|

Identical twins often struggle to establish their own personalities. But the indignity of mistaken identity seems even less fair for mere siblings, much less those wholly unrelated, who just happen to look somewhat alike.

The string quartets of Claude Debussy (1862–1918) and Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)  seemed destined to face an identity crisis from the very outset. Reacting to the premiere of the Ravel, critic Pierre Lalo (son of composer Edouard) was hardly alone in proclaiming: "In all the elements it contains and all the sensations it evokes it offers an incredible resemblance to the music of M. Debussy." The bond was cemented in the LP era when they were paired as seemingly inseparable soul-mates, each filling one side of an album. True, the two quartets are distant relatives and do share some superficial traits – they have roughly similar structures; each was an early work that helped introduce its creator's style and establish his fame; and each was the only quartet of its composer, who often are lumped together as the foremost musical Impressionists. And yet, they reflect the distinctive musical personalities of their authors, whose outlooks and significance were quite different despite their comparable prominence and popularity.

seemed destined to face an identity crisis from the very outset. Reacting to the premiere of the Ravel, critic Pierre Lalo (son of composer Edouard) was hardly alone in proclaiming: "In all the elements it contains and all the sensations it evokes it offers an incredible resemblance to the music of M. Debussy." The bond was cemented in the LP era when they were paired as seemingly inseparable soul-mates, each filling one side of an album. True, the two quartets are distant relatives and do share some superficial traits – they have roughly similar structures; each was an early work that helped introduce its creator's style and establish his fame; and each was the only quartet of its composer, who often are lumped together as the foremost musical Impressionists. And yet, they reflect the distinctive musical personalities of their authors, whose outlooks and significance were quite different despite their comparable prominence and popularity.

Like most of his generation, Debussy at first fell under the seemingly irresistible spell of Wagner, whose searching harmonies, massive architecture and sense of unabashed drama represented an alluring revolt against academic strictures and promised to reorient the entire course of Western music. Yet Debussy soon rebelled against the rebellion. In a letter to his friend and fellow composer Ernest Chausson, Debussy wrote of Wagner: "We have been taken in. The richness of the frame causes us to overlook the poverty of ideas." He described his ideal approach as: "to discover the perfect design for an idea and to add only what is absolutely necessary as ornament." Debussy would launch a frontal attack on Wagner's home turf in 1903 with his only opera, Pelléas et Mélisande, whose prosaic text, repressed emotion, modal tonality, delicate orchestration, shreds of occasional melody, absence of arias and steadfast narrative diametrically opposed the opulent, unrestrained German (and Italian) prevailing operatic esthetic.

Like most of his generation, Debussy at first fell under the seemingly irresistible spell of Wagner, whose searching harmonies, massive architecture and sense of unabashed drama represented an alluring revolt against academic strictures and promised to reorient the entire course of Western music. Yet Debussy soon rebelled against the rebellion. In a letter to his friend and fellow composer Ernest Chausson, Debussy wrote of Wagner: "We have been taken in. The richness of the frame causes us to overlook the poverty of ideas." He described his ideal approach as: "to discover the perfect design for an idea and to add only what is absolutely necessary as ornament." Debussy would launch a frontal attack on Wagner's home turf in 1903 with his only opera, Pelléas et Mélisande, whose prosaic text, repressed emotion, modal tonality, delicate orchestration, shreds of occasional melody, absence of arias and steadfast narrative diametrically opposed the opulent, unrestrained German (and Italian) prevailing operatic esthetic.  But as he began the decade of gestation required to craft Pelléas, Debussy launched his revolution with the Prélude á l'après-midi d'un faune and his Quartet.

But as he began the decade of gestation required to craft Pelléas, Debussy launched his revolution with the Prélude á l'après-midi d'un faune and his Quartet.

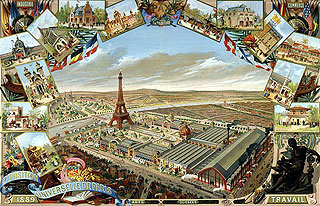

The trigger for Debussy's revolt was the 1889 Paris Universal Exhibition, best remembered nowadays for its landmark – the Eiffel Tower. For Debussy Léon Vallas called it a voyage of artistic discovery through the various countries of the world without ever having to leave Paris:

[He] would listen with the closest attention to the improvisations of popular musicians whose talent had not been stifled by strict scholastic rules and who knew no principle but that of absolute liberty. … Here he found a supple diversity of forms, rhythms, chords and scales, in marked contrast to the stereotyped forms and harmonies, the stiff, symmetrical rhythms and the modal restrictions which he had been taught in vain at the Conservatoire … and he contrasted the grandiloquent art of Bayreuth [i.e., Wagner] with the more direct expressive action of the Oriental theatre.Exposed to a wide variety of non-Western music, Debussy was especially drawn to Indonesian gamelan, a large ensemble of tuned gongs and metallophones,

A gamelan orchestra |

Debussy's outlook hardly arose in isolation but was intimately bound to the broader esthetic shifts of his era. Chief among these was Impressionism. While Debussy shunned the label, Impressionism does seem a valid shorthand for his perspective. Indeed many scholars relate Debussy's music to the progressive visual art movement of his time. Paul Henry Lang cites the Impressionist rejection of architectural boundaries, logical ties and continuity in favor of different colors (in music, sonorities) unified by character and mood, with a de-emphasis of the subject itself (in music, melody). He further compares the Impressionist painters' pointillism (small dots of pure color that merge into a vibrant image only when viewed from a distance) to Debussy's chords of far-removed intervals that excite the senses and produce their desired effect only when heard together. Roy Howat further analogizes Debussy's technique to Monet's illumination of a fixed object from different angles and lighting. Percy Sholes compares his care with texture to the painters' occupation with light. Above all else, for Edward Applebaum the result is a new emphasis on sound for its own sake and the dominance of content over form, sensuality over reasoning, feeling over cognition.

A parallel tectonic change in French culture arose in the literary movement of Symbolism.

Impressionism ...

... and Symbolism (Fernand Khnopff: "I Lock My Door Upon Myself")  |

André Tubeuf adds a parallel political consideration: stung by its loss of the 1870 Prussian war, France was bent on cultural revenge against the German/Austrian hegemony that largely had governed instrumental music for two centuries. Melvin Berger further notes that the War brought to a close the era of positivism (in which reality has an objective existence subject to empirical proof) and paved the way for a philosophy in which objects in the real world exude a fleeting, evanescent atmosphere that the artist depicts through personal response, appealing to the senses rather than the intellect, an approach especially stimulating to Debussy's sensitive ear for sonority and nuance. Consequently, Lang views Debussy's mental world at the turn of the century as particularly attuned to seeking freedom from the era's whipped-up passions, tearful sentimentalism and noisy naturalism (exemplified by Wagner and Richard Strauss).

In conversations with Maurice Emmanuel, Debussy espoused his musical philosophy as including the enrichment of tonality with other scales; free-flowing rhythm unfettered by bar constraints; and floating, incomplete chords for greater nuance. He summed up: "There is no theory. You merely have to listen. Pleasure is the law." Wilfred Mellers calls him a "sensual instinctive atheist" who, when asked by a professor what rule he followed, proudly retorted: "mon plaisir" ("my pleasure") and envisioned his goal as "a form so free as to seem like an improvisation," subordinating rigid form "to a thorough and more extended portrayal of human feelings" so that "music can become more personal, true to life." That aim certainly resonated in Paul Rosenfeld, who in 1920 waxed poetic over the sheer humanity of Debussy's work:

Debussy's music is our own. … It lived in us before it was born. … It made us feel that we had always needed such rhythms, such luminous chords, such limpid phrases, that perhaps we had even heard them sounding faintly in our imaginations. … It seemed fashioned out of certain mysterious experiences that had bubbled, sour and sweet, from out of our lives … and became ours entirely. … [A] fabric of exquisite and poignant moments, his wholes exist entirely in their parts, in their atoms. Each exists for the sake of its own beauty, occupies the universe for an instant then merges and disappears. [This] most liquid and impalpable of musical styles … is forever gliding, gleaming, melting; crystallizing for an instant in some savory phrase, then moving quaveringly onward. It seems to flow through our perceptions.

![]() At the time of the Quartet's premiere on December 29, 1893, Debussy was barely known. (Vallas notes that his first event to attract public attention had been an April 1893 performance of his student cantata La demoiselle élue; the Faune which would secure his fame would be introduced a year later.) Professional judgment was harsh but perhaps predictable. Thus Maurice Kufferath in the Guide musical found it "completely submerged in a flood of deliberate eccentricities, more studied than inspired, more deliberate than deeply felt" and while the Patriote critic conceded certain aspects of its daring originality he complained of its artificiality and lack of balance; another found it bewildering and diabolically difficult. By way of explanation, Vallas belittled the audience of "austere, formal and dogmatic" musicians as "victims of their musical training and slaves of their unconscious habits.

At the time of the Quartet's premiere on December 29, 1893, Debussy was barely known. (Vallas notes that his first event to attract public attention had been an April 1893 performance of his student cantata La demoiselle élue; the Faune which would secure his fame would be introduced a year later.) Professional judgment was harsh but perhaps predictable. Thus Maurice Kufferath in the Guide musical found it "completely submerged in a flood of deliberate eccentricities, more studied than inspired, more deliberate than deeply felt" and while the Patriote critic conceded certain aspects of its daring originality he complained of its artificiality and lack of balance; another found it bewildering and diabolically difficult. By way of explanation, Vallas belittled the audience of "austere, formal and dogmatic" musicians as "victims of their musical training and slaves of their unconscious habits.  They suffer real tortures if an innovator attempts to unwind the myriad bands in which long habits or honest prejudice has swathed them. … It was inevitable that these pure-minded ones should look upon Debussy's composition as a freakish fantasy, quite unsuited to such a high-class form." Ironically, Vallas credits the public as far more amenable to Debussy's spell by virtue of their formal musical ignorance.

They suffer real tortures if an innovator attempts to unwind the myriad bands in which long habits or honest prejudice has swathed them. … It was inevitable that these pure-minded ones should look upon Debussy's composition as a freakish fantasy, quite unsuited to such a high-class form." Ironically, Vallas credits the public as far more amenable to Debussy's spell by virtue of their formal musical ignorance.

Of course, Debussy's defenders were enthralled. Guy Ropartz hailed the Quartet as "a most interesting work" of "poetical themes and rare tone-coloring." Paul Dukas was intrigued by dissonances that "are never harsh but, with their complex interrelationships, create an effect which is indeed almost more harmonious than the consonances" and the melodic "flow as though gliding over a luxurious, artistically-designed and wonderfully-colored carpet." Octave Maus added that it was "so full of happy discoveries, youthful inspiration and exquisite details." Guy Ferchault expanded Vallas's observation by attributing critics' perplexity and hostility to "the originality of its content – the light touch with which it is written, the rhythmic audacities, the modal ambiguity, the floating vagueness of the harmonies, the extremely unusual combinations of the chords and the instrumental colorization."

Despite the general disparagement in his critique, Kufferath allowed that the Quartet perhaps was too novel, eccentric and discomforting for its time and predicted its historical import:  "Our grandchildren will be in a position to judge and perhaps they will call us old fogies for not understanding Debussy, just as we did in the case of our predecessors." Edward Lockspeiser suggests that César Franck's scorn of a prior Debussy work as "musique sur les pointes aiguilles" (literally, music on needle-tips; figuratively, nerve-racking), while intended as censure, is an apt characterization of the Quartet's compelling appeal that requires heightened sensitivity to grasp. Thus Donald Jay Grout contends that to fully appreciate the Quartet, one must submit to its special charm, nuance and exquisite detail and be willing to distinguish calmness from dullness, wit from jollity, gravity from portentiousness, lucidity from emptiness. Nowadays, of course, with the benefit of a century of hindsight and further evolution, we are far better equipped to appreciate Debussy than from the vista of his time.

"Our grandchildren will be in a position to judge and perhaps they will call us old fogies for not understanding Debussy, just as we did in the case of our predecessors." Edward Lockspeiser suggests that César Franck's scorn of a prior Debussy work as "musique sur les pointes aiguilles" (literally, music on needle-tips; figuratively, nerve-racking), while intended as censure, is an apt characterization of the Quartet's compelling appeal that requires heightened sensitivity to grasp. Thus Donald Jay Grout contends that to fully appreciate the Quartet, one must submit to its special charm, nuance and exquisite detail and be willing to distinguish calmness from dullness, wit from jollity, gravity from portentiousness, lucidity from emptiness. Nowadays, of course, with the benefit of a century of hindsight and further evolution, we are far better equipped to appreciate Debussy than from the vista of his time.

Debussy was less than thrilled with the first performance by the Ysaÿe Quartet and he reportedly told the leader: "You played like a pig." Yet he eventually dedicated the work to them, presumably in belated appreciation of their courage in having performed it at all in an otherwise conservative program.

![]() When published the following year, Debussy entitled it "Premier Quatuor en sol mineur, Op. 10" (First Quartet in g minor, Opus 10), which seems triply curious.

When published the following year, Debussy entitled it "Premier Quatuor en sol mineur, Op. 10" (First Quartet in g minor, Opus 10), which seems triply curious.

- Strictly speaking, this was Debussy's first quartet. Yet he never wrote a second, even though in response to Chausson's harsh critique he promised to write another "entirely for you and I shall try to clothe it in more dignified forms." Indeed the Quartet was nearly his sole chamber piece, preceded only by an unpublished juvenile trio and succeeded by three of six projected sonatas he was able to complete at the end of his life. (Tubeuf suggests that, having accomplished all he had set out to do in his "first" quartet, Debussy simply had no need for a second.)

- The key designation seems rather arbitrary – while the Quartet does begin in G minor (and ends in G major) it rambles through distant keys and modes and effectively disclaims a stable tonal base.

- And not only was this his only composition labelled with a specific key but also his only work assigned an opus number – and why # 10? We can only wonder which nine, of his earlier output, he might have deemed worthy of such recognition.

Perhaps the formal title was a fling at respectability, and in retrospect several commentators consider Debussy to have been not a subversive flaming radical but rather a bridge between the comfort of tradition and the challenge of innovation. Indeed the Quartet is hardly free-form, guided solely by whim and instinct, as Debussy's own "pleasure" credo might suggest. Rather its embrace of the past is reflected in its entire structure. Thus Vallas analyzes the first movement as basically in sonata form, with a two-themed exposition, development, recapitulation and coda, while the second and third alternate two principal subjects and thus are modelled on song (with the pizzicato-infused second even evoking a Spanish serenade), and the finale, if the most novel in form, applies established techniques to repetitions of the rhythms of the first movement and reminiscences of the third in building toward the final climax. Berger further notes that the Quartet reverts far earlier than the conventions of Debussy's time, as it is replete with the modes and parallel fourths and fifths of early ecclesiastical music, and embraces the clarity, precision and refinement of 18th century French music. As Sholes observes, the old forms are still present but pushed into the background.

and in retrospect several commentators consider Debussy to have been not a subversive flaming radical but rather a bridge between the comfort of tradition and the challenge of innovation. Indeed the Quartet is hardly free-form, guided solely by whim and instinct, as Debussy's own "pleasure" credo might suggest. Rather its embrace of the past is reflected in its entire structure. Thus Vallas analyzes the first movement as basically in sonata form, with a two-themed exposition, development, recapitulation and coda, while the second and third alternate two principal subjects and thus are modelled on song (with the pizzicato-infused second even evoking a Spanish serenade), and the finale, if the most novel in form, applies established techniques to repetitions of the rhythms of the first movement and reminiscences of the third in building toward the final climax. Berger further notes that the Quartet reverts far earlier than the conventions of Debussy's time, as it is replete with the modes and parallel fourths and fifths of early ecclesiastical music, and embraces the clarity, precision and refinement of 18th century French music. As Sholes observes, the old forms are still present but pushed into the background.

The Debussy Quartet is often referred to as having a cyclical structure, but in that context the term is somewhat misleading. The conventional meaning of the phrase is the use of a motif or entire theme throughout multiple movements as a unifying device.

|

CYCLICAL STRUCTURE: Debussy's opening theme:  rhythmically altered (2d movement):

rhythmically altered (2d movement):

and slowed as a respite in the finale: |

Yet the impact and historical importance of the Quartet lies beyond considerations of formal structure. Rather, numerous commentators point to aspects of its sheer sound. Thus for Grout the Quartet exemplifies the French perspective of music conceived as a sonorous form, shunning the romantic conception of expression that "delivers [a] message about the state of the cosmos or the composer's soul." To Berger Debussy eschewed the well-marked structural organization that characterized music of the past in order to follow the inner logic and direction of ever-shifting harmonies, brief snatches of melody and a kaleidoscope of tone colors. James Keller asserts that Debussy's harmonies inspire momentary excitement rather than underscoring a long-range trajectory. Scholes cites a departure from the diatonic (Beethoven) and chromatic (Strauss, Wagner) systems in favor of reliance on whole-tone scales and parallel motion that contributes to feelings of misty vagueness.  Comparable rhythmic daring arises in passages in which the beat becomes obscure (a 15/8 passage in the third movement) or seems to disappear altogether (the quiescent introduction to the finale). Textural innovation includes the delightful interplay of plucked and bowed strings in the second movement. Applebaum credits Debussy with transcending development, evolutionary feeling and accumulated energy for a mosaic quality of examining granular cells from many viewpoints. For Howat, repetitions are enlivened by strategically-shifted bass and the overall mood of contemplation is abetted by the softening or outright avoidance of cadences. Wallace Brockway and Herbert Weinstock salute Debussy for using the quartet – the most rule-bound of musical media – as the first vehicle for his manifesto that music is to be enjoyed for itself and for the sensations it evokes.

Comparable rhythmic daring arises in passages in which the beat becomes obscure (a 15/8 passage in the third movement) or seems to disappear altogether (the quiescent introduction to the finale). Textural innovation includes the delightful interplay of plucked and bowed strings in the second movement. Applebaum credits Debussy with transcending development, evolutionary feeling and accumulated energy for a mosaic quality of examining granular cells from many viewpoints. For Howat, repetitions are enlivened by strategically-shifted bass and the overall mood of contemplation is abetted by the softening or outright avoidance of cadences. Wallace Brockway and Herbert Weinstock salute Debussy for using the quartet – the most rule-bound of musical media – as the first vehicle for his manifesto that music is to be enjoyed for itself and for the sensations it evokes.

In a deeper way, by eliding traditional structural markers Debussy advanced the process of removing music from the realm of a passive experience, requiring instead that we actively apply ourselves in order to find our own paths to personal meaning. In that sense, he opened a door that ultimately led beyond most of the music we cherish to the serial, microtonal, electronic, minimalist and aleatory work that serious composers would develop through the next century (even though, for most tastes, such approaches go too far beyond our experience and expectations for comprehension, much less enjoyment). It seems quite ironic that freeing music from the restrictions of the past may have been essential to foster its future growth, yet at the same time the result lacked those very qualities that we seek in music as a shared cultural phenomenon, thus depriving it of popular appeal.

![]() A decade later, Ravel's only quartet arose during a turbulent period in his own professional life. Despite the strength of his musical convictions, Debussy's break from the cultural gatekeepers was discrete. Although a top prize-winning student at the Paris Conservatory, he wrote: "I did not want to study what I considered foolishness. Then I realized that I must at least pretend to study in order to get through. So … whenever we were taught anything I made a note in my mind as to whether I considered it right or wrong. Don't imagine for a moment that I told anyone of this. I kept it all to myself." Ravel's experience at the same Conservatoire was quite different and resulted in a scandal that became known as L'affaire Ravel and culminated in the resignation of the Director.

A decade later, Ravel's only quartet arose during a turbulent period in his own professional life. Despite the strength of his musical convictions, Debussy's break from the cultural gatekeepers was discrete. Although a top prize-winning student at the Paris Conservatory, he wrote: "I did not want to study what I considered foolishness. Then I realized that I must at least pretend to study in order to get through. So … whenever we were taught anything I made a note in my mind as to whether I considered it right or wrong. Don't imagine for a moment that I told anyone of this. I kept it all to myself." Ravel's experience at the same Conservatoire was quite different and resulted in a scandal that became known as L'affaire Ravel and culminated in the resignation of the Director.  As traced by Barbara L. Kelly, in 1900 Ravel suffered a double indignity – he was both dismissed from Fauré's composition class for failure to have written an acceptable fugue and eliminated from the prestigious Prix de Rome competition in the preliminary round. The next year he won third place but only by submitting a cantata that clung to (but perhaps parodied) the stilted, timeworn style relished by the judges. He then failed to qualify in 1902 and 1903, and was eliminated in his final attempt in 1905 for the cardinal sins of parallel fifths and a final chord containing a major seventh. Said one judge: "M. Ravel may well take us for windbags but not with impunity will he take us for idiots." The revelation that all the finalists just happened to be students of the jurors prompted a journalist to retort: "Will future prizes be wrested away by intrigue or awarded by idiots?" Observers were further shocked by the snub because Ravel already was an established composer far more famous than any of his rivals – and all but one of his instructors – albeit for works that abraded and even defied the deeply conservative standards of the aptly-named venerable institution. He had already been acclaimed for his 1899 Pavane pour une infante défunte, 1903 Shéhérazade song cycle and especially the 1901 Jeux d'eau, soon to be recognized as the most influential piano piece of its entire era. (His 1903-5 Sonatine and 1904-5 Miroirs would soon follow.) Actually, for the 1903 composition prize Ravel had submitted the first movement of his Quartet and in a way it, too, made quite an impression – the Director expelled him.

As traced by Barbara L. Kelly, in 1900 Ravel suffered a double indignity – he was both dismissed from Fauré's composition class for failure to have written an acceptable fugue and eliminated from the prestigious Prix de Rome competition in the preliminary round. The next year he won third place but only by submitting a cantata that clung to (but perhaps parodied) the stilted, timeworn style relished by the judges. He then failed to qualify in 1902 and 1903, and was eliminated in his final attempt in 1905 for the cardinal sins of parallel fifths and a final chord containing a major seventh. Said one judge: "M. Ravel may well take us for windbags but not with impunity will he take us for idiots." The revelation that all the finalists just happened to be students of the jurors prompted a journalist to retort: "Will future prizes be wrested away by intrigue or awarded by idiots?" Observers were further shocked by the snub because Ravel already was an established composer far more famous than any of his rivals – and all but one of his instructors – albeit for works that abraded and even defied the deeply conservative standards of the aptly-named venerable institution. He had already been acclaimed for his 1899 Pavane pour une infante défunte, 1903 Shéhérazade song cycle and especially the 1901 Jeux d'eau, soon to be recognized as the most influential piano piece of its entire era. (His 1903-5 Sonatine and 1904-5 Miroirs would soon follow.) Actually, for the 1903 composition prize Ravel had submitted the first movement of his Quartet and in a way it, too, made quite an impression – the Director expelled him.

Despite their differing experiences at the Conservatoire, Ravel and Debussy had much in common. Naomi Shibatani cites influence by the Symbolist poets and Impressionist artists; intrigue with Eric Satie's iconoclastic attitude and love of miniatures and simplicity; the Russians' use of modality, unique harmonies and ostinato techniques; and the Far Eastern scales, timbres and rhythms introduced at the 1889 World Exhibition. Yet they had fundamentally different musical personalities, outlooks and goals. Where Debussy freely innovated with loose structure and without inhibition, Ravel sought restraint, perfection and refinement within the bounds of predictable traditional forms and classical elegance. More specifically, Shibatani differentiates their approaches to: themes and melodies (Debussy layers and transforms fragments, while introducing contrasting motivic gestures; Ravel's themes are a dominant feature, distinctly clear and recognizable, restated intact with different accompaniment), modes and tonality (Debussy prefers whole-tone scales with all notes equal and no leading tones; Ravel frequently uses Phrygian and Dorian modes, derived from Andalusian folk music and his Basque heritage), rhythm and pulse (Debussy's fluctuate, with ambiguous bar lines, tied notes, dotted rhythms, off-beats and fluctuating duple and triple time; Ravel's are clear, conforming to the basic pulse), harmonic progression  (Debussy uses gradual harmonic pacing, colorful effects, sonorities that please the ear and chords conveying no harmonic function or hierarchy; Ravel's harmonic direction is clear and solidly rooted in tonality); and textures (Debussy's are wide-ranging, with greater layering of sonorities and rhythmic polyphony; Ravel's voices lie in closer proximity). Overall, Jane Ade Sutarjo considers Ravel's materials to be smoother, more intimate and purer than Debussy's – and, of particular relevance here, closer to the character of string instruments.

(Debussy uses gradual harmonic pacing, colorful effects, sonorities that please the ear and chords conveying no harmonic function or hierarchy; Ravel's harmonic direction is clear and solidly rooted in tonality); and textures (Debussy's are wide-ranging, with greater layering of sonorities and rhythmic polyphony; Ravel's voices lie in closer proximity). Overall, Jane Ade Sutarjo considers Ravel's materials to be smoother, more intimate and purer than Debussy's – and, of particular relevance here, closer to the character of string instruments.

Ravel deeply admired Debussy. He declared that only upon hearing the Prélude á l'après-midi d'un faune did he understand what music was and he prepared a two-piano version of that seminal work. He was a founding member of the Apaches, a group of artistic rebels who attended and boisterously cheered each performance of Pelléas. Debussy reciprocated, offering suggestions during rehearsals for the premiere of Ravel's Quartet. (A persistent myth is that Debussy urged Ravel not to change a thing, but according to more recent scholarship he merely suggested tweaking the balances and applying more volume in anticipation of the absorption of sound by an audience.) Louis Laloy, a biographer of both composers, claimed that Debussy and Ravel had an excellent social and artistic relationship, despite their vastly different personalities and lifestyles. As outlined by Robert Orledge, Debussy was a self-described "happiness addict" – morally irresponsible in his pursuit of pleasure (even driving his first wife to attempt suicide over one of his many affairs), apolitical, opinionated, irritable and largely focused on music. By contrast, Arbie Orenstein describes Ravel as a style-conscious dandy (among the first in France to wear whites and pastels), a socialist, a life-long bachelor with no known romantic attachments, and wide-ranging interests reflected in his library of rare French classic editions of books on gardening, travel, history, interior decorating, animals and personal grooming – but few on music other than folk. Bernard Jacobson asserts that cliques of over-zealous partisans pulled them apart. Laloy blamed the breach on "too many stupid meddlers [who] seemed to take pleasure in making [the break between them] inevitable" by inventing a rivalry, claiming that Ravel's quartet imitated Debussy's or that Debussy's later piano works cribbed Ravel's. Yet "their respect for each other was entirely mutual [and] I can vouch for the fact that they both regretted the rupture." In 1912 Ravel said, rather elliptically: "It's probably better for us, after all, to be on frigid terms for illogical reasons." Even so, in 1922 Ravel dedicated his Sonata for Violin and Cello to Debussy's memory; its extreme technical ventures seem a tribute to the innovations of his mentor.

![]() Despite superficially similar structural plans (sonata-form first movement; playful, pizzicato-flavored second; lyrical, relaxed third; spirited finale) the fundamental differences between the two composers are evident at very outset by comparing their Quartets' opening themes. Debussy's is gruff, with a jagged rhythm, played loudly, with accents and in unison so as to demand attention, insistently repeats itself before lightening the texture and volume and shifting the tonality, and is marked "très décidé" (very resolute). In marked contrast, Ravel's is marked "très douce" (very gentle) and indeed it is exquisitely sweet and lovely, in a four-square rhythm, played softly, introduced by the first violin (as was traditional in quartets) while the other instruments provide active but fully supportive harmony, floating in as though to suggest a welcoming invitation.

Despite superficially similar structural plans (sonata-form first movement; playful, pizzicato-flavored second; lyrical, relaxed third; spirited finale) the fundamental differences between the two composers are evident at very outset by comparing their Quartets' opening themes. Debussy's is gruff, with a jagged rhythm, played loudly, with accents and in unison so as to demand attention, insistently repeats itself before lightening the texture and volume and shifting the tonality, and is marked "très décidé" (very resolute). In marked contrast, Ravel's is marked "très douce" (very gentle) and indeed it is exquisitely sweet and lovely, in a four-square rhythm, played softly, introduced by the first violin (as was traditional in quartets) while the other instruments provide active but fully supportive harmony, floating in as though to suggest a welcoming invitation.

The opening of the Ravel Quartet |

The opening of the DebussyQuartet |

And yet, perhaps the bristling comments were not wholly unwarranted; while the Debussy quartet stays on a relatively even emotional keel, the Ravel descends into more challenging territory as it proceeds.  The first movement is truly gorgeous and the second delightfully playful, but then the third is cast in the chilly key of G-flat and unfolds as more bittersweet and atmospheric than tuneful, and the finale, while energetic, presents even knottier challenges to discern, much less embrace, its structure. In retrospect, Roland-Manuel deemed the Quartet "the most spontaneous work Ravel has ever written" and saluted his balance of "forceful expression within the framework of an uncompromising classicism without breaking it." Harry Holbreich agrees, calling it a "youthful utterance of irresistible charm, showing an open tenderness and heartfelt spontaneity." Ravel himself later characterized his Quartet rather modestly as "artless strength" and placed his critics in a sympathetic and benevolent perspective, asserting that first impressions react to the most superficial elements and peculiarities rather than deeper content: "[O]ften it is not until years after, when the means of expression have finally surrendered all their secrets, that the real inner emotion of the music becomes apparent."

The first movement is truly gorgeous and the second delightfully playful, but then the third is cast in the chilly key of G-flat and unfolds as more bittersweet and atmospheric than tuneful, and the finale, while energetic, presents even knottier challenges to discern, much less embrace, its structure. In retrospect, Roland-Manuel deemed the Quartet "the most spontaneous work Ravel has ever written" and saluted his balance of "forceful expression within the framework of an uncompromising classicism without breaking it." Harry Holbreich agrees, calling it a "youthful utterance of irresistible charm, showing an open tenderness and heartfelt spontaneity." Ravel himself later characterized his Quartet rather modestly as "artless strength" and placed his critics in a sympathetic and benevolent perspective, asserting that first impressions react to the most superficial elements and peculiarities rather than deeper content: "[O]ften it is not until years after, when the means of expression have finally surrendered all their secrets, that the real inner emotion of the music becomes apparent."

Despite its familiar elements, Ravel's outlook was hardly neo-classical in the sense of a full reversion to prior musical grammar. In the second movement trills and tremelos "create a lustrous sheen" (Berger) and "stunning coloration" (Keller) by harmonizing the instruments in novel ways while cross-rhythms and -accents suggest Spanish dance and even "a gigantic guitar" (Simeone). The third movement creates even more novel textures with trills, tremelos and portions played "sur la touche" (on the fingerboards) and creates an "improvisatory, rhapsodic feeling" (Berger) by rapidly shifting among keys and between triple and common meter. Much of the finale is written in quintuple time and thus challenges a feeling of metric regularity – but, rather teasingly, ends with a conventional rousing buildup to a final tonic chord. Ravel clearly used his Quartet as a vehicle to explore a wealth of stylistic possibilities that would come to characterize his mature work. Heard today, it signals a personality poised between asserting rebellion and craving acceptance.

![]() Unfortunately, beyond the score itself we have no reliable evidence of how Debussy meant his quartet to be heard – and only a few secondary clues in his documented pianism. Although he focused on composing rather than performing, those who heard him described his playing as extremely sensitive, caressing rather than striking the keys, "liberating the piano from its hammers" in Harold Schonberg's telling phrase.

Unfortunately, beyond the score itself we have no reliable evidence of how Debussy meant his quartet to be heard – and only a few secondary clues in his documented pianism. Although he focused on composing rather than performing, those who heard him described his playing as extremely sensitive, caressing rather than striking the keys, "liberating the piano from its hammers" in Harold Schonberg's telling phrase.

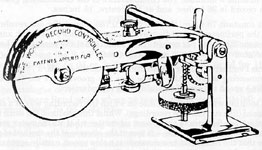

Welte vorsetzer "playing" a piano |

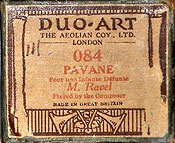

Ravel, too, left traces of his art in the form of five piano rolls cut in a June 1922 session,  but using the cruder and far more common Duo-Art system that directly registered only the notes and their duration without nuance, relying on an engineer to approximate one of 16 levels of loudness. Rather than a wide variety of mood or melodic content, the repertoire comprised three misty, atmospheric pieces – "La vallée des cloches" and "Oiseaux tristes" from Miroirs and "Le gibet" from Gaspard de la nuit – plus the "Toccata" from Le Tombeau de Couperin and the ever-popular Pavane pour une infante défunte. Despite some lumpy chords and bizarre emphases in the Pavane, Ravel's playing is generally understated, with reduced dynamic range and little expression, but that might be more a function of coping with, and perhaps being intimidated by, the mechanics of the Duo-Art device, and a consequence of its inherent limitations, than an authentic representation of his interpretive target, for which we have more direct evidence, as noted below.

but using the cruder and far more common Duo-Art system that directly registered only the notes and their duration without nuance, relying on an engineer to approximate one of 16 levels of loudness. Rather than a wide variety of mood or melodic content, the repertoire comprised three misty, atmospheric pieces – "La vallée des cloches" and "Oiseaux tristes" from Miroirs and "Le gibet" from Gaspard de la nuit – plus the "Toccata" from Le Tombeau de Couperin and the ever-popular Pavane pour une infante défunte. Despite some lumpy chords and bizarre emphases in the Pavane, Ravel's playing is generally understated, with reduced dynamic range and little expression, but that might be more a function of coping with, and perhaps being intimidated by, the mechanics of the Duo-Art device, and a consequence of its inherent limitations, than an authentic representation of his interpretive target, for which we have more direct evidence, as noted below.

Further sonic guidance may be gleaned from a 2012 recording by the Eroica Quartet (Resonus), which sought to emulate performance practices of Debussy's and Ravel's time. The most prominent feature is their use of all gut strings, which were prevalent until the early 1900s and which enable the instruments to richly blend, a departure from the brilliant tone and dominance of the first violin to which we are accustomed, and which raises the inner voices to a position of equality that, in turn, fortifies the harmony.  Minimal vibrato and rather subtle portamento combine with moderate accenting for an overall aura of smooth subtlety that is evident from the outset when the unison opening phrase of the Debussy emerges as a mere statement without its usual assertive edge. Esthetic throwbacks aside, in at least one respect the Eroica's recording is thoroughly modern – as a vanguard of future music marketing, it was released not on physical media but only by download.

Minimal vibrato and rather subtle portamento combine with moderate accenting for an overall aura of smooth subtlety that is evident from the outset when the unison opening phrase of the Debussy emerges as a mere statement without its usual assertive edge. Esthetic throwbacks aside, in at least one respect the Eroica's recording is thoroughly modern – as a vanguard of future music marketing, it was released not on physical media but only by download.

Several scholars have analyzed the evolution of quartet playing in and since Debussy's time.  As summarized by Nancy November, three principal techniques emerged in the 1920s. Vibrato (small, rapid pitch variations by shaking the arm, the wrist or the finger stopping a string) began as an occasional ornament but became a basic element of continuous tone production. She notes that wide, slow vibrato lends a richness and poignancy to slower movements, while more rapid vibrato creates a sense of urgency, destabilization and onward drive in sections of fast tempos or rapid harmonic rhythm. Portamento refers to sliding between adjacent notes rather than articulating them and was used both in upward and downward flows. Rubato is an elasticity of tempo to avoid metronomic regularity (and is both brief and subtle, as distinguished from acceleration, deceleration, dramatic pauses and other prominent overall shifts). November considers all three devices as intended to "win friends" by overcoming a classical music stereotype of stifled emotion and impersonality and to render art as expressive and intimate as possible. Beyond such direct communication with concert audiences, she posits that they were of particular value to overcome the soulless mechanism of early recordings and to suggest a degree of seriousness that the discs didn't convey. Whether or not due to improvements in recording technology or listeners' acceptance of mechanical reproduction, attitudes soon shifted. The 1955 Oxford Companion to Music asserted: "One of the strongest bonds between a musical artist and his audience is the audience's unconscious recognition of the artist's confidence in himself. … A clear, strong melodic line brings into existence an impression of artistic purpose and quiet power, [whereas] a wavering line [creates an impression] of doubt and insecurity." Even so, to varying degrees these techniques characterize all early, and many later, recordings of the Quartets. (While nowadays portamento is extinct and rubato sparce, vibrato persists in much modern string playing – some would say excessively so.)

As summarized by Nancy November, three principal techniques emerged in the 1920s. Vibrato (small, rapid pitch variations by shaking the arm, the wrist or the finger stopping a string) began as an occasional ornament but became a basic element of continuous tone production. She notes that wide, slow vibrato lends a richness and poignancy to slower movements, while more rapid vibrato creates a sense of urgency, destabilization and onward drive in sections of fast tempos or rapid harmonic rhythm. Portamento refers to sliding between adjacent notes rather than articulating them and was used both in upward and downward flows. Rubato is an elasticity of tempo to avoid metronomic regularity (and is both brief and subtle, as distinguished from acceleration, deceleration, dramatic pauses and other prominent overall shifts). November considers all three devices as intended to "win friends" by overcoming a classical music stereotype of stifled emotion and impersonality and to render art as expressive and intimate as possible. Beyond such direct communication with concert audiences, she posits that they were of particular value to overcome the soulless mechanism of early recordings and to suggest a degree of seriousness that the discs didn't convey. Whether or not due to improvements in recording technology or listeners' acceptance of mechanical reproduction, attitudes soon shifted. The 1955 Oxford Companion to Music asserted: "One of the strongest bonds between a musical artist and his audience is the audience's unconscious recognition of the artist's confidence in himself. … A clear, strong melodic line brings into existence an impression of artistic purpose and quiet power, [whereas] a wavering line [creates an impression] of doubt and insecurity." Even so, to varying degrees these techniques characterize all early, and many later, recordings of the Quartets. (While nowadays portamento is extinct and rubato sparce, vibrato persists in much modern string playing – some would say excessively so.)

![]() Only a single recording of the Debussy Quartet appears to have been made during his life,

Only a single recording of the Debussy Quartet appears to have been made during his life,

The London Quartet |

Two more single-sided Andantes followed in 1922. The recording career of the Catterall Quartet, a second British group, was brief but notable – its 1923 Brahms C-minor quartet was acclaimed at the time to have been the very first complete quartet on record (although Frank Forman suggests that the honor should go to a 1922 Busch Quartet set of the spurious "Haydn" Quartet in F, Op. 3 # 5), and it would go on to cut pioneering sets of the first two Beethoven quartets (plus his Op. 130, never issued). Unlike the London's radical surgery, the Catterall's HMV Andante was a skillful abridgement, cutting the introduction and two of the repetitive and transitional sections to present a decent taste of the whole movement, but the slow basic tempo (about 60 vs. the 80 eighth-notes per minute specified in the score), thick textures and liberal use of portamento lend a torpid feeling.

The Catterall Quartet |

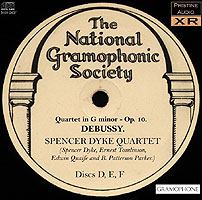

The very late acoustical era produced two complete sets. For part of its very first issue, the National Gramophonic Society awkwardly crammed the Spencer Dyke String Quartet's rendition onto six sides by reversing the order of the inner movements and splitting the third between sides 2 and 3. The Society had been founded by Compson MacKenzie, the publisher of Gramophone magazine, as a subscription service to issue recordings of chamber music in which the established labels had shown little interest. Dyke served on its board, and his quartet recorded 15 major works, most phonographic premieres, for NGS before the label's demise in 1931 (ironically in part because its success may have helped convince its major label competitors of the genre's commercial viability). In 2006 Andrew Rose's Pristine Classical began restoring the NGS series, including the Spencer Dyke Quartet's Debussy Quartet.  Rose justifiably prides himself on sprucing up older recordings with a wealth of sophisticated computer techniques and the degree of near-hi-fi sound he was able to extract in his digital transfer is astounding. Yet collectors' less intrusive transfers of the Dyke Quartet's other acoustical NGS recordings (the contemporaneous Beethoven Op. 74, Brahms Sextet, Op. 18, Schoenberg's Verklärte Nacht) reflect the far more limited fidelity that typified the acoustical process – and more accurately convey what a listener of the time could have expected to hear even with the best available equipment. While it's undeniably thrilling to be able to glean musical information that the original discs never yielded to their intended audience (here including hints of the instruments' woody resonances), perhaps that modern advantage not only falsifies the sound of the time but is unfair, both for comparison with contemporary competition and to the artists, who were required to conform their performances to accommodate the mechanical criteria (e.g., having to compress dynamics and skew balances for the acoustical horn) and at the same time were able to take cover within a safety zone of the technology's inherent limits to conceal some of the inevitable blemishes in their work that radical restoration reveals. But even after mentally tuning out Pristine's sonic enhancements, the Dyke Quartet still comes across as remarkably modern, except for ample portamento – well-balanced and precise, with minimal vibrato or tempo fluctuation. Yet they also seem unduly rushed, mechanical and cold both in the first movement where they largely ignore the score specification of rubato and in the finale where it indicates passion. Even so, the sharp articulation of their playing tends to convey a contagious enthusiasm and the third movement is considerably more expressive, as the score specifies there.

Rose justifiably prides himself on sprucing up older recordings with a wealth of sophisticated computer techniques and the degree of near-hi-fi sound he was able to extract in his digital transfer is astounding. Yet collectors' less intrusive transfers of the Dyke Quartet's other acoustical NGS recordings (the contemporaneous Beethoven Op. 74, Brahms Sextet, Op. 18, Schoenberg's Verklärte Nacht) reflect the far more limited fidelity that typified the acoustical process – and more accurately convey what a listener of the time could have expected to hear even with the best available equipment. While it's undeniably thrilling to be able to glean musical information that the original discs never yielded to their intended audience (here including hints of the instruments' woody resonances), perhaps that modern advantage not only falsifies the sound of the time but is unfair, both for comparison with contemporary competition and to the artists, who were required to conform their performances to accommodate the mechanical criteria (e.g., having to compress dynamics and skew balances for the acoustical horn) and at the same time were able to take cover within a safety zone of the technology's inherent limits to conceal some of the inevitable blemishes in their work that radical restoration reveals. But even after mentally tuning out Pristine's sonic enhancements, the Dyke Quartet still comes across as remarkably modern, except for ample portamento – well-balanced and precise, with minimal vibrato or tempo fluctuation. Yet they also seem unduly rushed, mechanical and cold both in the first movement where they largely ignore the score specification of rubato and in the finale where it indicates passion. Even so, the sharp articulation of their playing tends to convey a contagious enthusiasm and the third movement is considerably more expressive, as the score specifies there.

The other acoustical set seems as elusive as it would be compelling to hear.

The World Records playback contraption |

![]() The vast majority of string quartets are formed upon the musicians' own initiative, or perhaps through the encouragement of shared mentors.

The vast majority of string quartets are formed upon the musicians' own initiative, or perhaps through the encouragement of shared mentors.

The Virtuoso Quartet |

It seems fair to assume from his focus on "vividness and sonority" that the reviewer, at the very dawn of the electrical era, was awed by the greater warmth, more prominent overtones, wider dynamics and general sonic improvement over the acoustical method – and indeed (at least in a digital transfer) the pizzicati really "pop" and the lines emerge more distinctly than in the predecessors. Even aside from technological allure the ensemble is tight, accents sharp, dynamics wide, and the overall impression quite modern, with light vibrato and only occasional portamento.

It seems fair to assume from his focus on "vividness and sonority" that the reviewer, at the very dawn of the electrical era, was awed by the greater warmth, more prominent overtones, wider dynamics and general sonic improvement over the acoustical method – and indeed (at least in a digital transfer) the pizzicati really "pop" and the lines emerge more distinctly than in the predecessors. Even aside from technological allure the ensemble is tight, accents sharp, dynamics wide, and the overall impression quite modern, with light vibrato and only occasional portamento.

In the meantime, excerpts continued – three or four sides (the catalog numbering is confusing; the last could have been a retake) in 1925 by the New York String Quartet for Brunswick (labelled "Andantino," "Intermezzo," "Romance" and "1st Movement") and another Andante in 1927 by the Hungarian Roth Quartet on Odeon. Indeed, the latter seems especially curious – why so many Andantes when the second movement would have seemed a more propitious choice – it's upbeat and catchy, its pizzicato texture was well-suited to the acoustical pickup, and it fit easily on a single side rather than requiring abbreviation. Indeed, in its April 1925 review of the Dyke and Abkov complete recordings (praising the former as "a very fine performance" and the recording as "splendid"), the Gramophone remarked: "The Andante is one of the most popular of all snippets but the rest of the quartet is not a whit less attractive." In any event, the Roth Andante was issued complete on two sides and boasts beautifully expressive shaping of both individual phrases and the overall architecture.

Until 1928 recordings of this most quintessentially French work had been dominated by the British, exemplifying Tully Potter's assertion that their unshowy, blended style was especially conducive to string quartet playing.  Relief finally arrived across "The Pond" from the Léner and Capet Quartets in 1928, to be joined by the Calvet in 1931 (all, oddly, on Columbia) and the Pro Arte on HMV in 1933.

Relief finally arrived across "The Pond" from the Léner and Capet Quartets in 1928, to be joined by the Calvet in 1931 (all, oddly, on Columbia) and the Pro Arte on HMV in 1933.

In a 1935 book on the technique of string quartet playing, Jeno Léner stressed the need to surmount most difficulties by attending to accents,

The Lener Quartet |

In an era when permanent chamber groups (as opposed to moonlighting orchestral musicians) were still quite rare,

The Capet Quartet |

The Calvet Quartet's 1931 Debussy Quartet was its phonographic debut

The Calvet Quartet |

The next recording came in 1933 from the Belgian Pro Arte Quartet,

The Pro Arte Quartet |

The penultimate pre-LP recording was a 1940 Columbia set from the Budapest Quartet,

The Budapest Quartet |

The Quartetto Italiano began in 1942 when four students intensively studied the Debussy Quartet, which remained their cornerstone as they thrived through 1980 with only a single personnel replacement. Their 1966 Philips pairing of the Debussy and Ravel quartets

The Quartetto Italiano |

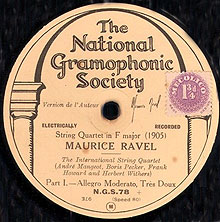

![]() The recording history of the Ravel Quartet began similarly to the Debussy with isolated movements (some abridged) from the London Quartet (1917 – the first movement on two sides; third and fourth each on one), Philharmonic Quartet (1918 – third and fourth movements on three sides) and Catterall Quartet (1922-3 – the first movement on one side – five takes, but none issued). But while the first complete recording had to await the electrical era, it boasted a weighty pedigree that none of the Debussy sets could offer – supervised and authorized by the composer himself!

The recording history of the Ravel Quartet began similarly to the Debussy with isolated movements (some abridged) from the London Quartet (1917 – the first movement on two sides; third and fourth each on one), Philharmonic Quartet (1918 – third and fourth movements on three sides) and Catterall Quartet (1922-3 – the first movement on one side – five takes, but none issued). But while the first complete recording had to await the electrical era, it boasted a weighty pedigree that none of the Debussy sets could offer – supervised and authorized by the composer himself!

André Mangeot, a violinist friend of Ravel, had attempted a recording with his International Quartet but was dissatisfied with its degree of clarity and transparency.  As he recounted in a September 1927 Gramophone article, he took test pressings of a second attempt to Ravel, who was visiting London: "As the records were played he marked [the score] whenever there was an effect or a tempo that he wanted altered. … He is most precise – he knows exactly what he wants – how, in his mind, every bar of his Quartet ought to sound. So, armed with such final authority, we had another recording at the studio and my colleagues and I rehearsed hard for it over those little details." Presented with the results, Ravel provided Mangeot with a letter reading: "I have just heard the discs … . I am completely satisfied as much with the sonority as with the tempi and the nuances." He further said to Mangeot: "It will constitute a real document for posterity to consult, and through gramophone records composers can now say definitively how they meant the works to be performed." When issued by the National Gramophonic Society, each label bore the legend "Version de l'Auteur" and a facsimile of Ravel's signature.

As he recounted in a September 1927 Gramophone article, he took test pressings of a second attempt to Ravel, who was visiting London: "As the records were played he marked [the score] whenever there was an effect or a tempo that he wanted altered. … He is most precise – he knows exactly what he wants – how, in his mind, every bar of his Quartet ought to sound. So, armed with such final authority, we had another recording at the studio and my colleagues and I rehearsed hard for it over those little details." Presented with the results, Ravel provided Mangeot with a letter reading: "I have just heard the discs … . I am completely satisfied as much with the sonority as with the tempi and the nuances." He further said to Mangeot: "It will constitute a real document for posterity to consult, and through gramophone records composers can now say definitively how they meant the works to be performed." When issued by the National Gramophonic Society, each label bore the legend "Version de l'Auteur" and a facsimile of Ravel's signature.

Heard today, this purportedly definitive author's version indeed is revelatory. While it closely follows the detailed dynamic, accent and tempo markings in the score, it presents many relatively minor adjustments and expressive refinements. Of particular interest is the abundant portamento, which Ravel apparently approved, if not demanded, and which adds to a sensation of fluidity, plus strong dynamics that convey an undertone of anxiety and yearning. The recording itself does the performance few favors (at least not in the extremely noisy "straight" transfer on a Music and Arts CD), distorting some balances (e.g., the pizzicato accompaniment drowning out the bowed melody in the second movement) and obscuring much of the delicate filigree figures that enliven the third and fourth movements. Even so, this version comes across as a vivid, committed reading that belies any notion that the composer envisioned his Quartet as comforting amusement (but this assumes that his outlook hadn't evolved significantly over the quarter-century since composition).

Complementing the International reading of the Quartet for stylistic guidance

Ravel and "Septet" ensemble |

Ravel purportedly supervised a second recording of his Quartet

The Galimir Quartet |

In light of its limited circulation,

The Krettly Quartet |

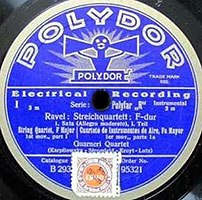

A forebear of the Galimir approach (and most of those that would follow), they indulge few of the "old school" techniques and instead present the music with little inflection, careful balances and much restraint even though, if we credit the International Quartet with documenting Ravel's aim, he would have welcomed an injection of more expression and even some individuality to flesh out the specifications of the printed score. (For the sake of completeness we should note that amid the abundance of full recordings came one more disc of an isolated movement by the Guarneri Quartet (Polydor, 1929) – not the celebrated American ensemble formed at Marlboro in 1964 that compiled a wide-ranging discography during its 45-year tenure, but a German one active from 1925-1934 that conveys the first movement well, if without much of the warmth, nuance and sheer personality in the 1974 RCA LP of its later namesake.)

A forebear of the Galimir approach (and most of those that would follow), they indulge few of the "old school" techniques and instead present the music with little inflection, careful balances and much restraint even though, if we credit the International Quartet with documenting Ravel's aim, he would have welcomed an injection of more expression and even some individuality to flesh out the specifications of the printed score. (For the sake of completeness we should note that amid the abundance of full recordings came one more disc of an isolated movement by the Guarneri Quartet (Polydor, 1929) – not the celebrated American ensemble formed at Marlboro in 1964 that compiled a wide-ranging discography during its 45-year tenure, but a German one active from 1925-1934 that conveys the first movement well, if without much of the warmth, nuance and sheer personality in the 1974 RCA LP of its later namesake.)

The LP and CD eras brought a bounty of dozens more recordings of both Quartets (often paired), but their stylistic models can be traced back to those we've noted through the 1940s, so this seems an apt place to close our survey. There are plenty of online reviews to guide those who insist upon hi-fi sound, stereo or digital formats, although I would caution that ignoring the pioneers, as most reviewers tend to do nowadays, forfeits a vast and crucial realm of seminal style and compelling artistry.

|

![]() As usual in these articles, I take full credit/blame for the musical judgments but have undertaken no original factual research and have relied upon the following edited and/or peer-reviewed (and thus seemingly credible) sources for the quotations and references:

As usual in these articles, I take full credit/blame for the musical judgments but have undertaken no original factual research and have relied upon the following edited and/or peer-reviewed (and thus seemingly credible) sources for the quotations and references:

- Generally:

- Berger, Melvin: Guide to Chamber Music (Doubleday, 1990)

- Grout, Donald Jay: A History of Western Music (Norton, 1973)

- Keller, James M.: Chamber Music – A Listener's Guide (Oxford, 2010)

- Shibatani, Naomi: Contrasting Debussy and Ravel – A Stylistic Analysis of Selected Piano Works and Ondine (Thesis, Rice University, 2008)

- On Debussy:

- Applebaum, Edward: notes to the Fine Arts Quartet CD (Concert-Disc 253, c. 1962)

- Brockway, Wallace and Herbert Weinstock: Men of Music (Simon & Schuster, 1958)

- Goodall, Howard: The Story of Music from Babylon to the Beatles – How Music Has Shaped Civilization (Pegasus, 2013)

- Howat, Roy: "Debussy, (Achille) Claude" in New Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Stanley Sadie, ed., Oxford, 2001)

- Lang, Paul Henry: Music in Western Civilization (Norton, 1941)

- Lockspeiser, Edward: Debussy – His Life and Mind (Cassell, 1962)

- Mellers, Willfred: Man and His Music – Romanticism and the 20th Century (Shocken, 1962)

- Orledge, Robert: "Debussy the Man" in The Cambridge Guide to Debussy (Simon Trazise, ed., Cambridge University, 2003)

- Salzman, Eric: Twentieth Century Music – An Introduction (Prentice-Hall, 1967)

- Scholes, Percy: Oxford Companion to Music (Oxford, 1955)

- Schonberg, Harold: The Great Pianists (Simon & Schuster, 1963)

- Tubeuf, André: notes to Capet Quartet LP reissue (EMI Références 2 C 051-16419)

- Vallas, Leon: Claude Debussy – His Life and Works (tr.: Marie and Grace O'Brien; Oxford University, 1933; Dover reprint, 1973)

- On Ravel:

- Jacobson, Bernard: notes to the Quartetto Italiano LP (Philips 835 361 AY, 1966)

- Kelly, Barbara L.: "Ravel (Joseph) Maurice" in New Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Stanley Sadie, ed., Oxford, 2001)

- Orenstein, Arbie: Ravel – Man and Musician (Columbia University Press, 1975)

- Roland-Manuel: Maurice Ravel (tr.: Cynthia Jolly; Dennis Dobson, 1947; Dover reprint, 1972)

- On the Quartets:

- Darwin, Chris: Program Note

- Ferchault, Guy: notes to the LaSalle Quartet LP (DG 2530 235, 1972)

- Griffiths, Paul: The String Quartet – A History (Thames & Hudson, 1983)

- Hodier, André: Since Debussy (Grove Press, 1961)

- Holbreich, Harry: notes to Loewenguth Quartet LP (Vox GBY 12020, 1962)

- Rosenfeld, Paul: Musical Portraits – Interpretations of 20 Modern Composers (Harcourt, Brace & Howe, 1920)

- Simeone, Nigel: notes to the Eroica Quartet download (Reconus RES 10107, 2012)

- Sutarjo, Jane Ade: Debussy and Ravel's String Quartets – An Analysis (Iceland Academy of the Arts, Spring 2011)

- On the recordings:

- AHRC Research Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music

- Forman, Frank: Acoustic Chamber Music Sets (1899–1926): A Discography (self-published, 2003)

- Malloch, William: notes to Maurice Ravel: Ses Amis et Ses Interprètes (Music and Arts CD 703, 1992)

- November, Nancy: "Commonality and Diversity in Recordings of Beethoven's Middle-Period String Quartets" (Performance Practice Review, Vol, 15, No. 1, 2010)

- Potter, Tully: "The Concert Explosion and the Age of Recording" in The Cambridge Guide to the String Quartet (Robin Stowell, ed., Cambridge, 2003)

And … I'm deeply grateful for the Petrucci Music Library – both Quartets are among its nearly half-million (!) public domain scores available free on line – and to several collectors (whose privacy I'll respect) who generously shared their knowledge and audio files of nearly all the essential historical recordings mentioned here.

![]()

Copyright 2018 by Peter Gutmann

copyright © 1998–2018 by Peter Gutmann. All rights reserved.