, RCA LPs, 84')

Showered with superlatives and constantly reissued, this recording often is cited as the finest of all.

Indeed Munch leads an intensely musical and deeply humane reading with tempos that feel just right (although often slower than the score's specifications), exquisitely smooth dynamics and beautifully-shaped phrases, all nestled in a warm, richly-blended, comforting acoustic. While reviews often cite this recording for its extreme emotion, I simply don't hear it, especially compared to Koussevitzky, Bernstein, et al. Rather, there's just enough color and finely-judged balances to convey the wonders of the score within a context of pensive poetry that provides the departed with respect and a suitably peaceful farewell. Look elsewhere for hair-raising drama – the brass choirs won't startle with melodrama, but rather fit into the realm of idealized human existence. The Sanctus tenor soars with passion yet is unreachably distant, inviting the Hosanna choir to bring us back to our earthly realm. Note that I've stuck with my original RCA Soria vinyl edition (complete with a lavish 12 x 12 book with lots of pictures and legible type – remember those?), so I can't vouch for ensuing tape, LP, CD and SACD incarnations. Munch's 1967 DG remake with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus is conceptually similar but crisper, more forward (including a tenor who sounds like he's in my lap) and falls short of the special mellow atmosphere of the Boston set.

Indeed Munch leads an intensely musical and deeply humane reading with tempos that feel just right (although often slower than the score's specifications), exquisitely smooth dynamics and beautifully-shaped phrases, all nestled in a warm, richly-blended, comforting acoustic. While reviews often cite this recording for its extreme emotion, I simply don't hear it, especially compared to Koussevitzky, Bernstein, et al. Rather, there's just enough color and finely-judged balances to convey the wonders of the score within a context of pensive poetry that provides the departed with respect and a suitably peaceful farewell. Look elsewhere for hair-raising drama – the brass choirs won't startle with melodrama, but rather fit into the realm of idealized human existence. The Sanctus tenor soars with passion yet is unreachably distant, inviting the Hosanna choir to bring us back to our earthly realm. Note that I've stuck with my original RCA Soria vinyl edition (complete with a lavish 12 x 12 book with lots of pictures and legible type – remember those?), so I can't vouch for ensuing tape, LP, CD and SACD incarnations. Munch's 1967 DG remake with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus is conceptually similar but crisper, more forward (including a tenor who sounds like he's in my lap) and falls short of the special mellow atmosphere of the Boston set.

- Sir Thomas Beecham, Royal Philharmonic Chorus and Orchestra, Richard Lewis (1959, BBC CD, 78')

Given his urbane demeanor, one would not expect Beecham to fully realize the Berlioz Requiem,

and to me he really doesn't. This is a Requiem that succeeds on a purely musical level and barely touches its profundity and iconoclasm – an abstract and even classical oratorio à la Handel. And yet although tempos seem too fast and perfunctory, they adhere closely to the score's specifications and do generate a certain momentum and energy of their own, so perhaps that's the pacing and impression Berlioz had in mind. Recorded in concert in London's Royal Albert Hall with 148 voices and 143 players, execution and balances are fine (except for an overly loud and emphatic Sanctus solo) and the fidelity of the 1999 BBC CD edition is a vast improvement over prior "unauthorized" releases. By holding so much in reserve, Beecham affords a few dramatic surprises – the second climax of the Dies irae gains greater force following a rather subdued first one, and the Lacrymosa builds persuasively. Despite the encomia lavished on this recording (and not only from English critics who instintively tend to worship Beecham; "marvelous" – Gramophone; "remarkable" – Classicalcdreview; "a touchstone performance – dramatically perfect" – Tepper), I question whether it serves as a complete realization. But as a purely musical take it works quite well on its own terms– and perhaps is especially suitable for our superficial times and increasingly brief attention spans.

and to me he really doesn't. This is a Requiem that succeeds on a purely musical level and barely touches its profundity and iconoclasm – an abstract and even classical oratorio à la Handel. And yet although tempos seem too fast and perfunctory, they adhere closely to the score's specifications and do generate a certain momentum and energy of their own, so perhaps that's the pacing and impression Berlioz had in mind. Recorded in concert in London's Royal Albert Hall with 148 voices and 143 players, execution and balances are fine (except for an overly loud and emphatic Sanctus solo) and the fidelity of the 1999 BBC CD edition is a vast improvement over prior "unauthorized" releases. By holding so much in reserve, Beecham affords a few dramatic surprises – the second climax of the Dies irae gains greater force following a rather subdued first one, and the Lacrymosa builds persuasively. Despite the encomia lavished on this recording (and not only from English critics who instintively tend to worship Beecham; "marvelous" – Gramophone; "remarkable" – Classicalcdreview; "a touchstone performance – dramatically perfect" – Tepper), I question whether it serves as a complete realization. But as a purely musical take it works quite well on its own terms– and perhaps is especially suitable for our superficial times and increasingly brief attention spans.

- Eugene Ormandy, Philadelphia Orchestra, Temple University Choirs, Cesare Valletti (1964, Columbia LPs, 78')

The LP box proclaimed this to be: "A thrilling recording that captures the blaze and glory, the hushed victory of the Berlioz Requiem … a hi-fi sound spectacular … thrilling … stupendous." If only! Those enticed by the euphoric hype took home a merely decent, yet generally dutiful, reading that warrants few of the publicists' superlatives. As with much of his vast Columbia catalog, Ormandy's leadership is undeniably idiomatic but barely inspirational and thus falls considerably short of this work's full potential. While the calmer sections fare well, the Tuba mirum brass fail to startle and are too closely synchronized to suggest much sense of space, the Lacrymosa is drained of its edgy drive and the operatic Sanctus solo suggests more passion than peace. Yet there's a fascinating divide – the famed orchestra's smooth, blended, relaxed sound is evident from the first notes and is sustained throughout (and later anchored by a remarkably reverberant bass drum), in contrast to the chorus, which comes across as comparatively unpolished (in the best sense of eager enthusiasm). Even if unintended, the disparity between instrumental and vocal textures might suggest a philosophical tension between abstract infinite constancy and specific human need, reflective of heaven versus earth.

- Maurice Abravanel, Utah Symphony Orchestra, University of Utah Civic Chorale and A Capella Choir, Charles Bressler (1969, Vanguard LPs, 82')

At long last, 132 years after the premiere,

technology finally caught up to the Requiem with its first recording in surround sound, adding a dimension of tangible depth to the frontal spread of stereo. Yet its impact at the time was marginal. Admittedly it served as a spectacular demonstration piece for Vanguard's launch of the first quadraphonic home playback process, but those hi-fi buffs willing to invest in the essential equipment upgrades were daunted by an ultimately destructive marketing war that quickly ensued among incompatible media and formats and soon relegated quad to a failed gimmick with scant product. When considered as a standard stereo rendition, the Abravanel deserves far more credit than it generally receives. The choruses (despite their presumably amateur status) are beautifully blended and focused, the pacing is sensitive, if not especially inspired, the ambiance (recorded in the Mormon Tabernacle) is rich and natural, the brass is vividly prominent and the fidelity is effective (although it suddenly becomes thin and shrill for the Lacrymosa). Only recently has SACD and DVD technology revived interest in home surround sound (which, alas I am not equipped to enjoy). In a Classicstoday.com review, David Hurwitz termed a quad reissue of the Abravanel (in addition to slamming it as a "mediocre rendition," with which I respectfully disagree) thusly: "orchestras and choirs sound fuzzy while the four brass bands blast through each speaker as though individually miked in a separate dead acoustic, resulting in a totally artificial and unmusical falsification of the true sound of the piece." Perhaps a safer recommendation for a multi-channel Requiem recording is the widely-admired 1969 Davis/LSO (immediately below) reissued on Pentatone – although mixed down to two channels at the time, the original multi-track elements enabled modern engineers to reconstitute a reportedly convincing surround-sound atmosphere.

technology finally caught up to the Requiem with its first recording in surround sound, adding a dimension of tangible depth to the frontal spread of stereo. Yet its impact at the time was marginal. Admittedly it served as a spectacular demonstration piece for Vanguard's launch of the first quadraphonic home playback process, but those hi-fi buffs willing to invest in the essential equipment upgrades were daunted by an ultimately destructive marketing war that quickly ensued among incompatible media and formats and soon relegated quad to a failed gimmick with scant product. When considered as a standard stereo rendition, the Abravanel deserves far more credit than it generally receives. The choruses (despite their presumably amateur status) are beautifully blended and focused, the pacing is sensitive, if not especially inspired, the ambiance (recorded in the Mormon Tabernacle) is rich and natural, the brass is vividly prominent and the fidelity is effective (although it suddenly becomes thin and shrill for the Lacrymosa). Only recently has SACD and DVD technology revived interest in home surround sound (which, alas I am not equipped to enjoy). In a Classicstoday.com review, David Hurwitz termed a quad reissue of the Abravanel (in addition to slamming it as a "mediocre rendition," with which I respectfully disagree) thusly: "orchestras and choirs sound fuzzy while the four brass bands blast through each speaker as though individually miked in a separate dead acoustic, resulting in a totally artificial and unmusical falsification of the true sound of the piece." Perhaps a safer recommendation for a multi-channel Requiem recording is the widely-admired 1969 Davis/LSO (immediately below) reissued on Pentatone – although mixed down to two channels at the time, the original multi-track elements enabled modern engineers to reconstitute a reportedly convincing surround-sound atmosphere.

- Colin Davis, London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Wandsworth School Boys' Choir, Ronald Dowd (1969, Philips LPs, 91')

Hailed as the preeminent Berlioz exponent of his era,

Davis leads a straightforward but wholly effective reading that runs a full emotional gamut. The required adult choir is augmented with the tender innocence of children's voices to evoke a world free of adult corruption even though they all become swept up in the same cataclysm of cowering sinners, with thundering Dies irae drums and braying brass so powerful as to drown out all mankind with a dire warning of ultimate divine retribution. Although his tempos tend to be slower than Berlioz specified, Davis's reading seems idiomatic – carefully prepared, well-executed and shorn of the interpretive gloss that can either enhance or detract, and so for that very reason it may strongly appeal to those who seek just the music while disappointing those who prefer more personalized involvement. Davis's approach recalls Schonberg's description of Berlioz's own conducting, by which he sought pure sound and steady but supple rhythms, and Carse's report of Berlioz's constant attention to color and texture that led him to insist upon sectional rehearsals and precise placement of instrumentalists on the concert platform so as to achieve proper projection and balance. Even so, for me the tenor here is a bit too ardent and the pacing a bit too relaxed. A 2012 re-recording (LSO Live CD) is even more expansive, clocking in at 94 minutes; alas, it was one of Davis's very last concert appearances.

Davis leads a straightforward but wholly effective reading that runs a full emotional gamut. The required adult choir is augmented with the tender innocence of children's voices to evoke a world free of adult corruption even though they all become swept up in the same cataclysm of cowering sinners, with thundering Dies irae drums and braying brass so powerful as to drown out all mankind with a dire warning of ultimate divine retribution. Although his tempos tend to be slower than Berlioz specified, Davis's reading seems idiomatic – carefully prepared, well-executed and shorn of the interpretive gloss that can either enhance or detract, and so for that very reason it may strongly appeal to those who seek just the music while disappointing those who prefer more personalized involvement. Davis's approach recalls Schonberg's description of Berlioz's own conducting, by which he sought pure sound and steady but supple rhythms, and Carse's report of Berlioz's constant attention to color and texture that led him to insist upon sectional rehearsals and precise placement of instrumentalists on the concert platform so as to achieve proper projection and balance. Even so, for me the tenor here is a bit too ardent and the pacing a bit too relaxed. A 2012 re-recording (LSO Live CD) is even more expansive, clocking in at 94 minutes; alas, it was one of Davis's very last concert appearances.

- Leonard Bernstein, Orchestre Philharmonique et Choeurs de Radio France, Orchestre National de France, Stuart Burrows (1975, Columbia LPs, 87')

Unlike Bach, Beethoven and Brahms, Berlioz was still a relative youth when he wrote his Requiem,

and so it would seem a natural fit for one of our most dynamic conductors. This recording (in the Invalides with French forces) came at the very end of Bernstein's NY Philharmonic Columbia contract during a transitional international odyssey prior to devoting the rest of his recording career to concerts released by DG. Perhaps due to his flamboyant gesticulation Bernstein's conducting has been termed theatrical, which can imply artifice. But here every voice, every instrument, every note seems charged with sincere and transcendent feeling, inspired by Bernstein's ecstatic vision. Reportedly recorded quadraphonically, it never was released in that format but the sonic quality of the stereo version is superlative, with rich detail and staggeringly intense climaxes, yet always musical and thoroughly convincing. Hearing this astounding achievement is a draining experience in which you wouldn't want to indulge too often, but for me it fully captures the bold spirit and unabashed passion of the young visionary composer.

and so it would seem a natural fit for one of our most dynamic conductors. This recording (in the Invalides with French forces) came at the very end of Bernstein's NY Philharmonic Columbia contract during a transitional international odyssey prior to devoting the rest of his recording career to concerts released by DG. Perhaps due to his flamboyant gesticulation Bernstein's conducting has been termed theatrical, which can imply artifice. But here every voice, every instrument, every note seems charged with sincere and transcendent feeling, inspired by Bernstein's ecstatic vision. Reportedly recorded quadraphonically, it never was released in that format but the sonic quality of the stereo version is superlative, with rich detail and staggeringly intense climaxes, yet always musical and thoroughly convincing. Hearing this astounding achievement is a draining experience in which you wouldn't want to indulge too often, but for me it fully captures the bold spirit and unabashed passion of the young visionary composer.

- Paul McCreesh, Gabrieli Players & Consort, Wroclaw Philharmonic Choir & Orchestra, Robert Murray (2011, Signum Classics CD, 89')

Since the Bernstein release, there have been at least a dozen recordings of the Berlioz Requiem, each attracting the usual gamut of critical praise and barbs, but 2011 brought the first to apply the full breadth of period practice. Among these, as outlined in the conductor's liner notes, are pronunciation in French (rather than the customary Italianate) Latin (softening the sound of some consonants and vowels – "coeli" becomes SEE-lee rather than CHAY-lee), the use of historical brass and timpani (high and low horns in different keys rather than modern ones in F, natural trumpets for an open sonority in fanfares, narrow-bore trombones for cleaner attacks, ophicleides in lieu of the more refined sound of tubas, and drumsticks with the dried sponge heads which Berlioz specified in the score), applying early 19th century bowing, articulation and phrasing to the strings (most of which were modern instruments), and reducing the choirs to half their total size for the more modest movements, all in order to convey the composer's extraordinary ear for color. Theory aside, the result boasts some unusually distinctive textures and closely adheres to the score, with an especially atmospheric Quid sum miser, a smooth Sanctus with an ethereal tenor placed in a far-off gallery and a Hosanna that deliberately minimizes diction in compliance with the score's instruction to "sustain the notes well and smoothly without emphasizing individual notes." Others have praised this release to the heights and rank it above all others, but I miss the sheer sense of visceral excitement and infectious attitude of some of its esteemed predecessors. Even so, the singing, playing and recording are all exceptional and it undeniably deserves to be cherished as our most accurate depiction of the sheer sonority Berlioz intended (at least to the extent possible with two channels within the confines of a typical home listening room).

Nearing the very end of his life, Berlioz wrote that if all but one of his scores were threatened with destruction, he would beg mercy for the Requiem. Thanks in large part to its recordings, the Berlioz Requiem is in no danger of ever being lost or forgotten.

|

![]() As always, I'll accept both credit and blame for the opinions and musical judgments not otherwise attributed, and I gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to the following sources for the information, quotations and references in this article (* signifies a primary source):

As always, I'll accept both credit and blame for the opinions and musical judgments not otherwise attributed, and I gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to the following sources for the information, quotations and references in this article (* signifies a primary source):

- * Barzun, Jacques: Berlioz and His Century – An Introduction to the Age of Romanticism (Little, Brown, 1949)

- * Barzun, Jacques: notes to the Scherchen LP sets (Westminster XWN 2227 [mono] or WST 201 [stereo], 1958)

- * Berlioz, Hector: Memoirs of Hector Berlioz from 1803 to 1865, annotated and revised by Ernest Newman (Knopf, 1932)

- Braunstein, Joseph: notes to the Abravanel/Utah LP set (Vanguard VSQ 30006/7, 1969)

- Broderick, Amber: "Hector Berlioz's Romantic Interpretation of the Roman Catholic Requiem Tradition" (Masters Thesis, Bowling Green State University, 2012)

- Brooker, Leslie G. S.: notes to the Hollenbach/Rochester LP set (Columbia Entre EL-53, 1954)

- * Burk, John: "Historical and Descriptive Essay" in the Munch/Boston LP set (RCA Soria LDS 6077, 1959)

- * Cairns, David: "The Grand Messe des Morts and the Absence of God" (lecture delivered at Gresham College, June 26, 2012 (audio file and transcript available at: http://www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/the-grande-messe-des-morts-and-the-absence-of-god)

- * Cairns, David: Berlioz – Volume 2: Servitude and Greatness, 1832-1869 (University of California Press, 1999)

- Cairns, David: notes to the Davis/LSO LP set (Philips 6500 024/5)

- Carse, Adam: History of Orchestration (Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1925)

- Davis, Colin: "Why Berlioz?" notes to his Les Troyens LP set (Philips 6709 002, 1970)

- * Del Mar, Norman: Conducting Berlioz (Carendon Press, 1997)

- Engel, Carl: Berlioz, in Elie Siegmeister, ed.: Music Lover's Handbook (William Morrow and Company, 1943)

- Ferchault, Guy: notes to the Munch/Bavarian LP set (DG 2707 032, 1967)

- Hadow, W. H.: "Berlioz" in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Grove, 1904)

- * Holman, D. Kern: Berlioz (Harvard University Press, 1989)

- * Jones, Nick: notes to the Shaw/Atlanta CD set (Telarc CD-80109, 1985)

- Kluge, Andreas: notes to Bernstein LP set (Columbia M2 32402, 1976)

- Lang, Paul Henry: Music in Western Civilization (Norton, 1941)

- Lawrence, Robert: "Berlioz and Four Brass Bands," Saturday Review of Literature, October 30, 1948 (reprinted at www.hberlioz.com/others/RLAwrence1948.htm)

- Lawrence, Robert: notes to the Ormandy/Philadelphia LP set (Columbia M2S 730, 1964)

- * Locke, Ralph: The Religious Works, in Peter Bloom, ed.: Cambridge Companion to Berlioz (Cambridge University Press, 2000)

- MacDonald, Hugh: "Berlioz," in New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Grove, 1980)

- MacDonald, Hugh: notes to the Lewis/Washington Missa Solemnis CD (Koch 3-7204-2, 1994)

- McCreesh, Paul: notes to his CD set (Signum Classics SIGCD 280, 2011)

- Mellers, Wilfred: Man and His Music, Part III – The Sonata Principle (Schocken, 1962)

- Munch, Charles: notes to the Munch/Boston LP set (RCA Soria LDS 6077, 1959)

- Morgenstern, Sam (ed.): Composers on Music (Pantheon, 1956)

- Robert, Frédéric: notes to the Dondeyne/Paris LP of the Grande Symphonie Funèbre et Triomphale (Westminster WST 14066, 1958)

- Savini, Michele: notes to the Mitropoulos CD (Arkadia CDHP 562.2, 1992)

- Scholes, Percy: The Oxford Companion to Music, 9th Edition (Oxford, 1955)

- Schonberg, Harold: Lives of the Great Composers (Norton, 1981)

- Schonberg, Harold: The Great Conductors (Simon & Schuster, 1967)

- Shaw, Bernard: The Great Composers – Reviews and Bombardments (University of California, 1978)

- Spaeth, Sigmund: A Guide to the Great Orchestral Music (Modern Library, 1943)

- Steinberg, Michael: Choral Masterworks: A Listener's Guide (Oxford, 2005)

- * Tepper, Matthew: "Tempo, Style, and Options in Modern Performances of Hector Berlioz's Grande Messe des Morts, Op. 5" (Masters' Thesis, University of Minnesota, 1983) (available at: http://home.earthlink.net/~oy/toc.htm)

William Blake: The Last Judgment (1808) |

![]()

Copyright 2016 by Peter Gutmann

copyright © 1998-2016 Peter Gutmann. All rights reserved.