|

The creative process of most composers tends toward extremes. For a rare few (Bach, Mozart, Schubert) music seemed to pour out instinctively and naturally, fully formed. Others (Beethoven, Wagner) labored mightily, incessantly honing their work until finally deemed worthy of release. Felix Mendelssohn's 1833 Italian Symphony was something else – a brilliant masterpiece as first conceived, but that became weaker the more he revised it.

Mendelssohn at age 20 – portrait by James Warren Childe |

The Italian is designated as the fourth of Mendelssohn's five symphonies, but the numbering is confusing. By age 15, when Mendelssohn wrote his first symphony to receive a formal number, it already followed a dozen others for strings that, while highly accomplished, were intended for private performance in family musicales and never were issued. Next came # 5, the formal "Reformation," written in 1829–30 for a Lutheran doctrinal conference, which he suppressed after a single performance; then #3 (the "Scottish"), on which he labored from 1829 until its premiere in 1842; then # 4 (the "Italian"); and finally # 2 ("Lobgesang" – Hymn of Praise), actually the prelude to an 1840 festival cantata. The familiar numbering (and corresponding opus numbers) reflect their order of publication (two posthumously), while in order of conception they would be ordered as #s 1, 5, 3, 4 and 2, and in order of first performance as #s 1, 5, 4, 2 and 3.

![]() As expected of most young men of means at the time, after completing his formal education Mendelssohn embarked on a "Grand Tour" to directly absorb the other cultures of Europe. First in 1829 came Britain, where he performed to great acclaim and traveled to the North, which inspired his restlessly moody "Hebrides" Overture and his deeply-felt, tautly-integrated "Scottish" Symphony. Next was his Italian excursion, from March 1830 through July 1831, which would kindle his most popular work of all. He was guided and enthused by the Italienische Reise (Italian Journey) of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe,

As expected of most young men of means at the time, after completing his formal education Mendelssohn embarked on a "Grand Tour" to directly absorb the other cultures of Europe. First in 1829 came Britain, where he performed to great acclaim and traveled to the North, which inspired his restlessly moody "Hebrides" Overture and his deeply-felt, tautly-integrated "Scottish" Symphony. Next was his Italian excursion, from March 1830 through July 1831, which would kindle his most popular work of all. He was guided and enthused by the Italienische Reise (Italian Journey) of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe,

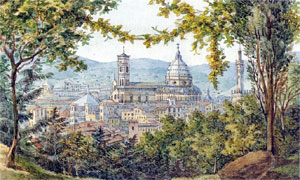

Watercolor by Mendelssohn: Florence |

Jonathan Kramer notes that throughout his visit Mendelssohn rarely mentioned the people and was curiously untouched by their politics, culture or society – and even their music. At first he seemed disillusioned: "The people are mentally enervated and apathetic. They have a religion which they do not believe, a pope and a government which they ridicule, a historical and heroic past which they disregard. It is then no marvel that they do not delight in art, for they are indifferent to all that is serious." Rather, he took inspiration directly from the natural sites he encountered. Thus he wrote of the "exhilarating impression made on me by the first sight of the plains of Italy. I hurry from one enjoyment to another hour by hour and constantly see something novel and fresh." He asked: "Why should Italy insist on being the land of art while in reality it is the land of nature?"

Eventually his disenchantment abated and he came to embrace the Italian pace of life, so different from the custom in Germany: "I imagined that my very first impression of Italy would be explosive, an impact of tremendous animation. So far it has not been like that; instead there is a warmth, mildness and happiness, a sense of joyous well-being spread over everything that is quite indescribable."

Watercolor by Mendelssohn: Amalfi |

It is that very melding of natural beauty and effortless abandon within a context of intellectual curiosity and exploration that suffused his nascent work, which he considered a "fair weather symphony," as opposed to the "mists and melancholy" of his prior Scottish overture and symphony. In February 1831 he wrote from Rome: "I have once more begun to compose with fresh vigor and the Italian symphony makes rapid progress. It will be the most sportive piece I have yet written." And in late April: "If I remain in my present mood I might even finish the Italian symphony in Italy."

He didn't.

Watercolor by Mendelssohn: Lake Como |

Mendelssohn completed his new symphony on March 13, 1833, embarked for England and led the premiere on May 13 in a London concert that seems a marathon by current standards, as it also included overtures by Pixis and Weber, three Mozart and Meyerbeer arias, a Rossini duet, Haydn's Symphony # 104, Mozart's Piano Concerto in d minor [# 20] and a De Beriot violin concerto. It was a huge triumph – Mendelssohn wrote home that "people say that it was the best concert the Society has ever given." The Harmonium accurately predicted that the symphony, proudly billed as "expressly composed for this Society," "will endure for the ages" but expressed concern that it was "so full of brilliant conceptions … and so rapid their succession that it would be a hopeless attempt to analyze it without either having heard it several times or having the score to refer to." Fortunately, in our age of electronics we suffer no comparable hardship.

![]() The Italian Symphony, as we have come to know it, comprises the standard four symphonic movements yet has little need of formal analysis, as it radiates irresistible joy and affection, even while comfortably nestled within a customary structure. Although commentators have attributed each movement to an aspect of Mendelssohn's fascination with his travels, Mendelssohn himself, following frequent references to an "Italian symphony" in his correspondence from abroad, later avoided the title so as to stress its essence as a true symphony rather than a suite of tonal landscapes. And as others have pointed out, while the work may have been conceived and sketched in Italy, it was developed and finished only later back home.

The Italian Symphony, as we have come to know it, comprises the standard four symphonic movements yet has little need of formal analysis, as it radiates irresistible joy and affection, even while comfortably nestled within a customary structure. Although commentators have attributed each movement to an aspect of Mendelssohn's fascination with his travels, Mendelssohn himself, following frequent references to an "Italian symphony" in his correspondence from abroad, later avoided the title so as to stress its essence as a true symphony rather than a suite of tonal landscapes. And as others have pointed out, while the work may have been conceived and sketched in Italy, it was developed and finished only later back home.

I – Allegro vivace – Perhaps taking a cue from Beethoven's Eighth,

The bounding theme of the first movement:

|

II – Andante con moto – Most commentators

|

The introduction and theme of the Andante: |

III – Con moto moderato –

|

The themes of the minuet and trio: |

IV – Saltarello – Presto – There's no need to speculate as to the spur for the breathless, inexhaustibly energetic finale. Mendelssohn wrote of his fascination with the wild dancing during Roman carnivals, "of being pelted with confetti … by young ladies he scarcely knew," and the movement is a blending of two vigorous Italian peasant dances, both of which feature a rapid juxtaposition of duple and triple rhythms.

|

The themes of the saltarello and tarantella: |

![]() Despite universal acclaim at its premiere, the Italian Symphony failed to please one of the most prominent and respected musicians and critics of its time – Mendelssohn himself, who never thought it worthy of publication.

Despite universal acclaim at its premiere, the Italian Symphony failed to please one of the most prominent and respected musicians and critics of its time – Mendelssohn himself, who never thought it worthy of publication.

The "mature" Mendelssohn (1846, age 37) – painting by Edward Magnus |

Critics have long wondered why Mendelssohn, although a habitually incessant reviser, felt compelled to alter and suppress such a fine work, and especially the finale. Thus Harrison: "To this day [in 1964] no one has yet discovered where the flaws in this wild dance … exist, so perfectly constructed, imagined and orchestrated is the music in every detail." Seaton suggests that Mendelssohn's compulsion reflected his intense self-criticism and self-doubt, which Adam Carse relates to his routine of constantly revising and polishing scores even after publication – indeed, he only considered his Scottish Symphony, begun before the Italian, to be complete in 1842.  Tovey attributed such dissatisfaction more generally to the laws of human growth – a common assumption that mature perspective invariably improves the impulses of youth. In that sense, the result invokes Scott Goddard's comparison of the never-revised Hebrides Overture ("a flash of inspiration immediately formed into a work or art") with the heavily-reworked Scottish Symphony ("changed from youthful intensity and ebullience into a deeper and more cautious expressiveness, ... by careful nurturing of memories overlaid by many intervening experiences"). Charles Burr, though, suggests a simpler rationale for Mendelssohn's frustration with his attempts to improve the Italian – it already was so perfect that it defied revision that a less accomplished piece might invite, if not demand.

Tovey attributed such dissatisfaction more generally to the laws of human growth – a common assumption that mature perspective invariably improves the impulses of youth. In that sense, the result invokes Scott Goddard's comparison of the never-revised Hebrides Overture ("a flash of inspiration immediately formed into a work or art") with the heavily-reworked Scottish Symphony ("changed from youthful intensity and ebullience into a deeper and more cautious expressiveness, ... by careful nurturing of memories overlaid by many intervening experiences"). Charles Burr, though, suggests a simpler rationale for Mendelssohn's frustration with his attempts to improve the Italian – it already was so perfect that it defied revision that a less accomplished piece might invite, if not demand.

Mendelssohn's revised versions of all but the first movement were published only in 1997. The following year Deutsche Grammophon issued a "world premiere" recording in which the enterprising John Eliot Gardiner performed them with the Vienna Philharmonic (along with the well-known original versions for comparison). Now that Mendelssohn's revisions are extant, we can compare them to the original. As a general matter, Todd observes that Mendelssohn's (and most other composers') revisions tend to entail compression, removal of redundant material and tightening of the musical argument, whereas few of the Italian emendations involved significant attenuation, but rather lengthen each movement, along with adjustments to subtle details of melodic contour, scoring and the harmonic vocabulary. Although Tovey hails the original orchestration as "unsurpassed for beauty and accuracy," Günter-Klein adds that the net result of the changes was to lighten the instrumentation and bring the structure closer to traditional form. Edward Greenfield reacted more viscerally "with astonishment that so meticulous and discriminating a composer as Mendelssohn could in his revision have actually undermined the inspiration of the original" to produce a version "relatively bland and conventional."

Opening of the Andante (oboe parts from the autographs) – original (top) v. revision (bottom) |

Turning to specifics, the most striking alteration to the second movement is immediately apparent in the flattening of the melody toward the end of the theme. As Todd notes, the suppleness and grace of the original cede to a more modal quality. At the same time, Mendelssohn brightens the scalar "walking bass" accompaniment with skips. He further pads transitions with extra measures that add atmosphere at the expense of momentum. Even so, his expansion of the wind-dominated central section generates some lovely melodic touches. For his revision of the third movement, Mendelssohn formally renamed it "minuet and trio. " (The original was identified only by its tempo – Con moto moderato (with moderate motion), which he replaced with the more expressive Con moto grazioso (with graceful motion).) He also substantially altered the structure – both halves of the minuet are repeated, not just the first, and the trio is linked to the da capo return of the minuet by an elaborate bridge passage that displays an extended harmonic excursion that seems rather diffuse but which Günter-Klein hails as representing an entirely new compositional technique. Here, too, the melodies are evened out and dotted figures are smoothed into runs of uniform eighth notes. Yet in a lovely new ending the violins gently soar toward the height of their range. The tarantella section of the finale is extended, with interest added through string pizzicatos but the movement tends to ramble and the overall weightier timbre owes more to German mysticism than the crisp, penetrating Mediterranean sun.

![]() Mendelssohn's reputation followed an unusual trajectory, as traced by Todd. Robert Schumann, arguably the most respected critic of the era, proclaimed him "the Mozart of the 19th century" and "the first musician of our time ... who recognizes most clearly the opposition of our age and who reconciles it." Amplifying that view, David Hall explains that Mendelssohn achieved an ideal balance between the romantic impulsiveness of his melodies and the cohesion, precision and finely-honed workmanship of his classical structures, abetted by the efficiency and clarity of his instrumentation. His early death in 1847 at age 38 was mourned as an international tragedy and "the eclipse of music." But then in the throes of Wagnerism his orthodox tendencies became incongruous, at least in the eyes of progressives. Thus in 1875 Frederich Neitzche disdained his "serene beauty" compared to "the rugged energy, the subtle thoughtfulness and morbid world-weariness of other composers." Yet in England his outlook resonated with Victorian mores – Grove argued: "Surely there is enough of conflict and violence in life and in art. When we want to be made unhappy we can turn to others. … It is well in these agitated modern days to be able to point to one perfectly balanced nature in whose … music … all is at once refined, … pure, brilliant and solid. For the enjoyment of such shining heights of goodness we may well for once forgo the depth of misery and sorrow."

Mendelssohn's reputation followed an unusual trajectory, as traced by Todd. Robert Schumann, arguably the most respected critic of the era, proclaimed him "the Mozart of the 19th century" and "the first musician of our time ... who recognizes most clearly the opposition of our age and who reconciles it." Amplifying that view, David Hall explains that Mendelssohn achieved an ideal balance between the romantic impulsiveness of his melodies and the cohesion, precision and finely-honed workmanship of his classical structures, abetted by the efficiency and clarity of his instrumentation. His early death in 1847 at age 38 was mourned as an international tragedy and "the eclipse of music." But then in the throes of Wagnerism his orthodox tendencies became incongruous, at least in the eyes of progressives. Thus in 1875 Frederich Neitzche disdained his "serene beauty" compared to "the rugged energy, the subtle thoughtfulness and morbid world-weariness of other composers." Yet in England his outlook resonated with Victorian mores – Grove argued: "Surely there is enough of conflict and violence in life and in art. When we want to be made unhappy we can turn to others. … It is well in these agitated modern days to be able to point to one perfectly balanced nature in whose … music … all is at once refined, … pure, brilliant and solid. For the enjoyment of such shining heights of goodness we may well for once forgo the depth of misery and sorrow."

1837 lithograph by Friedrich Jantzen |

![]() Schonberg credits Mendelssohn as the first dominating German podium force, an all-encompassing musician with impeccable taste whose personality was reflected not only in his music but in his style of conducting, which was elegant, polished and prepared through patience, politeness and small gestures. Schumann marveled: "With his eye he anticipated and communicated every meaningful turn and nuance from the most delicate to the most robust, an inspired leader … in comparison to those conductors who threaten with their scepters to thrash the score, the orchestra and even the audience." Hector Berlioz observed: "His every remark is calm and pleasant, and his attitude is much appreciated by those who, like myself, know how rare such patience is." Joseph Joachim hailed his "almost unnoticeable but extremely lively gestures … to correct little errors with the flick of his finger." Yet even while Grove contended that Mendelssohn strictly adhered to authors' indications in a score, Hans von Bülow noted his "elastic sensitivity" and "wonderful nuances of color." (Not unexpectedly, Wagner thought him superficial.) From all this, Schonberg surmises that Mendelssohn's own approach to conducting was lively and suave, with emphasis on steady rhythm and control, and a penchant for fast but steady tempos. That, in turn, seems fully congruent with his style at the keyboard, for which he was deeply famous and admired, described as favoring very quick tempos but stamped with beauty and nobility (Clara Schumann), extraordinary for its life and crispness (Joachim), having a light wrist touch, clear phrasing and sparing use of the pedals (Otto Goldschmidt) and overall "astonishing dexterity, lightness and elegance" (a review of an 1827 recital).

Schonberg credits Mendelssohn as the first dominating German podium force, an all-encompassing musician with impeccable taste whose personality was reflected not only in his music but in his style of conducting, which was elegant, polished and prepared through patience, politeness and small gestures. Schumann marveled: "With his eye he anticipated and communicated every meaningful turn and nuance from the most delicate to the most robust, an inspired leader … in comparison to those conductors who threaten with their scepters to thrash the score, the orchestra and even the audience." Hector Berlioz observed: "His every remark is calm and pleasant, and his attitude is much appreciated by those who, like myself, know how rare such patience is." Joseph Joachim hailed his "almost unnoticeable but extremely lively gestures … to correct little errors with the flick of his finger." Yet even while Grove contended that Mendelssohn strictly adhered to authors' indications in a score, Hans von Bülow noted his "elastic sensitivity" and "wonderful nuances of color." (Not unexpectedly, Wagner thought him superficial.) From all this, Schonberg surmises that Mendelssohn's own approach to conducting was lively and suave, with emphasis on steady rhythm and control, and a penchant for fast but steady tempos. That, in turn, seems fully congruent with his style at the keyboard, for which he was deeply famous and admired, described as favoring very quick tempos but stamped with beauty and nobility (Clara Schumann), extraordinary for its life and crispness (Joachim), having a light wrist touch, clear phrasing and sparing use of the pedals (Otto Goldschmidt) and overall "astonishing dexterity, lightness and elegance" (a review of an 1827 recital).

All of this seems especially apt as interpretive guidance for the Italian Symphony, and seemingly should apply with full force to its recordings, which, in addition to Mendelssohn's trademark clarity and balance, ideally should project the sheer exuberance of youth, an innocent fascination with exotic adventure, and a joyful acceptance of all the wonderous splendors of the world. With that in mind …

![]() The headnotes below list the conductor and orchestra, followed in parentheses by the year of recording, original label and format, current label and format, and overall timing. For the sake of meaningful comparison of timings, I'm indicating the repeats omitted ("F" for the first movement exposition, "M" for the first part of the minuet and "T" for the first part of the trio) and approximating the total time had they been taken. I had hoped to provide a baseline by averaging the timings of "historically-informed" recordings (Goodman/Hanover Band, Norrington/London Classical Players, Weil/Tafelmusik, Bruggen/Orchestra of the 18th Century, and Mackerras/Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment), but that proved elusive, as there was wide variance among them: the first movement ranged from 10:25 to 11:13, the second from 5:08 to 6:23, the third from 5:34 to 6:43, the fourth from 5:15 to 6:00, and the totals from 26:50 to 29:03, albeit clustered toward the higher end of that span.

The headnotes below list the conductor and orchestra, followed in parentheses by the year of recording, original label and format, current label and format, and overall timing. For the sake of meaningful comparison of timings, I'm indicating the repeats omitted ("F" for the first movement exposition, "M" for the first part of the minuet and "T" for the first part of the trio) and approximating the total time had they been taken. I had hoped to provide a baseline by averaging the timings of "historically-informed" recordings (Goodman/Hanover Band, Norrington/London Classical Players, Weil/Tafelmusik, Bruggen/Orchestra of the 18th Century, and Mackerras/Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment), but that proved elusive, as there was wide variance among them: the first movement ranged from 10:25 to 11:13, the second from 5:08 to 6:23, the third from 5:34 to 6:43, the fourth from 5:15 to 6:00, and the totals from 26:50 to 29:03, albeit clustered toward the higher end of that span.

- Stanley Chapple, Aeolian Orchestra (1925, Aeolian Vocalion 78s, 25:00 + F = 28:10)

Coming at the end of the acoustical era, this first complete recording of the Italian was led by the British house conductor of the Vocalion label, a subsidiary of the Aeolian piano company.  A mere 24 at the time, Chapple would emigrate to America, where he co-founded Tanglewood, led the Seattle Symphony for 20 years and became dean of the Washington University School of Music. His style is hard to pin down, as his other recordings of the time range from a thrilling Grieg Piano Concerto with Maurice Cole, a somewhat outgoing Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto # 1 with Vassily Sapellnikoff (who had toured the work with the composer and reportedly was his preferred interpreter), and rather bland Bach and Mozart violin concerti with the tempermental romantic Jelly d'Aranyi. While it's tempting to attribute these vastly different approaches to deference to the predilections of his soloists, when left to his own Cole displays a comparably wide range within the Italian. Thus the first movement is patiently-paced, steady, dutiful and rather rigid, with level dynamics and little hint of grace or subtlety. The Andante, though, darts past at an uncommonly brisk 4:40 (compared to a normal 6 minutes or so), perhaps to fit onto a single side, yet even at this pace the thick recorded textures prevent it from sounding agile. Even so, the tubas, substituted for the basses, as was routinely done to overcome the tendency of the acoustical mechanism to distort deep bass, create an unintended contrast of textures by rasping away brusquely in the passages that should be wholly dominated by glossy strings, for which occasional portamento only partly compensates. The third movement, too, flits by somewhat faster than is customary (and, unusual for early recordings, includes both the minuet and trio repeats). The finale, though, adds nearly a minute to the usual pace and seems a bit too self-conscious and solemn to effectively convey the wild abandon of frenzied dances. After citing purported defects and miscalculations in Mendelssohn's orchestration (for overly prominent brass and timpani of varying intensity, undoubtedly artifacts of the deficient fidelity and reduced forces mandated by the acoustical process), Gramophone's reviewer praised it as "full of interest and novelty … I have nothing but praise for a notable achievement that will, I fancy, be welcomed with acclaim by many." Clearly, it served a valid purpose in first extending this work beyond the confines of concert halls into homes, but in retrospect barely captures the essence and charm.

A mere 24 at the time, Chapple would emigrate to America, where he co-founded Tanglewood, led the Seattle Symphony for 20 years and became dean of the Washington University School of Music. His style is hard to pin down, as his other recordings of the time range from a thrilling Grieg Piano Concerto with Maurice Cole, a somewhat outgoing Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto # 1 with Vassily Sapellnikoff (who had toured the work with the composer and reportedly was his preferred interpreter), and rather bland Bach and Mozart violin concerti with the tempermental romantic Jelly d'Aranyi. While it's tempting to attribute these vastly different approaches to deference to the predilections of his soloists, when left to his own Cole displays a comparably wide range within the Italian. Thus the first movement is patiently-paced, steady, dutiful and rather rigid, with level dynamics and little hint of grace or subtlety. The Andante, though, darts past at an uncommonly brisk 4:40 (compared to a normal 6 minutes or so), perhaps to fit onto a single side, yet even at this pace the thick recorded textures prevent it from sounding agile. Even so, the tubas, substituted for the basses, as was routinely done to overcome the tendency of the acoustical mechanism to distort deep bass, create an unintended contrast of textures by rasping away brusquely in the passages that should be wholly dominated by glossy strings, for which occasional portamento only partly compensates. The third movement, too, flits by somewhat faster than is customary (and, unusual for early recordings, includes both the minuet and trio repeats). The finale, though, adds nearly a minute to the usual pace and seems a bit too self-conscious and solemn to effectively convey the wild abandon of frenzied dances. After citing purported defects and miscalculations in Mendelssohn's orchestration (for overly prominent brass and timpani of varying intensity, undoubtedly artifacts of the deficient fidelity and reduced forces mandated by the acoustical process), Gramophone's reviewer praised it as "full of interest and novelty … I have nothing but praise for a notable achievement that will, I fancy, be welcomed with acclaim by many." Clearly, it served a valid purpose in first extending this work beyond the confines of concert halls into homes, but in retrospect barely captures the essence and charm.

- Ettore Panizza, La Scala Orchestra (1931, La Voce del Padrone 78s, Pristine download and CD, 27:40 + F + M + T = 31:25)

Aptly enough, the second recording of the Italian Symphony was by an Italian conductor and an Italian orchestra.  An assistant to Toscanini at La Scala for a decade, Panizza was best known for Italian opera and apparently shone in the theater – his four live 1938-41 Met Otellos are remarkably vital, with emphatic emotional underlining fueled by the sheer visceral excitement of his proactive conducting, and a 1939 Gioconda turns the normally engaging "Dance of the Hours" from sweet, teasing suspense into a frantic wild fling. While his studio work tends to be far more sedate, among his few orchestral recordings he seemed to have a special affinity for Mendelssohn, with a 1928 Hebrides Overture that builds convincingly and a Midsummer Night's Dream "Wedding March" (the eighth-side filler for his Italian Symphony) that smoothly blends its complementary noble and lyric sections. As for his Italian, its mellow pacing and surprisingly careless ensemble that blurs many rapid passages challenge the pleasure otherwise generated by its fine instrumental balances (although the timpani are inaudible), strong accents, lovely phrasing and full dynamics (assuming the last weren't artificially enhanced by Pristine's digital processing). A few curious touches – Panizza slows down to underscore the transition points of the Andante, adds an unusual flavor to the opening minuet theme by exaggerating the separation between notes, and speeds up an otherwise stodgy finale for the tarantella, although even then the deliberate tempo of the rest suppresses much of its underlying roiling energy. Overall, Panizza emphasizes formal classical poise and maturity over romantic ardor – not necessarily an invalid approach, but one that partly denies the fundamental inspiration.

An assistant to Toscanini at La Scala for a decade, Panizza was best known for Italian opera and apparently shone in the theater – his four live 1938-41 Met Otellos are remarkably vital, with emphatic emotional underlining fueled by the sheer visceral excitement of his proactive conducting, and a 1939 Gioconda turns the normally engaging "Dance of the Hours" from sweet, teasing suspense into a frantic wild fling. While his studio work tends to be far more sedate, among his few orchestral recordings he seemed to have a special affinity for Mendelssohn, with a 1928 Hebrides Overture that builds convincingly and a Midsummer Night's Dream "Wedding March" (the eighth-side filler for his Italian Symphony) that smoothly blends its complementary noble and lyric sections. As for his Italian, its mellow pacing and surprisingly careless ensemble that blurs many rapid passages challenge the pleasure otherwise generated by its fine instrumental balances (although the timpani are inaudible), strong accents, lovely phrasing and full dynamics (assuming the last weren't artificially enhanced by Pristine's digital processing). A few curious touches – Panizza slows down to underscore the transition points of the Andante, adds an unusual flavor to the opening minuet theme by exaggerating the separation between notes, and speeds up an otherwise stodgy finale for the tarantella, although even then the deliberate tempo of the rest suppresses much of its underlying roiling energy. Overall, Panizza emphasizes formal classical poise and maturity over romantic ardor – not necessarily an invalid approach, but one that partly denies the fundamental inspiration.

- Hamilton Harty, Hallé Orchestra (1931, Columbia 78s, 22:50 + F + M + T = 26:20)

Although personally reticent and especially valued as an accompanist, when left to his own Harty inscribed some magnificently outgoing recordings among the many he cut with the Hallé Orchestra, which he led since 1920. Among these is his Italian, which is at the opposite end of the interpretive spectrum from Chapple and Panizza. What a difference a minute makes! The first movement bursts out of the gate – light, sunny and fully reflecting the joy of youthful discovery of exotic delights – and then (consistent with the score) is topped off with a final burst of speed to the finish. The finale – which beats Chapple by a minute and Panizza by a minute and a half – exhausts with driven, focused energy. The inner movements, moderately paced, provide a welcome respite. While dynamics are moderate and balances favor the violins (and the strings over all else) the sheer drive of the stirring tempos of the outer movements creates sufficient exhilaration to carry it all forward. With an eye to commercial advantage, the entire symphony was fit onto three discs, rather than the four required by Chapple and Panizza, but at the cost of splitting all but the first movement between sides (that is, II begins on side 3 and concludes on side 4, III begins on side 4 and concludes on side 5, and IV begins on side 5 and ends on side 6).

when left to his own Harty inscribed some magnificently outgoing recordings among the many he cut with the Hallé Orchestra, which he led since 1920. Among these is his Italian, which is at the opposite end of the interpretive spectrum from Chapple and Panizza. What a difference a minute makes! The first movement bursts out of the gate – light, sunny and fully reflecting the joy of youthful discovery of exotic delights – and then (consistent with the score) is topped off with a final burst of speed to the finish. The finale – which beats Chapple by a minute and Panizza by a minute and a half – exhausts with driven, focused energy. The inner movements, moderately paced, provide a welcome respite. While dynamics are moderate and balances favor the violins (and the strings over all else) the sheer drive of the stirring tempos of the outer movements creates sufficient exhilaration to carry it all forward. With an eye to commercial advantage, the entire symphony was fit onto three discs, rather than the four required by Chapple and Panizza, but at the cost of splitting all but the first movement between sides (that is, II begins on side 3 and concludes on side 4, III begins on side 4 and concludes on side 5, and IV begins on side 5 and ends on side 6).

- Serge Koussevitzky, Boston Symphony Orchestra (1935, Victor 78s, Pearl CD, 23:15 + F = 26:33)

The last of the pioneering first decade of Italian recordings  is a remarkable tour de force insofar as the orchestra manages to meet Koussevitzky's manic pace with alacrity, bringing in the first movement in under seven minutes. The rest tends toward the fast end of "normal," maintaining an overall feeling of speed while avoiding even a whiff of solemn reflection, the only slight relaxation coming with an added deceleration at the end of the trio. The strings, and especially the violins, tend to dominate the texture, all but obscuring the subtleties of the instrumentation, including the flute introduction of the saltarello theme. The ensemble throughout is superb, with the finale absolutely gripping in its riveting magnetism and sustained energy. (While the basic pulse of the finale is not all that much faster than Harty's, the detail and presence of the recording add a significant layer of visceral excitement absent from Harty's rather blurred sonics.) Some have criticized the result as superficial, but the sense of commitment is tangible and the sheer velocity creates a thrilling air of breathless excitement rarely matched ever since.

is a remarkable tour de force insofar as the orchestra manages to meet Koussevitzky's manic pace with alacrity, bringing in the first movement in under seven minutes. The rest tends toward the fast end of "normal," maintaining an overall feeling of speed while avoiding even a whiff of solemn reflection, the only slight relaxation coming with an added deceleration at the end of the trio. The strings, and especially the violins, tend to dominate the texture, all but obscuring the subtleties of the instrumentation, including the flute introduction of the saltarello theme. The ensemble throughout is superb, with the finale absolutely gripping in its riveting magnetism and sustained energy. (While the basic pulse of the finale is not all that much faster than Harty's, the detail and presence of the recording add a significant layer of visceral excitement absent from Harty's rather blurred sonics.) Some have criticized the result as superficial, but the sense of commitment is tangible and the sheer velocity creates a thrilling air of breathless excitement rarely matched ever since.

A near-hiatus of over a decade followed the Koussevitzky album. Perhaps the innocent charm of the Italian seemed out of place in a world racked with war (yet perhaps it was needed more than ever in such circumstances). Only one recording appeared during that entire interval, and from a most improbable source:

- Thomas Beecham, New York Philharmonic (1942, Columbia 78s, Sony Heritage CD, 27:15 + F = 30:00); Royal Philharmonic (1952, HMV LP, EMI CD, 29:00 + F = 32:05)

Arguably the most prominent British conductor of the time, Beecham won few plaudits from his countrymen when he deserted England for America in 1940. As recounted by Michael Gray, he signed a three-year contract with RCA Victor but before it was to have begun (and before thwarted by the Petrillo recording ban)  Columbia offered him a session with the New York Philharmonic, its flagship orchestra that was in turmoil without a permanent leader upon Barbirolli's departure. On June 13 and 15, 1942, they cut Tchaikovsky's Capriccio Italien, Sibelius's Symphony # 7, Rimsky-Korsakoff's Le Coq d'Or Suite and the Italian. Gray notes: "Facing [not only a new orchestra but] a new hall, producer, engineer and recording technique, Beecham's customary magic seemed to falter." Beecham was so dissatisfied that he sued Columbia not only to prevent publication but for $600,000 in damages for injuring his reputation. Fortunately for us, he lost and the recordings were issued. Heard today, the result may not be intensely inspired, but hardly a disaster. (The Italian was cut during the second of the two sessions, so perhaps some of the initial anxiety had worn off by then.) In 1944 Beecham returned home and, after "futile attempts at reconciliation with the musicians he had left behind in going to America," he founded a new orchestra, the Royal Philharmonic, with which he re-recorded the Italian in three sessions in December 1951 and May and June 1952. All but the Andante are considerably slower and, rather surprisingly, more tentative and stiff than in New York. The execution of the remake is more secure but its fidelity is thin and lacks the more blended atmosphere and sonic depth of the earlier version, which is sufficiently urbane without becoming self-conscious. Beecham maintains an unvarying pace throughout and by adding a full minute to the minuet and trio imposes on it a somber, reflective weight, more suggestive of lazing in the hot mid-day Mediterranean sun than eagerly exploring compelling sights. Beecham reportedly once declined to substitute the Italian in an upcoming concert, contending that he could have prepared Stravinsky's Rite of Spring in the two allotted rehearsals but would need five for the Mendelssohn. From his only recorded evidence, such an effort barely seems to show.

Columbia offered him a session with the New York Philharmonic, its flagship orchestra that was in turmoil without a permanent leader upon Barbirolli's departure. On June 13 and 15, 1942, they cut Tchaikovsky's Capriccio Italien, Sibelius's Symphony # 7, Rimsky-Korsakoff's Le Coq d'Or Suite and the Italian. Gray notes: "Facing [not only a new orchestra but] a new hall, producer, engineer and recording technique, Beecham's customary magic seemed to falter." Beecham was so dissatisfied that he sued Columbia not only to prevent publication but for $600,000 in damages for injuring his reputation. Fortunately for us, he lost and the recordings were issued. Heard today, the result may not be intensely inspired, but hardly a disaster. (The Italian was cut during the second of the two sessions, so perhaps some of the initial anxiety had worn off by then.) In 1944 Beecham returned home and, after "futile attempts at reconciliation with the musicians he had left behind in going to America," he founded a new orchestra, the Royal Philharmonic, with which he re-recorded the Italian in three sessions in December 1951 and May and June 1952. All but the Andante are considerably slower and, rather surprisingly, more tentative and stiff than in New York. The execution of the remake is more secure but its fidelity is thin and lacks the more blended atmosphere and sonic depth of the earlier version, which is sufficiently urbane without becoming self-conscious. Beecham maintains an unvarying pace throughout and by adding a full minute to the minuet and trio imposes on it a somber, reflective weight, more suggestive of lazing in the hot mid-day Mediterranean sun than eagerly exploring compelling sights. Beecham reportedly once declined to substitute the Italian in an upcoming concert, contending that he could have prepared Stravinsky's Rite of Spring in the two allotted rehearsals but would need five for the Mendelssohn. From his only recorded evidence, such an effort barely seems to show.

![]() After the War, a pair of Italian recordings appeared that presented stylistic extremes, followed in close succession by two more having relatively more mainstream approaches but with their own points of interest:

After the War, a pair of Italian recordings appeared that presented stylistic extremes, followed in close succession by two more having relatively more mainstream approaches but with their own points of interest:

- Heinz Unger, National Symphony Orchestra (London) (1945, Decca 78s, 28:50 + F = 32:20)

Unger apparently had a deep devotion to the music of Mahler, which Herman Tesler-Mabé attributes to their parallel experiences as Jews forced to assimilate, while clinging to their heritage and reconciling their conflicted identities through music. (Expelled from Berlin in 1933, Unger emigrated to Britain and eventually settled in Canada.) Perhaps that also explains his being drawn to Mendelssohn, who was born into a prominent Jewish family but at the age of seven was converted to Catholicism by his father in the hope of gaining entry into mainstream German society (although entrenched prejudice impeded his career nonetheless).

Indeed, beside Beethoven's “Eroica” Symphony, nearly all of Unger's few recordings were of Mendelssohn – the Hebrides, Athalie and Ruy Blas overtures and the Italian Symphony. He seems to embed his German roots in the first movement, which weighs in at nine minutes without the repeat – not quite Brucknerian, but far more bulky and pensive than any other I've heard. Although he accelerates the end as if to prepare for a transition to a more conventional outlook, it's just a tease, as the rest cannot escape being colored by the accumulated weight of the opening – its overcast pervades the Andante, the minuet only hints at a slight awakening and the finale cannot fully rouse – overall, a fascinating and unique, if highly eccentric, interpretation.

Indeed, beside Beethoven's “Eroica” Symphony, nearly all of Unger's few recordings were of Mendelssohn – the Hebrides, Athalie and Ruy Blas overtures and the Italian Symphony. He seems to embed his German roots in the first movement, which weighs in at nine minutes without the repeat – not quite Brucknerian, but far more bulky and pensive than any other I've heard. Although he accelerates the end as if to prepare for a transition to a more conventional outlook, it's just a tease, as the rest cannot escape being colored by the accumulated weight of the opening – its overcast pervades the Andante, the minuet only hints at a slight awakening and the finale cannot fully rouse – overall, a fascinating and unique, if highly eccentric, interpretation.

- George Szell, Cleveland Orchestra (1947, Columbia LP, 24:10 + F + T = 27:20) (1962, Epic LP, Sony CD, 27:00 + T = 27:25)

Cut mostly during his second recording sessions after assuming the leadership of the Cleveland Orchestra (the first sessions produced a fine Mozart Symphony # 39, Beethoven Fourth and five Dvorak Slavonic Dances), but completed and released four years later, the Szell/Cleveland Italian was an ideal vehicle to display their trademark precision, tight ensemble and sensitive balances. The orchestra was already quite accomplished under Leinsdorf and Rodzinski, its prior conductors – although pushed to the limit, it managed to keep pace in a frantic 27-minute 1946 Rodzinski-led Schumann First. Szell would hone it to an even finer standard of execution, but here the refined performance proudly asserts itself as if to celebrate the glorious heights the orchestra had already obtained in the first year of Szell's tenure. Remarkably, they repeated the feat nearly verbatim in their 1962 stereo remake having nearly identical timings and the same subtle inflections. Both take the repeat in the minuet, but not the trio.

- Mario Rossi, Turin Symphony Orchestra (1947, Decca 78s, 27:00 + F = 30:00)

The timings alone evidence Rossi's position at the mid-point between the leisurely unfolding of Unger and the fleet keenness of Szell. Indeed, this is a middle-of-the-road rendition devoid of much characterization or enthusiasm. Known mostly as a conductor of Italian opera, Rossi and his Italian orchestra suggest no particular identification with the work's nominal subject nor the composer's impetus, but rather provide a pleasant, moderate, unexceptional and rather dutiful half-hour. Interestingly, in light of Decca releasing two versions in such short succession, the December 1948 Gramophone review by "L. S." expressed incredulity that Decca had withdrawn the Unger set in favor of this one and speculated that "perhaps the idea was that it would be interesting to have an Italian orchestra playing a work which owed all its inspiration to Italy."

While citing the new version's comparative vitality and spirit (which, in turn, paled in comparison to Harty and Koussevitzky – how readily some reviewers forget, or perhaps never knew), he felt that the Andante was so slow (actually 6:36 vs. Unger's 6:09) that it "seems to have depressed the orchestra so much that it plays the third movement without much conviction, and the trio is dreary in the extreme." In a September 1950 Gramophone review of the long-play transfer, "R. H." piled on, dubbing it "a poor performance and therefore I cannot understand why Decca has bothered to issue it on LP."

While citing the new version's comparative vitality and spirit (which, in turn, paled in comparison to Harty and Koussevitzky – how readily some reviewers forget, or perhaps never knew), he felt that the Andante was so slow (actually 6:36 vs. Unger's 6:09) that it "seems to have depressed the orchestra so much that it plays the third movement without much conviction, and the trio is dreary in the extreme." In a September 1950 Gramophone review of the long-play transfer, "R. H." piled on, dubbing it "a poor performance and therefore I cannot understand why Decca has bothered to issue it on LP."

- John Barbirolli, Hallé Orchestra (1948, HMV 78s, 25:00 + F = 28:00)

To close out the 'forties recordings, Barbirolli and his revitalized Hallé Orchestra show off their restored eminence with particularly fine articulation that gives the finale an extra rhythmic bounce and with uncommonly poised balances that boost the winds to a level of rare prominence for the era. (But for the inaudible timpani, it would sound fully modern.) The relaxed and fluid grace of the lyric segments is particularly notable compared to the fleet (perhaps to squeeze it onto two sides) and athletic Barbirolli/Hallé Hebrides Overture recorded two months later, a testament to Barbirolli's experience as an accompanist, prepared to adapt to each situation rather than impose a uniform approach across the board. Although never feeling rushed, the entire Italian was fit onto six full sides by splitting the third and fourth movements. Remarkably, though, there is barely a second's gap between the second and third, and the third and fourth, movements, which literally flow together on the fourth and fifth sides, thus emphasizing a sense of overall continuity.

![]() The 1950s, and especially the advent of the LP, unleashed an outpouring of Italians – the monaural half of the decade alone saw a dozen studio versions by Reiger/Munich (DG, 1950), Cantelli/Philharmonia (HMV, 1951), Kubelik/Philharmonia (HMV, 1951), Pedrotti/Czech (Supraphon, 1951), Dorati/Minneapolis (Mercury, 1952), Krips/London Symphony (Decca, 1953), Leinsdorf/Rochester (Columbia, 1954), Swarowski/Vienna Symphony (Music Treasures, 1954), Beinum/Concertgebouw (Philips, 1955), Boult/London Philharmonic (Westminster, 1955), Klemperer/Vienna Symphony (Vox) and Markevitch/Radio France (Columbia, 1955). From the LP era and beyond, I've especially enjoyed these:

The 1950s, and especially the advent of the LP, unleashed an outpouring of Italians – the monaural half of the decade alone saw a dozen studio versions by Reiger/Munich (DG, 1950), Cantelli/Philharmonia (HMV, 1951), Kubelik/Philharmonia (HMV, 1951), Pedrotti/Czech (Supraphon, 1951), Dorati/Minneapolis (Mercury, 1952), Krips/London Symphony (Decca, 1953), Leinsdorf/Rochester (Columbia, 1954), Swarowski/Vienna Symphony (Music Treasures, 1954), Beinum/Concertgebouw (Philips, 1955), Boult/London Philharmonic (Westminster, 1955), Klemperer/Vienna Symphony (Vox) and Markevitch/Radio France (Columbia, 1955). From the LP era and beyond, I've especially enjoyed these:

- Arturo Toscanini, NBC Symphony Orchestra (1954, RCA LP, BMG CD, 25:43 + F = 28:35)

Although officially released, this was not a studio recording per se but rather an amalgam of the fourth-to-last concert of Toscanini's extraordinary career and its rehearsals.

(Interestingly, the broadcast, released intact on a Melodram CD, is slightly more yielding, but for the the LP he opted to substitute the more reserved allegro and considerably faster minuet from the rehearsal.) While his looming retirement must have weighed heavily, rather than fall back upon the rigid determination that scarred many of his late recordings Toscanini produced a splendid, spirited Italian, perhaps as a final salute to his own roots (and he would begin his penultimate concert with his compatriot Rossini's Semiramide Overture). While often disappointing elsewhere, his late, simplified style seems fully appropriate to the work's economical modesty. Even so, he spices the first movement with crisp brass and timpani accents and propels it with a degree of subtle tempo flexibility that is not only unusual toward the end of his career but wholly absent from his two extant earlier concert presentations in his first (1938) and fifth (1942) NBC concert seasons. Only his 1938 concert includes the first movement repeat. Another anomaly – rather than quicken the pace as in most of his later recordings, the inner movements here are considerably more relaxed than in his earlier concerts. And as if to rebut the persistent fiction that Toscanini followed scores literally – a myth that, admittedly, he helped foster – Mortimer Frank points out that in all his Italian performances Toscanini reinforces the distinctive saltarello rhythm by replacing the timpani trills [beginning 20 measures after rehearsal "D"] with triplet figures. The only blemish is some blurring of the rapid string runs, which also slip out of synch with the winds, a problem common to more than a few Italians before and since. The sound is detailed yet atmospheric, aided by the natural ambiance of Carnegie Hall. In contrast, Guido Cantelli, Toscanini's protégé, already had departed considerably from his mentor's style when he led the Philharmonia in a far smoother, blended and relaxed HMV recording the following year (27:10 + F = 30:15).

(Interestingly, the broadcast, released intact on a Melodram CD, is slightly more yielding, but for the the LP he opted to substitute the more reserved allegro and considerably faster minuet from the rehearsal.) While his looming retirement must have weighed heavily, rather than fall back upon the rigid determination that scarred many of his late recordings Toscanini produced a splendid, spirited Italian, perhaps as a final salute to his own roots (and he would begin his penultimate concert with his compatriot Rossini's Semiramide Overture). While often disappointing elsewhere, his late, simplified style seems fully appropriate to the work's economical modesty. Even so, he spices the first movement with crisp brass and timpani accents and propels it with a degree of subtle tempo flexibility that is not only unusual toward the end of his career but wholly absent from his two extant earlier concert presentations in his first (1938) and fifth (1942) NBC concert seasons. Only his 1938 concert includes the first movement repeat. Another anomaly – rather than quicken the pace as in most of his later recordings, the inner movements here are considerably more relaxed than in his earlier concerts. And as if to rebut the persistent fiction that Toscanini followed scores literally – a myth that, admittedly, he helped foster – Mortimer Frank points out that in all his Italian performances Toscanini reinforces the distinctive saltarello rhythm by replacing the timpani trills [beginning 20 measures after rehearsal "D"] with triplet figures. The only blemish is some blurring of the rapid string runs, which also slip out of synch with the winds, a problem common to more than a few Italians before and since. The sound is detailed yet atmospheric, aided by the natural ambiance of Carnegie Hall. In contrast, Guido Cantelli, Toscanini's protégé, already had departed considerably from his mentor's style when he led the Philharmonia in a far smoother, blended and relaxed HMV recording the following year (27:10 + F = 30:15).

- Leopold Stokowski, National Philharmonic Orchestra (1977, Columbia LP, Cala CD, 29:35)

Stokowski's career is remarkable not only for its sheer longevity but for his sustained focus and energy – no autumnal reflection for him!

He first led the Italian in 1914, once more in 1917, and not again until recording it for the very first time sixty years later – at age 95 – and it's a beauty, without the slightest hint of fatigue or lapse in concentration. Rather, it brims with romantic feeling, a superb blend of not merely recalling but being immersed in youthful affection, yet with a tinge of wisdom that smoothes out the rough edges of actual experience. In rediscovering an old forgotten friend, perhaps the Italian impelled Stokowski to revert to the passions of his own formative years and to identify with the composer. The specially-assembled orchestra plays for him with audible affection.

He first led the Italian in 1914, once more in 1917, and not again until recording it for the very first time sixty years later – at age 95 – and it's a beauty, without the slightest hint of fatigue or lapse in concentration. Rather, it brims with romantic feeling, a superb blend of not merely recalling but being immersed in youthful affection, yet with a tinge of wisdom that smoothes out the rough edges of actual experience. In rediscovering an old forgotten friend, perhaps the Italian impelled Stokowski to revert to the passions of his own formative years and to identify with the composer. The specially-assembled orchestra plays for him with audible affection.

- Pablo Casals, Marlboro Festival Orchestra (1963, Columbia LP, Sony CD, 29:00)

Casals was a mere 86 but he, too, embraced new challenges, closing his sweeping career by guiding the orchestra at the annual Marlboro music festivals which selflessly melded the wisdom, enthusiasm and devotion of present and future superstars. Their Italian manages to fully capture the personality of the composer – gentle but not precious, finely detailed but not self-conscious, energetic without a macho edge, vivid without aggression. The nimble ensemble of 45 players crafts chamber cohesion and balances, every phrase shaped and voiced with utmost precision yet vibrant with Casals's paramount humanity and fully steeped in the setting of natural splendor. The Andante is patient and hypnotic, the finale enchanting with delicate filigrees, their spare textures anticipating the trend of historically-informed performances yet to emerge.

- Giuseppe Sinopoli, Philharmonia (1984, DG, 32:00)

Trained as a surgeon and psychiatrist, Sinopoli saw in all music the existential and spiritual problems of life. A free-thinker, his work was highly individual, analytic and eccentric, as likely to impress as revelatory as to deter as bizarre.

His Italian originally was coupled with a stunning half-hour Schubert Unfinished – massive, seething, haunting and profound, on the threshold of Bruckner – and accompanied by a bafflingly dense essay in which Sinopoli explored "Dream and Memory, whose heavily veiled speech is always undermined by the tenuous, ephemeral nature of what supports their emergence on the one hand, and the sudden howl and agonized shivering provoked by the sensation of emptiness and silence on the other … ." Heavy stuff! The Italian is far more orthodox, if only by comparison, yet full of subtle adjustments and absorbing details in its outer movements, while the inner ones are deep, dark, flowing and probing – overall, a thinking man's (or woman's, of course) journey reflecting the composer's own searching intellect.

His Italian originally was coupled with a stunning half-hour Schubert Unfinished – massive, seething, haunting and profound, on the threshold of Bruckner – and accompanied by a bafflingly dense essay in which Sinopoli explored "Dream and Memory, whose heavily veiled speech is always undermined by the tenuous, ephemeral nature of what supports their emergence on the one hand, and the sudden howl and agonized shivering provoked by the sensation of emptiness and silence on the other … ." Heavy stuff! The Italian is far more orthodox, if only by comparison, yet full of subtle adjustments and absorbing details in its outer movements, while the inner ones are deep, dark, flowing and probing – overall, a thinking man's (or woman's, of course) journey reflecting the composer's own searching intellect.

- Pierre Monteux, San Francisco Symphony (1947, Music and Arts CD, 25:45)

Taken from a weekly series of hour-long broadcast concerts, here's an antidote to challenge the notion that "faster is better" so as to ostensibly reflect the unbridled enthusiasm reflected in the composer's correspondence. The sponsor strongly disfavored works exceeding 20 minutes, and Monteux generally complied by programming light classics, overtures and occasional isolated movements of symphonies and concertos (and even went so far as to play only halves of the tightly-integrated Beethoven Fifth!). Yet he somehow managed to fit the entire Italian into a single program, and brought it in at well under 26 minutes – not only intact but including all repeats! He pushes the allegro well beyond vivace into a furiously manic moto perpetuo that, at 8:45, seems more relentlessly frantic than excited – even sprinters need to slow down for a distance run – and thoroughly out of character with Monteux's genial temperament. Was the torrid pace out of pique for the sponsor's constraint or reflective of Monteux's genuine view of the opening? We'll never know, as this appears to be his only recorded performance of the Italian. In any event, having gotten the frenzied opening out of his system, the rest is on the fast side of brisk but not uncomfortably so, with the minuet and trio suggesting rugged urgency and the crisply-played finale a sly tease, beginning moderately but accelerating to a thrilling close.

- Leonard Bernstein, New York Philharmonic (1958, Columbia LP, Sony CD, 29:40)

Seemingly an ideal choice to imbue the Italian with youthful discovery, Bernstein does not disappoint, at least at the outset. Typical of his recordings at the outset of his tenure as Music Director of the New York Philharmonic,

he radiates energy and zeal by plunging headlong into the opening theme, leaning into each repetition and leaping into the coda. But as if to thwart expectations (and perhaps to suggest underlying maturity), his measured and thickly-textured Andante that follows seems a bit out of place. Yet the overall mood recovers with some surges of light in a nicely-shaped minuet and a powerful trio that suggests rugged momentum. The finale, too, is curiously slow, pressing forward through a reverberant sonority, boldly sacrificing grace for muscle. Unusual for the time, all the repeats are taken. Bernstein's concert remake with the Israel Philharmonic (1979, DG LP and CD, 30:15) is hobbled by a texturally bland allegro vivace that sets a flavorless mood for the rest, which lacks the focus and drive of the earlier set.

he radiates energy and zeal by plunging headlong into the opening theme, leaning into each repetition and leaping into the coda. But as if to thwart expectations (and perhaps to suggest underlying maturity), his measured and thickly-textured Andante that follows seems a bit out of place. Yet the overall mood recovers with some surges of light in a nicely-shaped minuet and a powerful trio that suggests rugged momentum. The finale, too, is curiously slow, pressing forward through a reverberant sonority, boldly sacrificing grace for muscle. Unusual for the time, all the repeats are taken. Bernstein's concert remake with the Israel Philharmonic (1979, DG LP and CD, 30:15) is hobbled by a texturally bland allegro vivace that sets a flavorless mood for the rest, which lacks the focus and drive of the earlier set.

- Otto Klemperer, Philharmonia Orchestra (1960, EMI LP and CD, 27:10 + F = 30:20)

The primary interest in Klemperer's Italian is his array of the second violins to the right of the podium (rather than the routine 20th century practice, heard in all but some of the most recent recordings, of clustering them behind or aside the first violins on the left). With antiphonal placement, the stereo spread reveals Mendelssohn's fascinating interplay between the two violin choirs that is all too often obscured but here appreciably enlivens the scoring of the outer movements and especially the finale. Interestingly, as traced by Jack Smith, this seemingly novel positioning was not an innovation but rather a reversion to the seating arrangements of the 19th century, which Mendelssohn presumably used with his Gewandhaus orchestra and undoubtedly had in mind when conceiving the Italian, and which modern orchestras increasingly are adopting.

- Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic (1973, DG, 28:10)

I'm not a huge fan of Karajan's approach to most music – to me,

his technical precision can be thrilling, but his aloof objectivity drains music of its essential humanity. Here, though, it works brilliantly, investing the Italian with transcendent care, elegance and lightness that seem an ideal match in sound to the composer's temperament. As Schonberg notes, as a Jew in strongly anti-Semitic Berlin (where his conversion barely mattered) Mendelssohn was taught from childhood to be correct, avoid offense, observe good form, strive for acceptance and proceed with caution. Karajan's Italian – and his 1970 Scottish Symphony and Hebrides Overture – do just that. Playing on tip-toes, his players sublimate their power into painstakingly refined reserves of suppressed emotion that barely simmer under their exquisitely delicate surfaces, perhaps reminding us that after all is said and done the highest calling of art is to suggest emotion rather than display it.

his technical precision can be thrilling, but his aloof objectivity drains music of its essential humanity. Here, though, it works brilliantly, investing the Italian with transcendent care, elegance and lightness that seem an ideal match in sound to the composer's temperament. As Schonberg notes, as a Jew in strongly anti-Semitic Berlin (where his conversion barely mattered) Mendelssohn was taught from childhood to be correct, avoid offense, observe good form, strive for acceptance and proceed with caution. Karajan's Italian – and his 1970 Scottish Symphony and Hebrides Overture – do just that. Playing on tip-toes, his players sublimate their power into painstakingly refined reserves of suppressed emotion that barely simmer under their exquisitely delicate surfaces, perhaps reminding us that after all is said and done the highest calling of art is to suggest emotion rather than display it.

- Peter Maag – Bern Symphony Orchestra (1986, MCA Classics CD, 30:45); Madrid Symphony Orchestra (1998, Arts CD, 29:40)

The Swiss conductor Peter Maag (1919 – 2001) trained under both Furtwangler and Ansermet, and it’s hard to imagine a more disparate set of influences. Mostly known as an opera and Mozart specialist, his most acclaimed recording was a remarkably rich and flowing 1960 Decca/London LP of the Scottish Symphony and Hebrides Overture with the London Symphony Orchestra that still is often cited as the finest of all Mendelssohn orchestral recordings, in which he managed to blend his mentors’ styles into a compelling middle course of tempered impulse. Later in life, he complemented that achievement with two remarkably fine Italians. Although of far slighter stature than the London orchestra, the Bern ensemble projects an extraordinary balance of classical control and surging energy, a fully apt portrait of the composer’s era and personality, poised amid conservative caution and exploratory freedom. The andante is especially effective, propelled by an exquisite layering of textures. The later Madrid version, part of an integral set of the numbered Mendelssohn symphonies, is essentially similar, but with somewhat quicker outer movements and a bit less polish and cohesion, yet with gracious, pointed phrasing in the minuet and a peppier, more forceful finale. Both are fine tributes to a modest but superb Mendelssohn interpreter.

Just "for the record" (so to speak), I've enjoyed and can recommend several more Italians. All are idiomatic, well-played and in good sound but, to me, lack the historical value, stylistic interest and special touches of the ones highlighted above: Munch/Boston Symphony (RCA, 1958), Solti/Israel Philharmonic (Decca, 1958 – especially swift outer movements), Skrowaczewski/Minneapolis (1961, Mercury – ditto), Maazel/Berlin Philharmonic (1960, DG), Abbado/London Symphony (1968, Decca, or 1984, DG – with a much faster Andante), Leppard/English Chamber Orchestra (1977, Erato), Haitink/London Philharmonic (1979, Philips), Levine/Berlin Philharmonic (1989, DG) and Svetlanov/USSR State Orchestra (1982, Melodyia – very slow minuet and trio, but otherwise surprisingly vigorous, considering the source). I'm sure there are others (and I'm sorry if I missed your favorite), but I have my limits …

- Roy Goodman, The Hanover Band (1988, Nimbus CD, 29:00)

- Charles Mackerras, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (1988, Virgin, 28:00)

- Roger Norrington, The London Classical Players (1989, EMI CD, 27:00)

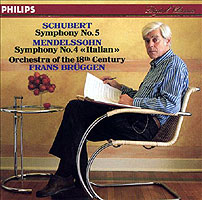

- Frans Bruggen, Orchestra of the 18th Century (1991, Philips, 28:45)

I've clustered these together

|

- Nicholas McGegan, Capella Savaria (2012, Centaur CD, 30:35)

This one merits separate mention – presented not only dynamically and on original instruments but in Mendelssohn's revised versions, the features of which we've already noted. Equally fascinating is its CD companion – the original version of Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto as he had completed the score prior to emendations requested by Ferdinand David, the dedicatee, concertmaster of the Gewandhaus and soloist at the premiere, in which revised form it was published, became known, and is always performed nowadays. As played by Zsolt Kalló, the most noticeable distinction is a vastly different and less scintillating first movement solo cadenza. Most of the other changes seem fairly subtle, including occasional shifts in some of the solo figurations that are mostly simplified. As with the Italian, it's hard to objectively evaluate the two versions of both works, as the published ones have become so familiar, but together they provide an intriguing glimpse into the vagaries of the creative process – and suggest an anomaly in that Mendelssohn's initial impulse might have been superior in the symphony, but not in the Concerto – and definitely not in his Octet. (An earlier and equally fine recording of the original Violin Concerto, with Daniel Hope and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe conducted by Thomas Hengelbrock, had been issued by DG in 2008.)

![]() Beyond all else, the Italian Symphony serves to remind us of the astounding distance – not just temporal or technological but cognitive – between Mendelssohn's time and ours. The world already has vastly shrunk through instant communication, easy travel and shared cultures. In the foreseeable future digital ubiquity will further expand our exposure to the world's knowledge, and virtual-reality gear promises to blur if not eliminate the gulf between perception and actual experience. Yet, kindled only by drawings, books and others' tales, Mendelssohn set out to discover a new world and managed to record in music his immersion in its wonders. Nowadays it seems hard to fathom the challenge and thrill of such a venture into the unknown and the awesome psychic power of its impact.

Beyond all else, the Italian Symphony serves to remind us of the astounding distance – not just temporal or technological but cognitive – between Mendelssohn's time and ours. The world already has vastly shrunk through instant communication, easy travel and shared cultures. In the foreseeable future digital ubiquity will further expand our exposure to the world's knowledge, and virtual-reality gear promises to blur if not eliminate the gulf between perception and actual experience. Yet, kindled only by drawings, books and others' tales, Mendelssohn set out to discover a new world and managed to record in music his immersion in its wonders. Nowadays it seems hard to fathom the challenge and thrill of such a venture into the unknown and the awesome psychic power of its impact.

|

![]() As always, I accept the blame for my musical judgments, but gratefully acknowledge the following sources for the references and quotations, and upon which I have relied for the factual information:

As always, I accept the blame for my musical judgments, but gratefully acknowledge the following sources for the references and quotations, and upon which I have relied for the factual information:

- Alberts, Max: introduction to the Eulenburg miniature orchestral score (Eulenburg, [undated])

- Burr, Charles: notes to the Bernstein/NY Philharmonic LP (Columbia MS 6050, 1959)

- Carse, Adam: History of Orchestration (Kagan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1925)

- Cooper, John Michael: Mendelssohn's Italian Symphony (Oxford, 2003)

- Fish, Rubin D., Jr.: afortmadeofbooks.blogspot.com/2007/07/reading-mendelssohns-4th.html

- Goddard, Scott: notes to the Maag/London Symphony Scottish LP (London CS 6191, 1960)

- Gray, Michael: notes to the Beecham American Columbia Recordings CD set (Sony MH2K 63366, 1977)

- Gray, Thomas: "The Orchestral Music" in Douglass Seaton, ed.: The Mendelssohn Companion (Greenwood Press, 2001)

- Greenfield, Edward: [untitled review of Gardiner recording] (Gramophone)

- Grove, George: "Mendelssohn" article in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Grove, 1905)

- Günter-Klein, Hans: notes to the Gardiner/Vienna CD (DG 289 459 156-2, 1998)

- Günter-Klein, Hans: notes to the Maazel/Berlin LP (DG 138 684, 1961)

- Hall, David: notes to the Steinberg/Pittsburgh LP (Capitol SP 8515, 1959)

- Harrison, Julius: "Felix Mendelssohn" in Robert Simpson, ed.: The Symphony (Penguin, 1968)

- Johnson, Edward: notes to the Stokowski/National Philharmonic CD (Cala CACD 0531, 2001)

- Kennedy, Michael: The Hallé, 1858 - 1983 – A History of the Orchestra (Manchester University Press, 1982)

- Kramer, Jonathan: Listen to the Music (Schirmer, 1988)

- Lyons, James: notes to the Toscanini/NBC LP (RCA Victor LM-1861, 1955)

- "P. M. Y.": "Mendelssohn" article in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Grove, 1954)

- Roney, Marianne: notes to the Klemperer/Vienna LP (Vox PL 11.880, 1961)

- Roy, Klaus G.: notes to the Szell/Cleveland LP (Epic BC 1259, 1963)

- Schonberg, Harold: The Great Conductors (Simon & Schuster, 1967)

- Schonberg, Harold: Lives of the Great Composers, 3d edition (Norton, 1997)

- Seaton, Douglas: "Symphonies and Overtures" in Peter Mercer-Tayor, ed.: Cambridge Companion to Mendelssohn (Cambridge, 2004)

- Smith, Jack D.: Orchestral Seating in Modern Performance – Origins and Variations (MMus thesis, University of Glamorgan at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, 2009)

- Stevens, Denis: notes to the Bernstein/New York Philharmonic CD (Sony SMK47592, 1993)

- Tessler-Mabé, Herman: A Jewish Conductor, a Devoted Mahlerite and a Delicate String: The Musical Life of Heinz Unger, 1985-1965 (Thesis, University of Ottowa, 2010)

- Todd, R. Larry: "Mendelssohn" article in New Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Grove, 2001)

- Todd, R. Larry: notes to the Gardiner/Vienna CD (DG 289 459 156-2, 1998)

- Tovey, Donald Francis: Essays in Musical Analysis (Oxford, 1935)

![]()

Copyright 2016 by Peter Gutmann

copyright © 1998-2016 by Peter Gutmann. All rights reserved.